The issue of Guyana as a low trust society (sometimes construed to be a lack of confidence) has been mentioned in discussions at the University of Guyana, on social media and in the press. With respect to the emerging oil industry, some expressed lack of trust in the government’s handling of related matters, whereas others have bemoaned this state of affairs. What is sometimes missing from these discussions is clear recognition of the reasons for the current state of trust and what is required for building institutional trust.

Low institutional trust (and even distrust) results from failure of the institutions (government) to perform competently and consistently and from the extent to which citizens have been disappointed and even abused by the institutions and their representatives (for example, Chand & Chu, 2006). Guyana lacks a consolidated democracy and its institutions are generally subordinated under the executive that in general still operates under the doctrine of party paramountcy and remain susceptible to the shocks of political vagaries. The rampant corruption that plagues society (See TI’s Corruption Perception Index), itself the result of institutional failures, has also undermined the performance of institutions. This combination has rendered Guyanese institutions chronically weak, incompe-tent and demoralised, leading to enduring skepticism about the motives behind and the beneficiaries of

institutional actions (Chand & Chu, 2006). Essentially, low institutional trust would mean that institutions have not proven themselves to be trustworthy. Building trust in institutions should, therefore, be a key goal of the executive if it intends to move Guyana forward.

Institutional Failures with Trust Implications

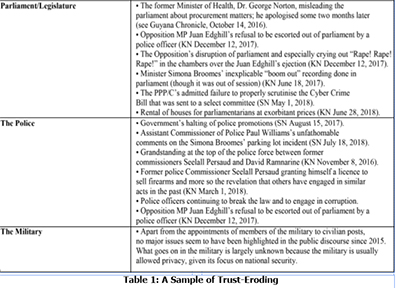

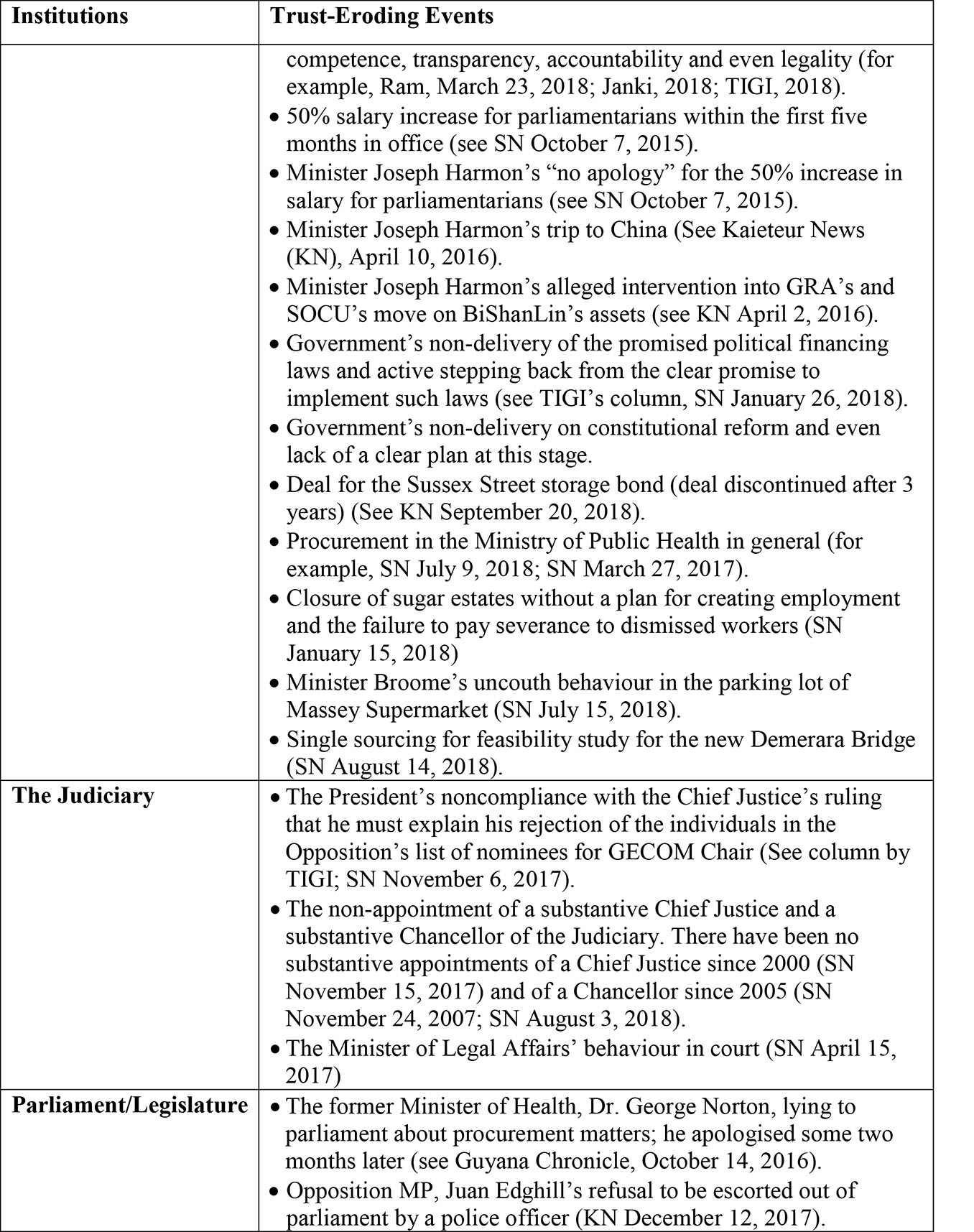

The following table highlights some events that would likely have eroded trust in important institutions that are usually included in measurements of institutional trust.

It is important to note that Table 1 1) does not present an exhaustive list of trust eroding events that took place since 2015; 2) identifies only the institutions that are popularly cited in the institutional trust literature. Several others including local government are relevant to Guyana but are not discussed in this column; and 3) does not seek to identify occurrences that would likely have impacted positively on trust. This does not mean that there were no positive events. A clear counterexample is the release of the contract with ExxonMobil (see Department of Public Information). However, it is much easier to erode than to build institutional trust and the table, therefore, focuses on occurrences (though not exhaustively) that should have been avoided.

Trust and the Petroleum Industry:

A More Detailed Look

