By Karen Abrams

While many educators are debating the merits of virtual education versus in-classroom education, very few are taking a holistic approach to the changes that are necessary in the entire education system. Within the past few decades, classroom education has consistently failed children who live in high-poverty neighbourhoods and this fact is not just unique to Guyana. The phenomenon is evident even in the United States as demonstrated in a comparison related to college readiness.

According to the ACT’s Condition of College and Career Readiness 2018 national report, only 11% of African-American children met three or more college-ready benchmarks in core subjects. Asian-American children whose parents tended to be highly educated immigrants ranked highest at 62% for college readiness in three or more core subjects, with 48% of white children achieving college-ready benchmarks in three or more subjects. The disaggregation of the African-American data reflects that children of African and Caribbean immigrants tended to score among the highest performers across all core subjects. This writer recognises the inherent limitations in comparing children of highly motivated immigrants with the entire pool of black and white children in the United States.

The time is right for the curriculum reassessment necessary to realise enhanced learning outcomes for Guyana’s children.

Nor should we become paranoid about pandemics. We must begin to educate our people about the likely future threats to global health and seek to erect defences against them as best we can. Since there is every indication that more, rather than fewer such maladies are expected in the future, we need to begin to bend our minds in the direction of building capacity to respond to them. Those nations that implement effective long-term strategies for crisis management and emergency preparedness in all areas, including education, will not only survive but thrive in the face of such challenges.

By 2050, 68% of the world’s population will be living in urban environments that feature highly concentrated spaces and these densely populated spaces could well accelerate the contraction and spread of diseases. Over the past decade we have experienced severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Swine flu, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), Ebola, Zika virus, Dengue fever… and now, COVID-19. It would be naïve to think that the buck stops here. The challenge, going forward, is for leaders to reimagine education. Access to virtual learning must therefore become inherent to the ‘new normal’.

Today, even in the United States, most schools have no coherent technology strategy. Where devices are available to students, these are not connected to a coherent teaching strategy. Less than a third of teachers in the US believe that education technology innovations have changed their beliefs of what schools should look like. Many technology administrators actively work to curtail any real progress in this area by implementing onerous and regressive network security policies which require their presence for every system change.

One such example we encountered was while attempting to install the Scratch Coding application for an afterschool STEM club, on a roomful of new computers at a local primary school. In pursuit of this objective we not only discovered that the system admin privileges did not allow for local installations, but that the Head Teacher had no idea as to what the policy was in relation to having the application installed and made available to students. After delaying the programme for several weeks, we managed to ‘solve’ the problem by bringing our own laptops. The irony here was that these laptops sat ‘cheek by jowl’ with perfectly working school desktops that were, in the circumstances, no more than proverbial white elephants. No serious twenty-first century education policy can live with these regressive policies.

Another issue which must be addressed with alacrity is access to internet and technology devices for poor students. We are now in a situation where the COVID-19 pandemic has already created a wider gap between those students who have access to virtual learning infrastructure and those who do not. Poor students remain at a significant educational disadvantage and this is not expected to change radically in the immediate future.

STEMGuyana’s immediate recommendation is for all internet hubs in Guyana to be reopened and staffed with the strict requirement that these follow COVID-19 health guidelines. While open, the number of students per session would be limited, systems would be disinfected after each use and protocols for social distancing, temperature checking, hand-washing etc, will be rigidly enforced. The reopening of the hubs will allow immediate opportunity for less economically fortunate students across the country to immediately access virtual learning opportunities.

Looking into the future, virtual learning will become a normal part of education systems and will be fully integrated with in-classroom learning. There is no question that both approaches bring significant benefits and that school systems must begin to rethink curriculum and educational strategies to make allowances for their coexistence. Virtual learning must be fully integrated into teaching plans. This means, of course, that teachers must be trained in virtual teaching techniques. Teachers must learn how to curate engaging and easy-to-follow virtual content.

Finally, it is important that schools shift the way they teach to reflect the new economy and to engage the 21st century student who has access to video games, social media, video content, and rapidly changing technology entertainment environments. The 21st century student must be taught how to manage his/her own schedule, how to apply content knowledge, and must demonstrate in this era of Google learning, that they have the ability to research and learn on their own.

Educators will have to decide whether there is more value in continuing to force students to memorise content which takes them significant time to learn, and which they soon forget, in an environment where employers value creativity, adaptability, collaboration, effective communication and emotional intelligence.

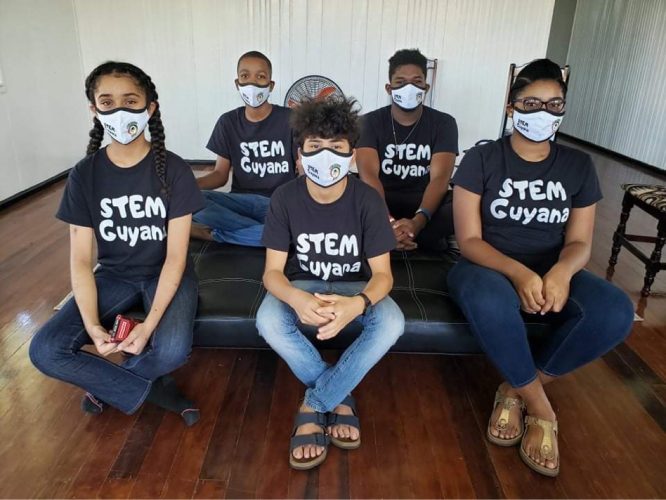

Today, students in virtual classrooms at the STEMGuyana International Summer Academy work in an environment with teachers from the United States and students from more than 4 regions of Guyana and 3 states in the US. This facility positions our 21st century students to meet and collaborate with students from around the world, an opportunity that will broaden their educational experiences and enrich their lives.

Karen Abrams is the Head of STEM Guyana