We also stated that the changes being made in the new agreement may provide important lessons for the Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME) of which Guyana is a member. In today’s article, we conclude our discussion on the subject.

NAFTA’s achievements

Any analysis of NAFTA’s achievements would be affected by certain significant but unrelated events that took place over the last 25 years, the most notable being the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York; and the World Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 and the recession which followed. Another consideration is the extent to which developments that took place among the parties to the Agreement subsequent to 1993, could have happened had there not been a NAFTA. What can be said with some degree of certainty is that NAFTA became ‘the template for hundreds of subsequent free trade agreements’. Mexico has eleven Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with 46 countries, while the United States has 14 FTAs with 20 countries. Canada’s FTAs with more than 40 countries are at various stages of implementation.

Some researchers have argued that the overall economic impact of NAFTA is difficult to measure since trade and investment trends are influenced by various variables, such as economic growth, inflation, and currency fluctuations. They suggest that ‘[m]ost of the trade-related effects of NAFTA may be attributed to changes in trade and investment patterns with Mexico because economic integration between Canada and the United States had already been taking place’. Others believe that as a result of NAFTA, there was ‘unprecedented integration between Canada’s and the United States’ developed economies and Mexico’s developing one… It encouraged regional trade to more than triple, and cross-border investment between the three countries also grew significantly’.

Trading activities

In 1993, trade among the NAFTA partners was $290 billion. By 2016, this figure rose to $1.1 trillion. Canada and Mexico were the leading markets for U.S. exports, accounting for more than one-third of total U.S. exports. Together, they also accounted for more than one-quarter of U.S. imports. During the same period, U.S. direct foreign investment in Mexico grew from $15 billion to more than $100 billion, a six-fold increase. Similarly, Mexico’s exports increased six-fold from $60 billion in 1994 to $400 billion in 2013, and there was a corresponding increase in imports, resulting in better quality of goods and services at lower prices.

This significant increase in trading activities, however, has had a corresponding downside effect on the U.S. trade deficit with its other NAFTA partners, since the United States imports more from Mexico and Canada than it exports to these countries. In 1993, the U.S. trade deficit in goods with these two countries was $9.1 billion. By 2017, it increased almost ten-fold to $89.6 billion. In respect of services, the United States nevertheless recorded a trade surplus of $31.4 billion in 2016.

Economic growth

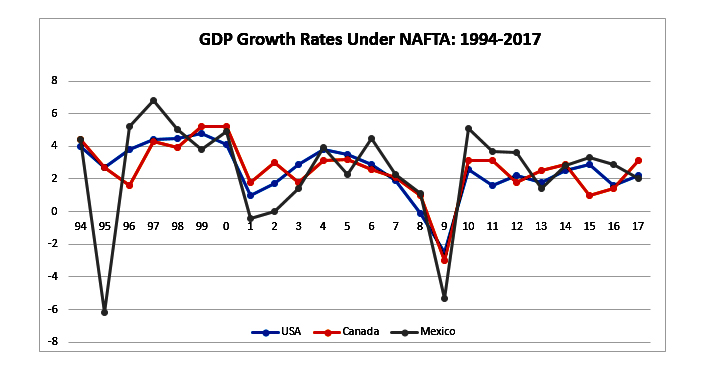

Mexico’s annual GDP growth rate over the period 1994-2017 averaged 2.4 percent. This was lower than those of other Latin American countries, such as Brazil, Chile and Peru. For the same period, the United States and Canada recorded average growth rates of 2.5 percent and 2.6 percent respectively. The graph below shows the annual growth rates of the three countries for the period 1994-2017:

Mexico’s negative GDP growth of 6.2 percent in 1995 was due mainly to the ‘Tequila Crisis’ resulting from the devaluation of the Mexican currency in December 1994 which many economists believed was overvalued. This action triggered capital flight and the ensuing economic recession. However, the economy quickly recovered in 1996. Two other events adversely affected the economic performance of the three countries: the 2001 attack on the World Trade Centre in New York; and the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis. Ignoring the years 1995, 2001, 2008 and 2009, the average GDP growth rates over the NAFTA period were as follows: United States: 3.0 percent; Canada: 3.0 percent; and Mexico: 3.5 percent. This performance compares favourably with that of the EU which recorded an average annual growth rate of 1.79 percent during the period 1996-2018.

Immigration

Former U.S. Secretary of State George Schulz argued that in 2014 there was no immigration problem from Mexico anymore and that the net immigration of Mexicans to the United States was negligible. He suggested that more U.S. citizens went to Mexico than the other way around. And according to the Economist of 16-22 March 2019, migration from Mexico was reduced by 90 percent from its peak in 2000, and most of the migrants are from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

At the end of March 2019, the U.S. Administration suspended aid worth $700 million to these three countries and has threatened to close the U.S.-Mexican border. If this threat is made good, legitimate border crossings and daily trade worth $1.7 billion will be disrupted, and some five million U.S. jobs will be affected.

