THE DECLARATION

AGAINST CORRUPTION

I will not pay bribes

I will not seek bribes

I will work with others to campaign against corruption

I will speak out against corruption and report on abuse

I will only support candidates for public office

who say no to corruption and demonstrate transparency, integrity and accountability

The above declaration has been developed by Transparency International (TI), the international watchdog organisation, headquartered in Germany, whose vision is for a world that is free of corruption. Through chapters in more than 100 countries, TI works together with governments, businesses and citizens to stop the abuse of power, bribery and secret deals. The Declaration is “consistent with and supportive of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the United Nations Convention against Corruption. It is also consistent with Transparency International’s core values: Transparency, Accountability, Integrity, Solidarity, Courage, Justice, Democracy.” Accountability Watch urges all those who are committed to fighting corruption to join forces with the 23,161 persons who have signed the Declaration so far.

Over in New Zealand, the government has placed a new cap on drilling for oil and gas in its waters as part of its efforts to combat climate change. Accordingly, it will no longer be granting any new offshore oil and gas exploration permits. According to the Prime Minister, “This is another step on our transition away from fossil fuels and towards a carbon neutral economy”. And in Brooklyn, New York, a prominent gay rights lawyer, David Buckel, committed suicide by setting himself on fire in protest against the use of fossil fuels. He left a note which reads “Pollution ravages our planet, oozing inhabitability via air, soil, water and weather. Most humans on the planet now breathe air made unhealthy by fossil fuels, and many die early deaths as a result — my early death by fossil fuel reflects what we are doing to ourselves”.

Some final thoughts on the work of the PAC

Last week, we concluded our review of the report of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) on the public accounts for the years 2012-2014. The PAC, however, does not examine the accounts of public corporations and other State-owned/controlled entities nor the accounts of municipalities and Neighbourhood Democratic Councils (NDCs). The Constitution defines public accounts to include the accounts of: (i) all central and local government bodies and entities; (ii) all bodies and entities in which the State has controlling interest; and (iii) all projects funded by way of loans or grants by a foreign State or organisation.

With the PAC’s focusing almost exclusively on central government activities using the Auditor General’s report as its frame of reference, a greater portion of what constitutes the public accounts escapes its scrutiny. Most of these non-central government bodies receive subventions from the National Budget to meet the cost of operations as well as capital funding for infrastructure works. To compound matters, several such entities, including the Georgetown City Council, other municipalities and NDCs, continue to be significantly in arrears in having their accounts audited. Indeed, a number of NDCs have not had audited accounts since they were established in 1993.

It is inconsistent for the PAC to grill Heads of Budget Agency even in some cases for minor infractions of the financial and procurement laws and related regulations while those responsible for the accounts of the other entities constituting the public accounts escape similar grilling. These entities are perhaps in greater need of scrutiny as the results of the forensic audits would bear out. The PAC could also learn from the experience of its Bermuda counterpart which has been more proactive in examining current issues rather than focusing almost exclusively on the Auditor General’s reports.

Corruption and the VIII Summit of the Americas

At the recently concluded meeting of the VIII Summit of the Americas in Lima, Peru, Heads of Government approved of the Lima Commitment “Democratic Governance against Corruption”. They underscored “that the prevention of and fight against corruption are fundamental to strengthening democracy and the rule of law in our States, and that corruption weakens democratic governance and citizens’ trust in institutions, in addition to having a negative impact on the effective enjoyment of human rights and the sustainable development of the peoples of our Hemisphere as well as other regions of the world”. In announcing the theme for the meeting in June last year, the OAS Secretary-General stated that “The future of the region stands at a critical juncture because of the threats to democratic governance, whether from the corruption that is eating away at institutions from within in several countries, or because they have been turned into empty shells by an authoritarian regime that curtails the individual guarantees and freedoms of citizens, as is currently the case in Venezuela”.