Guyana entered a new petroleum contract with ExxonMobil in 2016 away from the view of citizens. This mode of operation is not unlike what occurred previously when the PPP/C was in government. The significance, however, lies in the reality that the essence of the APNU+AFC’s mandate was to rebuild institutional trust. Not only was it expected to stop and sanction corruption, but also to inaugurate a mode of operation that would transform Guyana.

More than a year after the signing of the new contract, receipt of a US$18 million signing bonus was confirmed by a leaked letter (see SN December 8, 2018). It was also revealed that the money was illegally placed outside of the Consolidated Fund and away from the control of parliament; not corrected to date (SN March 30, 2018). In this saga, the Minister of Finance had denied the existence of a signing bonus, while other ministers evaded the question (KN November 23, 2017) and the Minister of Natural Resources Raphael Trotman, had (in a May 2, 2017 letter to TIGI) expressed commitment to consultation prior to issuing a production agreement, when, in fact, the agreement was signed in the previous year.

The 2016 contract with ExxonMobil was eventually released in an unprecedented and laudable action by the Government. This action cannot be denied but it does not compensate for the initial secrecy, especially given the uncovering of provisions and lack thereof in the contract with ExxonMobil that have been identified as illegal (Janki, 2018; KN March 30, 2018; Ram, 2018; TIGI, April 30, 2018) and as overly favourable to ExxonMobil (see for example, KN April 10, 2018; KN March 20, 2018).

The government of Guyana has expressed its determination to move ahead, despite calls for renegotiation and for fixing the illegalities. It is apparent, therefore, that unless citizens organise to force the changes they desire, successful litigation is the last chance to effect any changes and to secure a better deal for Guyana (SN February 23, 2018). By the time the contract was released, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Carl Greenidge, had appeared to attempt to direct the focus of the press (particularly that of Kaieteur News) away from ExxonMobil (see KN December 15, 2017) and a ministerial trip to Texas to engage with ExxonMobil had been paid by ExxonMobil (see SN, August 30, 2017). Much of what has occurred in the emerging petroleum industry to date has eroded rather than built trust in the executive’s handling of the industry.

Institutional Trust in Wider Society

There have also been shocks to institutional trust outside of the oil industry since 2015.

Without attempting to repeat everything presented in the table, we record a few observations about what is already listed there. Several shocks relate to trust in the executive but other institutions were not spared.

