I will not pay bribes.

I will not seek bribes.

I will work with others to campaign against corruption.

I will speak out against corruption and report on abuse.

I will only support candidates for public office who say no to corruption and demonstrate transparency, integrity, and accountability.

Petition drafted by Transparency International

Former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan and his wife have been jailed for 14 years for illegally profiting from the receipt of state gifts, including a jewelry set from the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia. They have also been fined some US$5.3 million. Two days earlier, the former Pakistani test cricket captain was sentenced to ten years in prison for leaking classified state documents. He is accused of not returning a diplomatic document after he was removed from the office of Prime Minister in 2022. Khan has also been banned from future political work as well as from holding public office for ten years. He has insisted that the numerous cases against him are politically motivated. See https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-68150959; and Imran Khan sentenced to ten years in prison by Pakistan court – ESPN.

Italy’s public debt is more than US$3 trillion. To reduce the country’s debt burden, Prime Minister Meloni has announced the sale of up to 13 percent of the government’s stake in its postal service which has been described as Italy’s “crown jewel” because of the huge profits it has been making through its insurance and banking operations. Also, up for sale are the rail company Ferrovie dello Stato and the energy giant Eni. The plan is to raise US$21.6 billion, which according to analysts is unlikely to have any impact on Italy’s public debt. See: https://uk.finance.yahoo.com/news/italy-plans-sell-around-13-161555539.html.

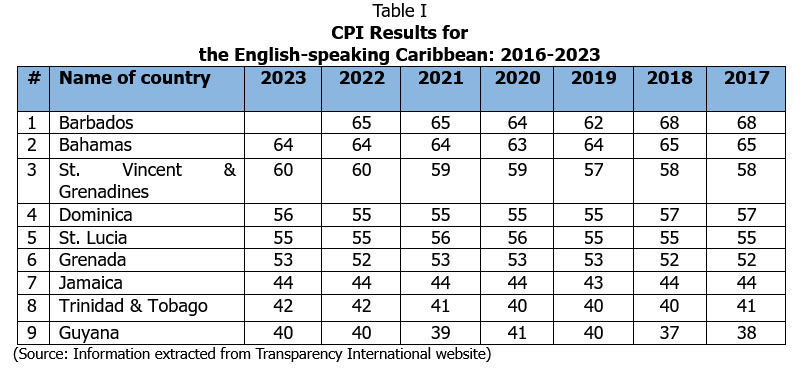

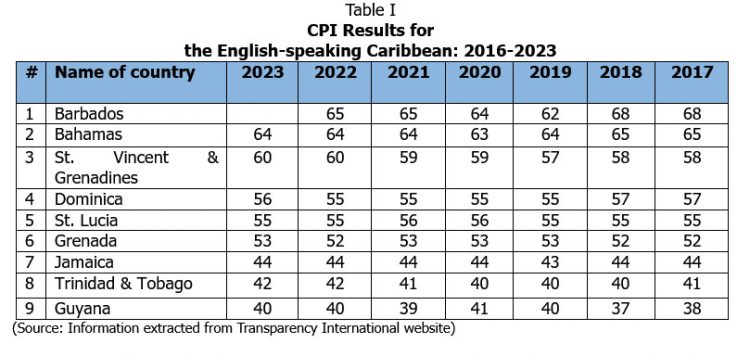

Last Tuesday, Transparency International (TI) released its 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) which shows that after 20 years of the adoption of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) progress remains limited. In particular, from among the 180 countries surveyed, 68 percent scored less than 50 out of 100. TI has examined the relationship between corruption and justice and found that declining justice and rule of law worldwide is creating widespread impunity for corruption. Corruption is also contributing to the erosion of justice in relation to both authoritarian and democratic governments:

Leaders are depriving justice institutions of the funding and powers they need to uphold the law effectively. Politicians are also interfering with them to prevent consistent, fair enforcement and application of the law and to reduce limits on government powers. Ultimately, this is creating widespread impunity for corruption across the globe.

Guyana’s score on the 2023 CPI remained at 40 out of 100, the lowest in the English-speaking Caribbean. This was despite the various anti-corruption mechanisms in place over the years. Table I, taken from last week’s article and updated to include the results for 2023, shows the CPI results for the English-speaking Caribbean.

