Alone I stand in the autumn cold

On the tip of Orange Island,

The Xiang flowing northward;

I see a thousand hills crimsoned through

By their serried woods deep-dyed,

And a hundred barges vying

Over crystal blue waters.

Eagles cleave the air,

Fish glide under the shallow water;

Under freezing skies a million creatures contend in freedom.

Brooding over this immensity,

I ask, on this bondless land

Who rules over man’s destiny?

I was here with a throng of companions,

Vivid yet those crowded months and years.

Young we were, schoolmates,

At life’s full flowering;

Filled with student enthusiasm

Boldly we cast all restraints aside.

Pointing to our mountains and rivers,

Setting people afire with our words,

We counted the mighty no more than muck.

Remember still

How, venturing midstream, we struck the waters

And the waves stayed the speeding boats?

Mao Tse Tung (1925)

On Lady Yang

Sing not of Lady Yang’s regret of days gone by!

The Silver River severs on earth as on high.

In Stone Moat Village when the man parted from his wife,

More tears were shed than in the Palace of Long Life.

Yuan Mei (1716-1798)

On Verse Writing

It’s hard to make a verse which could afford delight;

I cannot feel at ease till I write and rewrite.

An old beauty should make up like a maiden fair;

She would not show herself unless she’s dressed her hair.

Yuan Mei (1716-1798)

On Poetry

Li Bai’s and Du Fu’s verse are read from mouth to mouth,

But now they cannot arouse our emotion new.

Talents emerge from age to age, from north to south;

To lead in verse for hundred years each has his due.

Zhao Yi (1727-1814)

Yesterday, the Lantern Festival was celebrated in China and in the Diaspora. It marked the last day in the festive period of the Chinese Lunar New Year 2020, and the Spring Festival that is observed at this time. This Spring Festival has been observed since the New Year’s Eve on Saturday, January 25, the last day of the previous year, ushering in New Year’s Day, January 26, the Year of the Rat.

The Lantern Festival is held on the fifteenth day of each new year. It is marked by elaborate decorations consisting mainly of brightly coloured lanterns dominated by red, as well as customs and traditions. This festive season, with the new year celebrations, the Spring Festival and the Lantern Festival, and the way they are observed, has its origin in myths, legends and traditions from ancient China.

Among the customs in the Lantern Festival is the lighting of sky lanterns, also known as Chinese lanterns and Kongming lanterns. These colourful lanterns can be released towards the sky. The festival originated more than 2,000 years ago and among the tales of its origin is the story of the Kongming lanterns and tribute paid to their inventor. Zhu Geliang (181 – 234 AD) was known as the greatest military strategist in Chinese history. He was called Kongming and the lanterns he invented were named after him.

One story is that he first released the lanterns to send messages in times of war and was once rescued when he was surrounded by the enemy because these messages were read by his allies when the lanterns floated to them. Another story is that the people’s homeland was besieged by invaders and they fled to the mountains. When it was safe for them to return the lanterns were set off to inform them. They returned home and to celebrate that day, they would always light up the lanterns.

There is also the version (according to Encyclopaedia Britannica) which says 2,000 years ago, Emperor Ming of the Han Dynasty observed that Buddhist monks would hang lanterns in the temples on the fifteenth day of the year. He decided to instruct all households to hang lanterns on that day and the practice survived and grew into the festival that it is today. Other customs include the cooking and eating of Chinese rice dumplings, performances of the Lion Dance, and the solving of riddles which are written in the lanterns.

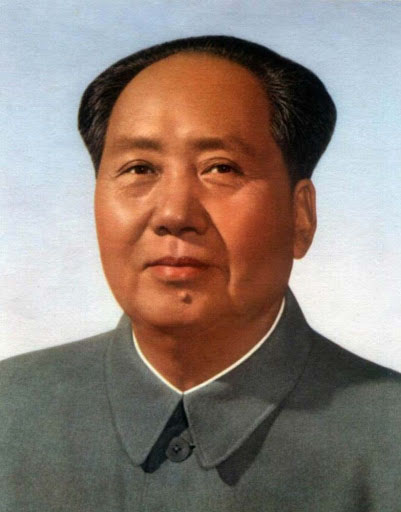

In honour of these Chinese New Year observances, the Confucius Institute at the University of Guyana sourced samples of Chinese classical poetry translated by the highly acclaimed scholar and translator Xu Yuanchong, and one modern poem. The classical samples are taken from the Qing Dynasty (1616 – 1911), while the modern selection is from the poetry of Mao Tse Tung, first Chairman of the Communist Party of China and leader of the People’s Republic of China from 1949 to 1976.

The classical pieces tell of poetry – the writing of verse, and of legends. The first selection refers to Lady Yang (719 – 756), described as one of the most beautiful women of ancient China. She was the favourite mistress of the Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty (source Xu Yuanchong). She is cited in other poems since she became a legendary figure of love because her affair with the emperor ended in tragedy.

The other selections reflect on the writing of poetry and its difficult tasks. This is an age-old topic in poems from the western culture as well. Significant here is the reference to Li Bai (701 – 762) and Du Fu (712 – 770). Li Bai was the greatest romantic poet of the Tang Dynasty, while Du Fu was the greatest realist poet in the same period (according to Xu Yuanchong). It is interesting to see the styles of the poetry in those genres and to compare them to the modern selection.

The comparison is of particular interest considering the poems of Mao Tse Tung or Mao Zedong (1993 – 1976) popularly known as Chairman Mao. He is universally acknowledged as a political leader and great statesman, hardly known as a poet. Although he was writing since the 1920s, his poems were first published in February 1957 in a new magazine in China – Shih-K’an. (source, Cambridge University Press, February 2009). It should not be surprising that Mao should write poetry, since throughout the history of China, several political leaders and statesmen have also been poets. Mao, therefore, continued that tradition in modern times.

Surprising, however, is that despite his radicalism, his art is conventional – he writes in the style of classical Chinese poetry (Cambridge University Press, February 2009). This poem, “Changsha” is very important as it is of autobiographical importance to Mao’s very famous association with the city of Changsha in the Hunan Province of China.

Orange Island is mentioned in the poem. Mao spent a very long time as an adolescent on that island in the Xiang River in Changsha. He studied there at what may be the oldest library in China. He was schooled at an academy on that island, which made Hunan Province a very special place to Mao and to the whole of China. This academy dates back some 900 years. In other poetry he describes the tangerine trees, which gave the island its name. There seems to be some confusion between the tangerine fruit and the orange. The island is known for tangerines, but it is called Orange (according to Cao Fang – known as Kevin Cao, Chinese Director of the Confucius Institute at the University of Guyana). Mao certainly makes reference to the time he spent there and the occasion when he actually swam across the wide Xiang River.

The historic relationship between Chinese poetry and politics thus continues to be of intrigue and interest. It is therefore fitting that selections of classical poetry, and of the poetry of that nation’s esteemed statesman, who followed the classical style in his writing, be used to commemorate the occasion of Chinese Lunar New Year and the Lantern Festival which brings the holiday and festive period to an end. (This year, the holiday and celebration activities were very muted and curtailed because of the outbreak of the Coronavirus in China).