Corruption in perspective

TI defines corruption as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain. It can be classified as grand, petty and political, depending on the amounts of money lost and the sector where it occurs. Corruption corrodes the fabric of society. It undermines people’s trust in political and economic systems, institutions and leaders. It can cost people their freedom, health, money – and sometimes their lives.” TI considers that grand corruption consists of acts committed at a high level of government that distort policies or the central functioning of the State, enabling leaders to benefit at the expense of the public good. On the other hand, petty corruption refers to everyday abuse of entrusted power by low- and mid-level public officials in their interactions with ordinary citizens, who often are trying to access basic goods or services in places like hospitals, schools, police departments and other agencies. Political corruption is a manipulation of policies, institutions and rules of procedure in the allocation of resources and financing by political decision makers, who abuse their position to sustain their power, status and wealth.

The implications of corruption are enormous and wide-ranging. Corruption undermines democracy and the rule of law, and causes society to degenerate. It benefits the rich and powerful at the expense of the poor, the unemployed youth, and the vulnerable and less fortunate, including women and children, the sick and the elderly. Corruption behaviour by officials holding high public office results in scarce public resources being diverted away and not made available to attend to the basic needs of citizens. It is cancerous and destroys the moral and social fabric of society. Corruption is an immoral and criminal act that deprives citizens of their fundamental human rights.

TI asserts that “Corrupt politicians invest scarce public resources in projects that will line their pockets rather than benefit communities, and prioritise high-profile projects such as dams, power plants, pipelines and refineries over less spectacular but more urgent infrastructure projects such as schools, hospitals and roads. Corruption also hinders the development of fair market structures and distorts competition, which in turn deters investment. Corruption corrodes the social fabric of society. It undermines people’s trust in the political system, in its institutions and its leadership… the lack of, or non-enforcement of, environmental regulations and legislation means that precious natural resources are carelessly exploited, and entire ecological systems are ravaged. From mining, to logging, to carbon offsets, companies across the globe continue to pay bribes in return for unrestricted destruction”.

Corruption Perceptions Index

Given the opaque nature of corruption, it is not possible to measure actual levels of corruption that exists in a society. It is mainly for this reason that TI launched its annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) in 1995. Developed by Prof. Johann Landsdorff of the University of Passau in Germany, the CPI is computed based on annual surveys carried out of the views of knowledgeable persons and business executives of the extent to which corruption is perceived to exist in a country.

The surveys are undertaken by independent and reputable institutions, such as the Economic Intelligence Unit, World Bank, the World Economic Forum, African Development Bank and Varieties of Democracy. For example, 13 data sources from 12 institutions were used in computing the CPI 2017. For a country/territory to be included in the CPI, there must be a minimum of three data sources. The results of the surveys have correlated well over the years and provide a fair measure of actual levels of corruption in a country.

CPI 2017 Results

On 21 February 2018, Transparency International released the CPI for 2017. Of the 180 countries/territories surveyed, 2/3 scored below 50 out of 100, with average score of 43. The results are similar to those of previous years, indicating that the majority of countries have made little or no progress in their fight against corruption. The top performers were New Zealand (89), Denmark (88), Finland (85) and Norway (85) while at the bottom of the table were Somalia (9), South Sudan (12) Syria (14) and Afghanistan (15). TI indicated that further analysis of the results shows that countries with the least protection for press and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) also tend to have the worst rates of corruption. Every week at least one journalist is killed in a country that is highly corrupt, and in the last six years, more than 9 out of 10 who were killed were from countries that scored 45 or less on the CPI.

According to the Chair of TI, “CPI results correlate not only with the attacks on press freedom and the reduction of space for civil society organisations. In fact, what is at stake is the very essence of democracy and freedom”. TI’s Managing Director echoed a similar sentiment by asserting that “No activist or reporter should have to fear for their lives when speaking out against corruption. Given current crackdowns on both civil society and the media worldwide, we need to do more to protect those who speak up.”