(a) Creation of the Guyana Revenue Authority in 1996

(b) Guyana being a signatory to the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption (IACAC) in 1997.

(c) Passing of the Integrity Commission Act in 1997.

(d) 2001 constitutional amendments for the establishment of the Public Procurement Commission and to secure the independence of the Audit Office of Guyana.

(e) Enactment of the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act 2003.

(f) Enactment of the Procurement Act 2003.

(g) Enactment of the Audit Act 2004.

(h) Ratification of the UNCAC in 2005.

(i) Passing of the Anti-Money Laundering Act in 2009 and its subsequent amendments.

(j) Establishment of the now disbanded State Assets Recovery Agency in 2015.

(k) Establishment of Guyana’s Extractive Industries Transparency

Initiative in 2017.

(l) Enactment of the Protected Disclosures Act 2018.

(m) Enactment of the Natural Resource Fund Act 2021.

Creation of the Revenue Authority

The Revenue Authority was established in 1996 as a corporate entity with a governing board. The operations of the two departments under the Ministry of Finance – the Inland Revenue Department and the Customs Department – have been transferred to this entity, the objective being to provide the GRA with greater autonomy and flexibility, free of direct ministerial involvement, as the tax assessment and collection agency of the State. However, the majority of board members have a direct reporting relationship with the Minister in their substantive positions in government. Additionally, it is unclear whether the GRA is involved in the conduct of “life-style” audits and arbitrary assessments to ensure the completeness and accuracy of tax returns of individuals, unincorporated entities and companies, considering the extent of unexplained wealth that is being flaunted in front of our very eyes.

Guyana a signatory to the IACAC

Guyana is a signatory to the IACAC which came into effect in March 1997. It also ratified the Convention in December 2000. The main objective of the IACAC is to promote and strengthen the development of mechanisms needed to prevent, detect, punish, and eradicate corruption. Preventive measures include creating, maintaining, and strengthening standards of conduct for the correct, honourable and proper fulfillment of public functions. These standards are intended to prevent conflicts of interest and ensure the proper conservation and use of resources entrusted to government officials in the performance of their functions and include the following:

(a) Measures and systems requiring government officials to report to the appropriate authorities acts of corruption in the performance of their public functions.

(b) Mechanisms to enforce these standards such as instructions to government officials to ensure their proper understanding of their responsibilities and the ethical rules governing their activities.

(c) Declaration of income, assets and liabilities of persons who perform public functions in certain posts and, where appropriate, for such declarations to be made public.

(d) Systems for government hiring as well as for the procurement of goods and services to ensure openness, equity, and efficiency of such systems.

(e) Adequate procedures for government revenue collection and control systems to deter corruption and promulgation of laws that deny favourable tax treatment for individuals and corporations for expenditures made in violation of anti-corruption laws.

(f) Systems for protecting public servants and private citizens who, in good faith, report acts of corruption.

(g) Oversight bodies to implement modern mechanisms for preventing, detecting, punishing, and eradicating corrupt acts.

(h) Measures to deter bribery of domestic and foreign officials.

(i) Participation of civil society and non-governmental organization in efforts to prevent corruption.

(j) Conducting studies of further preventive measures that take into account the relationship between equitable compensation and probity in public service.

IACAC emphasized that corruption undermines the legitimacy of public institutions and strikes at society, moral order and justice, as well as at the comprehensive development of peoples; and fighting corruption strengthens democratic institutions and prevents distortions in the economy, improprieties in public administration and damage to a society’s moral fiber. It further stated that preventing and fighting corruption involves taking appropriate action against persons who commit acts of corruption in the performance of public functions or acts specifically related to such performance; and there is a need to strengthen participation by civil society in the fight against corruption.

In October 2023, Guyana underwent its sixth round of on-site review through the Follow-Up Mechanism for the Implementation of the Inter-American Convention against Corruption (MESICIC) which is the anti-corruption mechanism of the Organisation of American States (OAS). The MESICIC experts review domestic laws and institutions to determine if they are in conformity with the provisions of the Convention and to assess their effectiveness in preventing and combating corruption. As part of this review process, the experts visit the country being reviewed and meet with government officials and civil society organizations to gather more information. At the end of the review, a report is compiled containing recommendations to strengthen its anti-corruption architecture to prevent and combat corruption. Additionally, the Authorities are required to report periodically to the OAS on progress made on the recommendations made.

