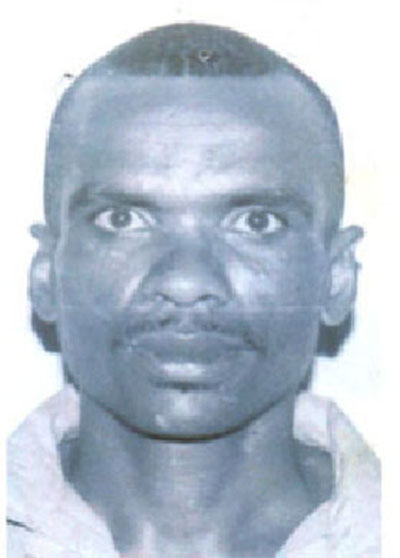

Sentenced to 66 years in prison in 2014 for the murder of his neighbour, Abiola Eadie, whom he killed during a row over an injured game cock, Mark Assing has appealed his conviction for the capital offence.

The matter came up for hearing yesterday morning before acting Chancellor Yonette Cummings-Edwards and Justices of Appeal Rishi Persaud and Dawn Gregory at the Guyana Court of Appeal.

In his notice of appeal, he argues, among other things, that the judge who conducted his trial wrongly admitted hearsay evidence from a witness for the state that was more prejudicial than probative in his case, thus resulting in a substantial miscarriage of justice.

He says that the judge also failed to adequately direct the jury on how it needed to approach issues of conflict, inconsistencies and omissions in evidence, again resulting in a miscarriage of justice.

Through his attorney Glenn Hanoman, Assing (the appellant) also contends that the judge withdrew the possibility of a conviction for the offence of manslaughter “by materially misleading the jury” on the issue of provocation.

During arguments yesterday, Hanoman said that having alerted the jury to the possibility of a verdict for both murder and manslaughter, the judge failed to employ a procedure that permitted a conviction for manslaughter.

According to him, the judge failed to adequately assess all the evidence and statements that tended to establish the factual circumstances that could lead to provocation and completely ignored the unsworn statement during this exercise.

At yesterday’s hearing Hanoman said that the trial judge made a grave error in telling the jury that it needed to first find the accused guilty of murder before going on to consider a verdict for manslaughter.

From the notice of appeal seen by this newspaper, the appellant is of the view that the judge misdirected the jury regarding the formula to be used in arriving at a manslaughter verdict.

Assing said, too, that the judge failed to put his defence fairly, adequately and with balance to the jury, which prejudiced his case.

The appellant has expressed the view that the judge misdirected the jury on the reliability of the pathologist’s evidence by introducing a presumption that his evidence enjoyed a status above that of other witnesses.

Hanoman recalled that the judge had told the jury, “I would hope,” that if you were to reject the doctor’s autopsy findings, that you have good reasons for so doing.

Counsel advanced that this expression of a personal position by the judge – “I would hope” – could have operated against his client and result in a much skewed view of how the jury may have viewed his testimony.

Hanoman explained that so potent could that direction from the judge have been, that it could have influenced the jury, who are the sole arbiters of the facts, into not rigorously interrogating the pathologist’s findings.

The lawyer made this observation, while noting that though the doctor had said that death would likely result immediately following the type of injuries Eadie sustained, she died some two weeks later.

Prosecutor Diana Kaulesar-O’Brien, however, argued that there was no break in the chain of causation from the injuries Assing inflicted on the woman, to the time of her death, and therefore he was still held liable.

She said that those wounds were still the substantial operating cause of death at the time Eadie died.

Finally, the appellant complained of his sentence being too severe.

On this point he said that the trial judge utilised a mathematical formula which has no legal basis in imposing the sentence of 66 years, while adding that he failed to take into account established sentencing guidelines.

Assing further contends that in passing sentence, the judge failed to explore the possibility of ordering a probation report and to take other relevant factors into consideration. The appellant is of the view that the sentence was too severe in all the circumstances of the case.

Following the hearing, Chancellor Cummings-Edwards informed that the court will reserve its decision and will dispatch notices informing when the judgment will be delivered.

During his trial in 2014, Assing had claimed that it was Eadie’s brother, whose name was given as ‘Buck Man,’ who had shot her by accident. Assing said that ‘Buck Man’ had struck him with a gun, which caused it to go off, hitting Eadie.

He had also said that he was physically incapable of pulling a trigger, as he was born without the ability to bend the index finger of his right hand, which was his dominant hand.

In passing sentence, Justice Navindra Singh, who presided over the trial, noted that there was overwhelming evidence against Assing and that though he knew he was guilty he had wasted the court’s time by not confessing.

Justice Singh had further said that Assing chose to deem the testimonies of the prosecution’s witnesses as untrue and blame the murder on someone else.

Justice Singh began with a sentence of 60 years, before adding 8 years because a gun was used to commit the murder and subtracting the 2 years Assing spent on remand while awaiting trial.