Oby Ezekwesili, Co-founder of TI

This week’s Transparency International (TI) weekly newsletter reported that a businessman with ties to Spain’s ruling party was sentenced to 51 years in prison for bribing senior ruling party officials in exchange for the award of procurement contracts. Earlier in the week, the Prime Minister was ousted from office based on a motion of no confidence approved by the country’s parliament.

Since 2012, Spain has lost 12 points on the Corruption Perceptions Index.

TI has also announced that nominations for the Anti-Corruption Award 2018 are now open. The award is made for the courage and determination of the many individuals and organisations fighting corruption around the world. The winners will be announced in October in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Introduction

The Estimates for Revenue and Expenditure for the fiscal year 2018 were presented in the National Assembly on 27 November 2017 and were approved before the end of the year. This is the second consecutive year that this was done. According to the Minister of Finance, “[b]y presenting Budget 2018 before the beginning of the fiscal year, Budget Agencies continued to have an improved opportunity to plan and implement their annual budgets, thereby allowing programmes that are critical to our country’s development to move forward with greater efficiency”.

The Ministry of Finance has issued an End of Year Report for 2017 on 12 April 2018, the second of its kind. The report clarified that the economic and fiscal data presented in the 2018 Estimates were based on the actual data available at the time of the compilation of the Estimates as well as forecasts for the remainder of the year. It therefore provides an updated position as of February 2018 in relation to the data presented in the Estimates.

The issuing of the End of Year Report should not be confused with the provision of Section 68 of the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act which requires the Government to prepare an End of Year Budget Outcome and Reconciliation Report. This is a component of the annual consolidated financial statements to be audited and reported on by the Auditor General. The current deadline for the submission is 30 September following the close of the fiscal year. It therefore continues to be a welcome development that, although not a legal requirement, an End of Year Report is being prepared. According to the report, this is done “[t]o support full transparency and accountability regarding both fiscal performance and the accuracy of economic forecasting”.

In this article, we highlight the key aspects of the report as it relates to the macroeconomic variables.

GDP Growth

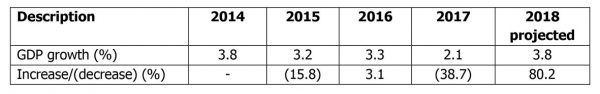

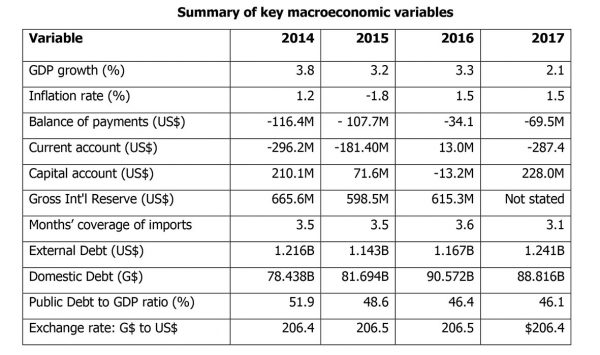

The adjusted growth in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for 2017 was 2.1 percent, compared with 3.8 percent as reflected in the 2017 Estimates. The latter was adjusted downwards to 3.1 per cent in the 2017 Mid-year Report and to 2.9 percent at the time of the preparation of the Estimates for 2018. The report attributed this significant decline in GDP to lower than expected outputs in mining and quarrying, construction sector, sugar and livestock, and was significant enough to offset increased performance in other areas of agriculture, fishing, forestry, mining and services sectors.