The APNU+AFC government began with a 50% increase in the salaries of parliamentarians within the first five months in office (SN October 7, 2015). This was widely criticised as a betrayal of the people, but the act itself was overshadowed by the Minister of State’s pronouncement that he had no apologies to make for it (SN October 7, 2015). His apology, which followed six weeks of defiance (see column by Kissoon, April 8, 2016), seemed more calculated than contrite and this singular reaction by this most senior and influential government official, who oversees the Ministry of the Presidency, set the tone for trust in government from October 6, 2015 to date.

The President himself promised campaign financing laws and reiterated this commitment after winning the 2015 elections but has not delivered to date (See Guyana Chronicle April 9, 2016; see also column by David Hinds, Guyana Chronicle, January 27, 2018). This issue had all but dropped from public discourse with help from some sitting ministers of government (see TIGI’s column, SN January 26, 2018), but a more recent expression of intent to pursue political financing legislation by Minister Khemraj Ramjattan offers some hope (SN May 14, 2018) even though the next round of local government elections will take place in November, 2018 without political financing laws. The PPP/C did not implement political financing laws in its 23 years in government and has not advanced the cause since it has been in opposition. It is difficult to trust a government or political party that either actively or passively frustrates efforts to get political financing legislation enacted.

The government’s handling of constitutional reform has also not inspired trust. Constitutional reform was expected to be high on the legislative agenda but, to date, tangible steps and a clear timetable are not evident. It does appear that having tasted the protection of the constitution, the executive has lost its appetite for positive change.

The recent uncouth behaviour of Minister Broomes in the parking lot of the Massy Supermarket at Providence provides a glimpse into the how the executive (or some thereof) can abuse the power entrusted to them. From all indications, Minister Broomes was not aware that one of the security guards was not legally allowed to carry a firearm as it was subsequently discovered. This means that the actions of Minister Broomes with the consequence that security personnel were detained and locked up by the police for 16 hours (SN July 28, 2018) could have been directed at anyone who dared to stand in her way. This incident is also an evaluation of the updated Code of Conduct for public officers. It testifies of the impotence of the Code, which was already recognised by civil society (see for example KN April 24, 2017; Guyana Human Rights Association, April 19, 2017).

The judiciary was not spared from shocks to trust. The President’s rejection of the court ruling that he must justify his rejection of the individuals in the Opposition Leader’s lists of nominees for the GECOM Chair was a rather unfortunate development (See column by TIGI; SN November 6, 2017) which undermined the authority of the court. President Granger essentially tossed a court decision over his shoulder in the clear view of all. The eventual appointment of a GECOM Chair outside of the Opposi-tion Leader’s list furthermore eroded trust in GECOM.

Both the government’s MPs and those of the Opposi-tion have dealt significant blows to trust in parliament and the legislature since 2015. This ranges from Minister Broomes’ inexplicable “boom out” recording to the PPP/C’s MPs’ disruption and shouting of “Rape! Rape! Rape!” as they prevented a police officer from executing his job.