Integrity Commission Act 1997

The Integrity Commission Act was passed in July 1997 and assented to by former President Samual Hinds in September 1997, nearly two years after the tabling of the draft Bill. The idea of having such a body in place therefore preceded Guyana being a signatory to the IACAC. The main purpose of the Act to provide for the establishment of an Integrity Commission and to make provisions to secure the integrity of persons in public life. A person in public life is one who holds a specified office as outlined in Section 42 as well as Schedule I. It, however, took two years for the Act to become operationalised with the appointment of three members of the Commission exclusively from the religious community.

A dispute subsequently arose in the re-appointment of the chairperson and other members of the Commission without consultation with the Leader of the Opposition. This resulted in the filing of a judicial review on the matter. As a result of the court action, the late Bishop George resigned from the position of chairperson in 2006. Without a quorum, the Commission could not have proceeded with its work. From then on until 2018, the Commission functioned without the services of a chairperson while the two other members ceased to function with effect from May 2012.

Additionally, annual budgetary allocations over the years were woefully inadequate to enable the Commission to discharge its mandate effectively. This had resulted in the last Commission, appointed in 2018, to restrict its work to the mere monitoring of the submission of the annual financial returns of income, and assets and liabilities of those public officials who are required to file their returns with the Commission. This practice continues to date although there have been increased budgetary allocations. These matters have caused us to question the seriousness of successive Administrations in ensuring that a fully functioning Commission is in place as the leading agency in the fight against corruption in government. It should not be over-emphasised that any reform initiative that is not a voluntary act but is insisted upon by external funding agencies as conditionalities for the grant of loans and other forms of assistance, is likely to result in minimal compliance, and in some cases non-compliance.

The Act requires every person in public life to make an annual financial declaration of income, assets, and liabilities to the Commission, including those of the spouse and children. The Commission examines these declarations and make such enquiries as it considers necessary to verify their completeness and accuracy. It may request the declarant to furnish additional information relating to his/her financial affairs. The failure to file a declaration or to submit additional information will result in the publication of the fact in the Official Gazette and in a daily newspaper.

By Section 22, any person shall be liable, on summary conviction, to a fine of $25,000 and imprisonment for a period of between six months and one year, if he/she:

(a) Fails, without reasonable cause, to file with the Commission a declaration which he is required to file.

(b) Knowingly files with the Commission a declaration that is not complete or is false in a material way.

(c) Fails, without reasonable cause, to comply with a request for additional information or gives incomplete or false information pursuant to the request.

(d) Fails, without reasonable cause, to attend an inquiry being conducted in relation to his/her declaration.

While the Act vests with the Commission the powers of prosecution, the approval of the Director of Public Prosecution must first be sought. Where the offence involves the non-disclosure by the declarant of property which should have been disclosed in the declaration, the magistrate convicting the person shall order the person to make full disclosure of the property within a given time. Failure to comply with the order within the given time, the said offence shall be deemed to be a continuing offence and the person shall be liable to a further fine of ten thousand dollars for each day on which the offence continues.

Schedule II of the Act also provides for a Code of Conduct to be observed by persons in public life. Any person is in breach of any of the provisions of the Code shall be liable, on summary conviction, to a fine of $25,000 and to imprisonment for a period of not less than six months nor more than one year. The Code was revised and published in the Gazette on 13 June 2017. Any person who believes that there has been a breach of the Code can file a complaint with the Commission which is obliged to investigate the complaint. If the Commission determines that there is merit in the complaint, it shall hold a public hearing of the matter. At the conclusion of the hearing, the Commission is required to submit a report to the DPP if it considers it necessary. Where the DPP is satisfied that a breach of the Code has occurred, it shall initiate criminal proceedings against the person in public life.

Considering the above, the Integrity Commission has a lot more to do, if its work is to be viewed as effective and an important mechanism in the fight against corruption and mismanagement of State resources.

– To be continued