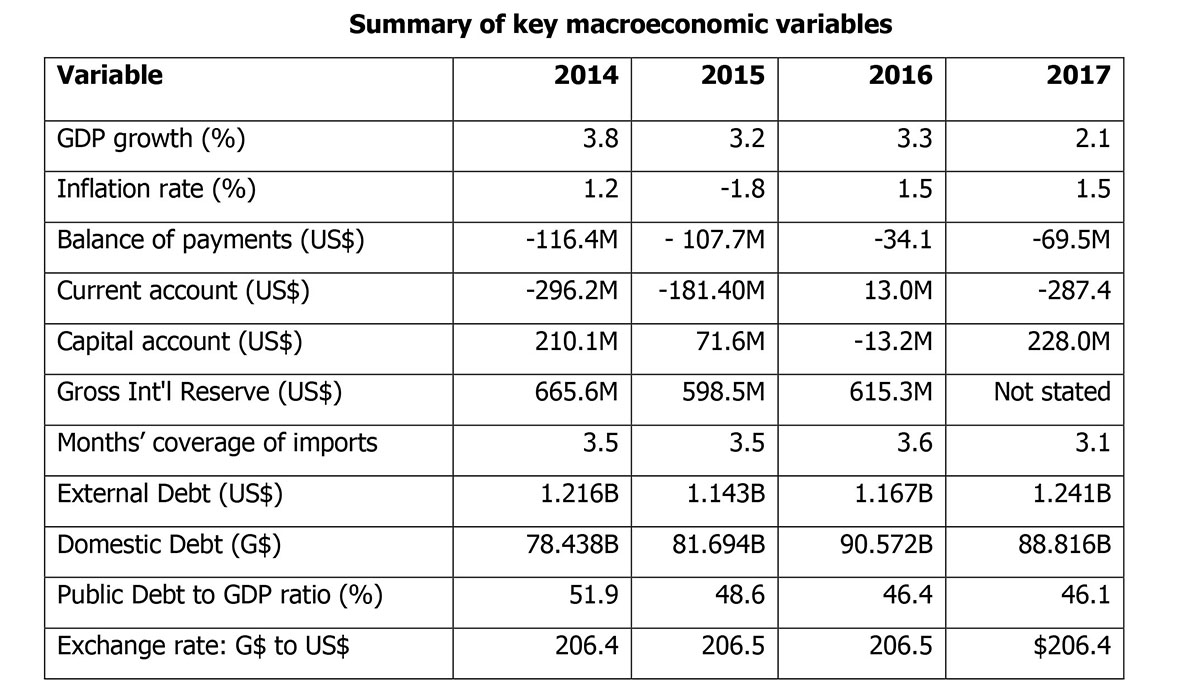

Shown below were the actual GDP growth rates over the last four years as well as the projection for 2018:

The 15.8 percent decline in GDP growth in 2015 might have been influenced by the following: (i) 2015 was an election year; (ii) elections were held close to mid-year where the private sector organisations would have been more cautious in the run-up to the elections; and (iii) there were severe restrictions in Government spending for a greater part of the year since no budget was in place until August 2015. Government spending, to a large extent, influences economic activities in the private sector.

The decrease of 38.7 percent in the GDP growth in 2017 is, however, a cause for serious reflection by policy makers. Were there enough fiscal incentives to enable the productive and service sectors to perform so as to achieve the desired growth rate? Or were there other factors, such as adverse weather conditions, which affected the productive capacity of the economy? The 2018 Estimates indicate a forecast GDP growth of 3.8 percent. Is this forecast not an over-estimation, having regard to our economic performance in 2017, global economic trends and internal factors, to which the Minister referred in his Budget Speech? Are we likely to see a downward revision in the 2018 Mid-Year Report? Last Saturday, the State newspaper, the Guyana Chronicle, reported on the Minister of Finance’s address to the 48th Annual Meeting of the Board of Governors of the Caribbean Development Bank. In that report, it was stated that the projected GDP growth rate for 2018 has been lowered to 3.4 percent, though no mention of this was made in the End of Year Report for 2017.

In our column of 11 December 2017, we referred to the Minister’s presentation of the 2018 Estimates in which he indicated that the Government was able to maintain stable macroeconomic fundamentals, despite constraints due to the lack of economic diversification that left key sectors and industries vulnerable to external shocks and internal meltdowns. The Minister had identified weak performances in the mining and quarrying sectors, and the sugar and forestry industries as having contributed to the less-than-expected economic growth.