TI has made the following key recommendations:

(a) Governments and businesses must do more to encourage free speech, independent media, political dissent and an open and engaged civil society;

(b) Governments should minimise regulations on media, including traditional and new media, and ensure that journalists can work without fear of repression or violence. In addition, international donors should consider press freedom relevant to development aid or access to international organisations;

(c) Civil society and governments should promote laws that focus on access to information. This access helps enhance transparency and accountability while reducing opportunities for corruption. It is important, however, for governments to not only invest in an appropriate legal framework for such laws, but also commit to their implementation;

(d) Activists and governments should take advantage of the momentum generated by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to advocate and push for reforms at the national and global level. Specifically, governments must ensure access to information and the protection of fundamental freedoms and align these to international agreements and best practices; and

(e) Governments and businesses should proactively disclose relevant public interest information in open data formats. Proactive disclosure of relevant data, including government budgets, company ownership, public procurement and political party finances allows journalists, civil society and affected communities to identify patterns of corrupt conduct more efficiently.

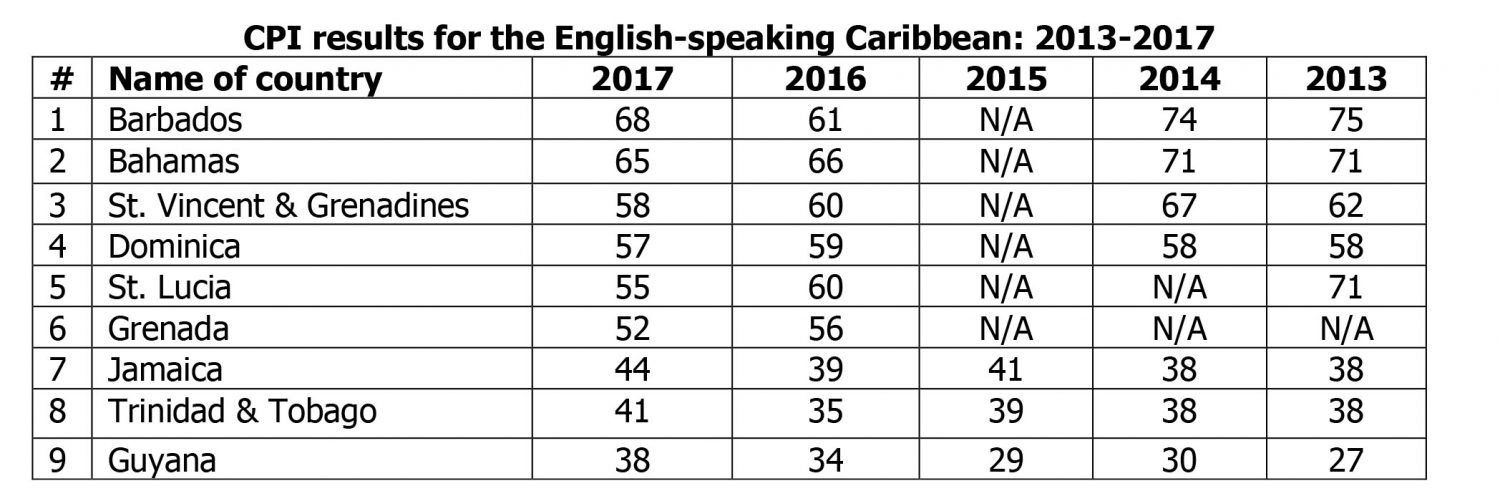

Closer home, the English-speaking Caribbean countries have recorded a mixed performance in 2017, compared with 2016. Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad & Tobago and Guyana have shown improvements by on average 5.5 points while the remaining five countries declined by on average 2.8 points, as shown in the table below:

As can be noted, Guyana remains at the bottom of the table of English-speaking Caribbean countries. Significantly more and sustained efforts therefore need to be made to reduce the extent to which corruption is perceived to exist in the Guyanese society.