Introduction

It would have been, after all, the largest single loan ever taken by this country, and on a per capita basis, the largest loan ever extended to a member country by the Islamic Development Bank. The Ministry of Finance later walked back on that statement, clarifying that it was rather a “resource envelope of US900M that is potentially available from which the Government of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana can borrow.” The ministry’s clarification said that during the period 27-29 November 2017, the IsDB mounted a mission to Guyana to develop a medium term work plan for the period 2018- 2022, setting out a pipeline of projects that the Bank can support over the next five years.

As Guyana moves to First Oil – and let us face it, into general and regional elections – the temptation to spend will be almost irresistible, posing a risk to the much anticipated Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF). That risk is real and cannot be discounted. So far, the discussion on the SWF has largely been theoretical and centred on possible models. In practice, the SWF has to take a whole host of factors into account, including the country’s recurring deficits which are financed by loans; the deficit in its infrastructure; future revenue gains and losses; commodity prices including that of oil; and citizens’ expectations which continue to rise.

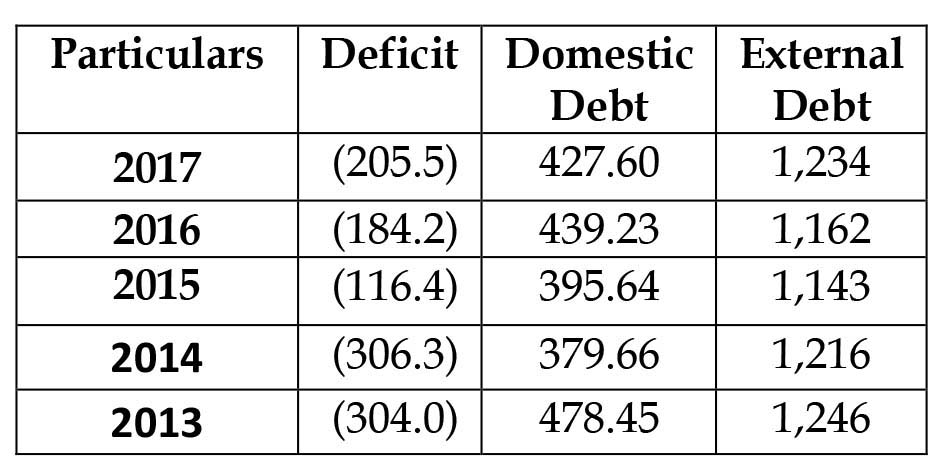

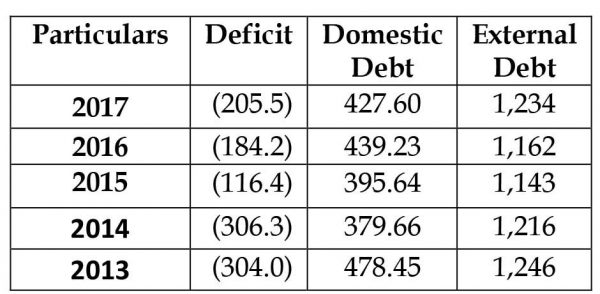

Losses and debts

For as long as I can remember, the national Budget has been running substantial losses and these have translated into increased domestic and external debts. A ballooning in spending not financed by increased revenue will only exacerbate the situation with the effect that there will be no resources to be put into the SWF, in the early years of oil production.

Let us look at the deficit for the past five years as well as the domestic and external debts, showing the most recent year first.

Looking at the deficit first, it is uncertain whether revenues from oil for part year 2020 and full-year 2021 will cover the deficits for those years. The variables are simply too many, and too substantial to offer an acceptable level of comfort in making projections. For example, will the Government pursue restraint in spending or does it see its electoral prospects tied to uncontrolled borrowings? It has to contend too, with the vagaries of the oil market and the production cost of oil which determine the country’s share of oil revenues.

Second, the implications on these numbers of any borrowing of the magnitude contemplated by Minister Jordan will rupture the existing permitted ceiling under the External Loans Act which authorises the raising of foreign loans for the broad purpose of financing the general development of Guyana. That Act places a ceiling on borrowing at four hundred billion dollars in the aggregate, or roughly US$1.9 billion.

The Act does however, give the Minister the power to increase the limit by way of an order which is subject to affirmative resolution. That means that any increase in the borrowing ceiling has to be approved by the National Assembly before it becomes effective. The Act also requires that a copy of every agreement for a loan under the Act must be laid before the National Assembly as soon as practicable, and that the repayment of the sums borrowed and all interest and other charges payable thereon are charged on the Consolidated Fund.

Greenidge’s US$15 million legal fund

Mr. Winston Jordan was not the only Minister whose utterances have caused some concern. He was joined shortly after by former Finance Minister and now Foreign Minister Carl Greenidge who in a report on Guyana’s case to the International Court of Justice thoughtlessly and astonishingly signaled to the world – and to the lawyers retained by the Government to pursue its case – that US$15 million dollars might not be enough to pay them! Such a sum is quite substantial even applying the hourly rates of the high priced lawyers in New York and London which varies between US$750 and US$1,000 per hour.

A legal team is made up of a number of persons of varying levels of experience and commanding different hourly rates so that the average is less than the top rate. But even if one uses the top hourly rate of $1,000 as the average, the number of hours would be 15,000 hours or the equivalent of one thousand, eight hundred and seventy-five lawyer days, or three hundred and seventy-five weeks or more than seven years. Even if there are seven lawyers in Greenidge’s legal team, they would be working fifty-two weeks at US$8,000 per day! And all this while the other party has publicly stated that it will not appear in the matter.

Guyanese senior counsel not good enough

So far, Minister Greenidge has not disclosed the names of the lawyers to allow us to determine whether any Guyanese lawyers have been included, of whom Dr. Barton Scotland and Professor Duke Pollard come immediately to mind. With the greatest of respect to Sir Shridath Ramphal who seems to be leading the process, he is a great diplomat but not an international lawyer. I have spoken to some legal minds and they have expressed more than mild surprise at the strategy underlying the case brought by Guyana. To raise the question of Ankoko at this stage is dangerous since it raises the issue of territory. Or to ask the ICJ to have Venezuela refrain from threatening or using force which is clearly prohibited under the UN Charter. A US$100 per hour lawyer is likely to know that.

The facts in this Venezuela and now Guyana controversy case are not in dispute and the case really turns on the question whether a posthumous declaration by a junior lawyer in an Arbitral hearing some sixty years earlier can upend an international settlement unanimously agreed, respected and upheld for more than sixty years.

The irony of this all, is the strongly held view that Venezuela’s so-called claim was engineered by the duplicitous Americans to undermine Cheddi Jagan when it was feared that he might lead British Guiana into independence. Fifty years later, a Guyana branch of a Bahamas subsidiary of the American powerhouse ExxonMobil gives Guyana US$18 million of which US$15 million is to be used as a legal fund for which it is a primary beneficiary.