Building Institutional Trust

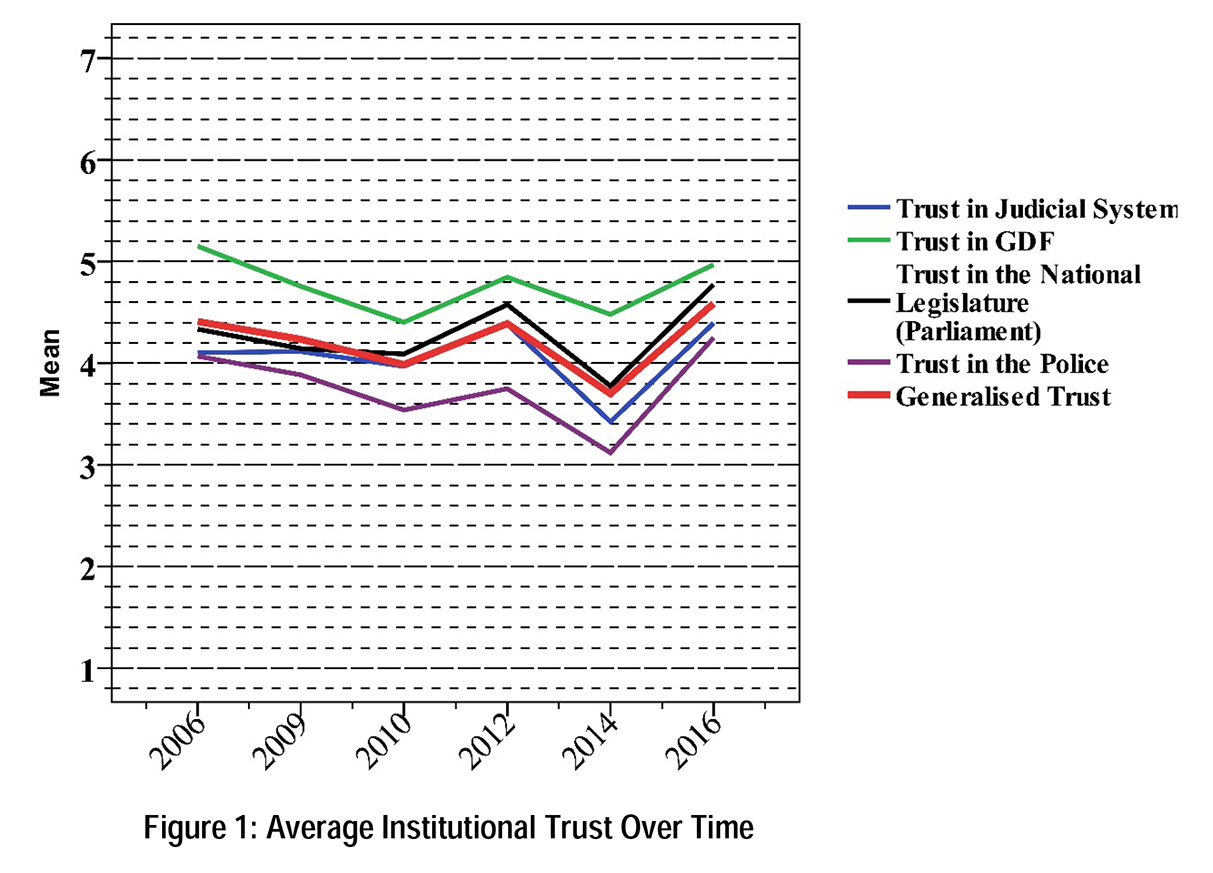

The available LAPOP data (up to 2016, see Figure 1) indicate that following the trust nosedive in 2014, there was a recovery by 2016. In that time, there was a change in government. It is likely that a trust catastrophe was averted by the mid-2015 change in government and this resurgence to slightly higher generalised institutional trust than the pre-2014 levels resulted from the optimism inspired by the APNU+AFC coalition as it took the reins of government amidst promises to sanction corruption and elevate the level of transparency and accountability of government and its institutions. Never-theless, in spite of the 2016 normalisation (if slightly better; Generalised trust rose to 4.6 on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (a lot)), the level of institutional trust is still low overall and it is unlikely that institutional trust has been built since then given the regularity of scandals, including actions that have been regarded as corrupt (see the sample list in the table above).

Average Institutional Trust over Time

In its first three years in government, the APNU+AFC coalition has demonstrated wavering commitment to building institutional trust and to dealing effectively with shocks to the system resulting from its own performance in government. Building institutional trust would necessitate enduring commitment to transparency and accountability and openness to queries from citizens beyond convenience. It also requires commitment to strengthening competence and performing competently. When government and its institutions have demonstrated trustworthiness over time, citizens will become more willing to allow them to function without a detailed grilling at every turn. Trust cannot be willed or legislated into existence and people cannot be embarrassed into trusting institutions.

To build trust, the institutions must demonstrate trustworthiness beyond the ebb and flow expected in response to changes in government. We have seen an important development in the petroleum industry (discussed above). We also noticed that the government has launched a website to provide information on scholarships. This is an issue on which TIGI had commented previously (see SN April 7, 2018) and it is hoped that lists of awardees will be published.

However, what we have experienced is in large part disregard (and sometimes disdain) for those who question and often (though not always) neglect of the responsibility to remain open, transparent and accountable. It is unacceptable, for example, that the President, who has to lead the process of rebuilding institutional trust, has held only three press conferences in three years (KN August 30, 2018). One cannot build trust in government in this way. The government needs to consolidate its effort at building trust and to do so it would be necessary to address problems that arise decisively and to put into action its continued rhetoric of being transparent and accountable to the people. In this regard, the manner in which the ongoing wage dispute with the Guyana Teachers’ Union is handled is yet another matter that will make an important contribution to evaluations of trust in government and its institutions.