Referring to the one million Canadians living in California, Schultz suggested that:

If we can create a situation where people move to where they are productive and fruitful and have jobs and find a good life, why not? The facts underlying the demographic situation gives that opportunity a chance… In our immigration debate, we’re worrying about the wrong border… The problem is the southern border of North America, the Mexican southern border…

Employment

Various figures have been quoted as to the extent of job losses in the United States during the NAFTA period. Some critics argue that NAFTA was responsible for the loss of up to 600,000 manufacturing jobs over two decades. The automobile sector lost some 350,000 jobs since 1994, while in Mexico employment in this sector increased from 120,000 to 550,000. However, the U.S. economy added just over 25 million jobs during the NAFTA period, of which nearly 20 million took place under President Clinton. According to one analyst, ‘nearly all economic studies say NAFTA’s net effect on jobs was negligible’.

Some economists attribute the loss of U.S. jobs to the surge in U.S. imports while at the same time acknowledging that some of it would have likely to happen even without NAFTA. Others were quick to point out that jobs began to decline before NAFTA. Yet other economists argue that ‘increased trade produces gains for the overall U.S. economy. Some jobs are lost due to imports, but others are created, and consumers benefit significantly from the falling prices and often improved quality of goods created by import competition’.

Critics consider that NAFTA was responsible for the plight of some two million Mexican farmers since they could not compete with their U.S. counterparts whose operations are subsidized. This has resulted in illegal migration to the United States. After 1994, both legal and illegal migration more than doubled, peaking in 2007. However, the flow began to reverse in 2008 due mainly to stricter border controls and more job opportunities in Mexico.

Wage gap

Because of immigration restrictions, the wage gap between Mexico and the United States has not narrowed. In 1997, average wages in the manufacturing sector in Mexico were about 15 percent of U.S. wages. By 2012, this figure had risen by a mere three percent. Poverty levels in Mexico remain at the same level as those of 1994.

Foreign direct investments

During the period 1993 to 2015, there was a significant growth in foreign direct investments (FDIs) among the NAFTA countries. FDIs from the United States into Mexico increased from $15.2 billion to $92.8 billion, nearly half of which relates to the manufacturing sector. Similarly, Mexico’s FDIs into United States increased from $1.2 billion to $16.6 billion. Canada has seen a significant increase in FDIs from the United States, moving from $69.9 billion in 1993 to $352.9 billion in 2015 and representing 49.4 percent of all FDIs into Canada. Canada’s FDIs into the United States also increased from $40.4 billion to $269.0 billion, a more than six-fold increase.

Small and medium-sized enterprises

Prior to NAFTA, large companies dominated trade with Mexico because they could build factories and offices there. SMEs were unable to do so because of cost implications. The removal of the residency requirements as well as the elimination of tariff and non-tariff barriers present new opportunities for these businesses. NAFTA has created a level playing field for all types of businesses regardless of size. However, these businesses are still required to adhere to the relevant Mexico’s laws and regulations (including taxation laws), and hiring practices, among others.

Environmental matters

Environmental groups had contended that the measures contained in NAFTA were inadequate to protect and conserve the environment. In particular, Mexico’s regulatory and legislative frameworks were inadequate. As a result, the NAAEC was entered as a side agreement to NAFTA. Suffice it to state that there were no environmental disasters caused by industrialization in Mexico.

Conclusion

By most accounts, NAFTA has had a positive effect on the economies of the United States, Canada and Mexico which are now well integrated. By eliminating trade barriers as well as tariffs/duties, NAFTA has created a single market by developing cross-border supply chains and just-in-time inventory systems, including the availability of intermediate goods. This has resulted in lower costs, increased efficiency and productivity, and enhanced competitiveness.

While there is some merit in revisiting NAFTA in the light of developments since 1994 especially in relation to information technology, it is certainly not the ‘worst trade deal’ entered into by the United States. Mexico has been the main beneficiary, moving from a virtually closed economy with high regulatory and protectionist environment to an open one that is more export-oriented. NAFTA also facilitated the modernization of Mexico’s industries.

Most of the provisions of NAFTA have been incorporated into USMCA in reorganized and expanded form. USMCA is in effect a revised or updated version of NAFTA, and not a disbandment and replacement of it because of any significant deficiencies. Considering the benefits and impact achieved over the years under NAFTA, would suggest that most of its criticisms are unjustified.

The late U.S. President George H.W. Bush had the following to say of NAFTA:

NAFTA has stood the test of time…we knew getting this deal done wouldn’t be easy…But we stayed the course, because in the end we believed that economic reform would contribute to increased political stability and democracy in the Western Hemisphere. We believed that not only would trade benefit our neighbors, it would open new markets – new opportunities – for tens of millions of businesses and investors.

(For feedback/comments on this article, please contact author at swatantra.goolsarran@gmail.com)