In that column, we had stated that the 2018 budget measures did not attempt to address how the economy could be diversified nor how it could be insulated against the shocks and meltdowns referred to by the Minister. Except for forestry and gold mining (where the proposed measures are modest), concrete measures were to a large extent absent relative to the other areas of the economy, and there was no reference of possible any new areas in an effort aimed at diversification. In particular, there was hardly any mention of GuySuCo which is major contributor to foreign exchange and the GDP growth, notwithstanding its loss-making status and consequent drain on the Treasury. GuySuCo is currently faced with serious governance problems in the wake of its on-going restructuring, which will almost inevitably result in a further lowering of its productive capacity and possible loss in the much-needed foreign exchange.

Balance of Payments

The Current Account recorded a deficit of US$287.4 million in 2017, compared with a deficit of US$12.4 million in 2016, an increase of US$275.0 million. This indicates that export earnings were significantly less than the value of imported goods and services. Unless appropriate action is taken to boost export earnings, the country’s reserves are likely to be adversely affected; there is going pressure on the Guyana dollar to maintain its value; and the GDP growth will remain sluggish.

The Capital Account improved from a deficit of US$13.2 million in 2016 to a surplus of US$228.0 million in 2017, due mainly to larger-than-expected inflows from foreign direct investments. The overall result was that the Balance of Payments Account reflected an increased deficit of US$14.3 million from US$53.3 million at the end of 2016 to US$69.5 million in 2017. The deficit was financed by US$1.9 million in debt relief, US$55.6 million in debt forgiveness, and drawdowns of US$12.1 million in net foreign assets at the Bank of Guyana.

Inflation Rate

The inflation rate was 1.5 percent which was 0.5 percent lower than was projected in the 2018 Budget.

Interest Rate

Interest rate on small savings was 1.1 percent while the commercial banks weighted average lending rate was 10.19 percent. The 182 days Treasury Bills attracted an interest rate of 1.1 percent; 364 days Bills, 1.2 percent; and 91 days Bills, 1.54 percent.

Exchange Rate

The exchange rate remained stable during the year at US$1 = $206.5.

Reserves cover

The gross reserved of the Bank of Guyana amounted to approximately 3.1 months of import cover at the end of 2017.

Central Government Revenues and Expenditure

A fiscal deficit (after grants) of $33.4 billion was recorded in 2017, equivalent to 4.5 percent of GDP, mainly due to lower- than-projected current expenditure coupled with higher-than-projected revenues. Total Central Government expenditure was $240.3 billion, of which employment costs accounted for $54.5 billion or 22.7 percent. On the other hand, capital expenditure recorded a one percent increase over the projected expenditure of $58 billion, due mainly to better performance of the Public Sector Investment Programme in relation to local funding.

Public Debt

The total public debt at the end of 2017 was US$1,670.7 million which was US$8.4 million higher than projected. The external debt was US$1,240.6 million, representing 73.4 percent of the total debt stock. The debt to GDP ratio was 46.1 percent, compared with 45.2 percent projected.

Summary of economic performance: 2014-2017

The following table presents a summary of the key macroeconomic variables over the last four years:

Conclusion

It is evident that the macroeconomic fundamentals reflect a stable economy. However, the lack of a diversified economy as well as external shocks are stymieing efforts to achieve the desired level of growth. While we may feel elated in the belief that the problem will be solved when oil revenues begin to flow in 2020, the overdependence on oil creates its own problems, as several oil-producing countries have experienced. Besides, oil reserves are a depletable resource, and in our case, they will be completely exhausted in 15 years, based on the estimated rate of extraction.

While the proposed Sovereign Wealth Fund, if carefully managed, is likely to provide some cushion, there is no substitute for a diversified economy. It is our hope the advice of the International Monetary Fund would be heeded to as to how much of the oil revenues should be set aside for the “rainy day”, bearing in mind that the natural resources of a country belong to its citizens; and oil revenues represent the conversion of a natural asset into a financial asset. The latter should be preserved for posterity; otherwise, we will end up eroding our capital base.

A particular area of concern relates to the fiscal deficit. Over the last 25 years and possibly longer, public expenditures have outstripped revenue collections, indicating clearly that we have been living beyond our means. In order to finance the deficit, we continue to borrow. One shudders to think what would have been the consequences, had there not been debt scheduling, debt write-offs, balance of payments support and other forms of financial assistance from international lending agencies and bilateral donors.