Although recently retired after giving over 40 years to the livestock sector, Pitamber Panday is still on duty for the farmers who need his help.

On the morning of a Holy Saturday interview with Stabroek Weekend, Panday, 62, a former livestock development officer tended to a calf with pneumonia in Vive Le Force then went to La Retraite where a cow dropped and came down with hypocalcemia. On Good Friday, he had tended to a cow that was injured in the eye and infected with worms. “I cleaned it out. I was just helping out. I will help as long as I have good health,” he says.

Panday, who became known to farmers during his work as ‘The Animal Doctor’ and ‘Uncle Vet,” said the mutual respect he enjoyed with farmers over the years kept him on the job in spite of problems ranging from inadequate transportation, inadequate staff to get the job done effectively, and poor remuneration.

“There is never enough staff. There were times when I had to function as livestock assistant, livestock officer and vet. During my time, I was given a government house next to La Grange Police Station where I lived for 20 years. Now they are giving a $30,000 for housing for non-resident personnel,” he noted.

In March, the Guyana Livestock Development Authority (GLDA) presented him with a plaque for his “stalwart contributions to the livestock sector” for over 40 years. But you could say he was born into the work.

Panday, although born at Annandale, East Coast Demerara, grew up in Mahaicony Creek as one of eight siblings.

On completion of his secondary education, he stayed in Mahaicony for about five to six years, helping his father, a cattle and rice farmer.

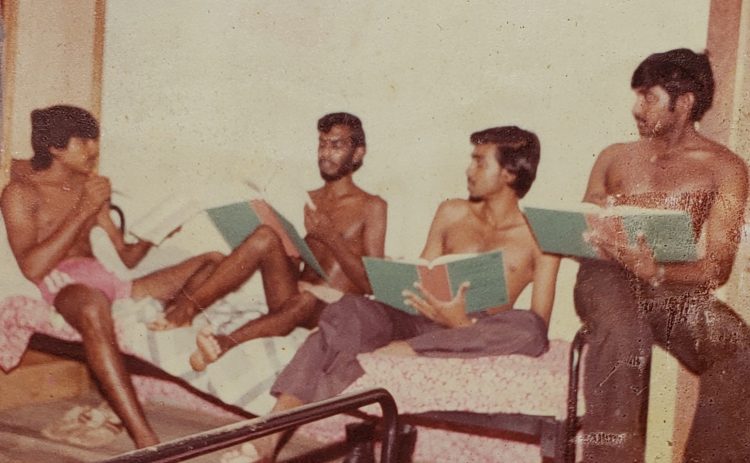

“One day I saw an advertisement in one of the newspapers calling on students and animal health personnel to apply for a scholarship to attend the regional residential institution, REPAHA (Regional Programme for Animal Health Assistants) at Mon Repos. It was one of the best institutions on animal health in Guyana. It catered for Caribbean students. They needed five Guyanese for a class of 38. I applied. At the interview, there were about 60 of us. When Dr Allan Fox, REPAHA principal, heard that I came from Mahaicony, he asked me about the problems we had with animals,” he recalls.

Panday told the interviewing panel that Mahaicony was a rice growing area and during the rice crop the animals would go into the rice fields, consume too much of paddy and end up with rumen impaction, which affected digestion causing the cows to get sick. He told them about the problems of birthing calves and mastitis or milk fever in cows and how they dealt with the problems.

“Dr Fox asked me if I would like to become a vet. Of course I said, yes,” he adds.

‘The Animal Doctor’

At REPAHA, which has since been disbanded, he said, “We were trained by the best.” After graduating, the Guyanese students undertook a two-month orientation at the Ministry of Agriculture in Georgetown after which they were assigned to various areas as livestock officers. He was assigned to the Essequibo Coast.

“I didn’t want to go to Essequibo because I didn’t know how to cook. I went to then agriculture minister, Dr Pat McKenzie and I told him about my plight. A few days later, he told me he will keep me at the head office.” At the head office, Panday said, he sat at his desk doing nothing and longed to get into the fields. One day, a colleague who graduated with him from REPAHA and who worked on the West Bank Demerara, died in a road accident. Panday asked to fill the vacancy created by his colleague’s death.

“I operated on the West Bank. Like in Mahaicony Creek, rumen impaction was a big problem as it was also a rice growing area. During mango season, the cows would also come down with acidosis from eating too much mangoes. In the beginning I had problems with transportation. You have to inspect most of the animals on site to treat them. Sometimes the regional administration would give me a vehicle for one day during the week. Farmers would put up a blue flag and you know which house to stop at. Sometimes, at the last minute, I would not get the vehicle and that would impact very hard on the farmers who were relying on the service. Many times farmers would get very upset with me.”

Then he bought a motor cycle. “For over ten years I rode the motor cycle to do my job. During that time people got to know me well. They started calling me ‘The Animal Doctor’.”

While he was still single, he recalls, some farmers would go to his house after work or on weekends and turn off his stove if he was cooking. They would ask him to take his kit and follow them. They would feed him after which he would tend to the animals.

After he married his high school sweetheart, he says, “They called me Uncle Vet and Uncle Cow Doctor and they called my wife Bibi, Auntie Vet and Auntie Cow Doctor.”

After ten years on the job, he was given duty free concession to buy a car. This made his work a bit easier.

Occupational hazards

In his work, he says, the poor people liked him and, probably, that kept him in the job for so long. “I knew what it was to be poor. To buy text books, my father sold young animals reducing their worth.”

Although his working hours were from 8 am to 4 pm, he worked round the clock. “Animals give birth at nights, too. Some births are difficult. Once a couple told me their cow had dropped that afternoon. At 1.00 am next morning they came for me to help them because another calf was coming. I had to go and assist them to get out the second calf. Sometimes cows give birth to twins and triplets. Calf birthing could be very difficult.”

He recalls that one rainy day he went to Sisters Village to deliver a calf on a muddy dam. “I took three hours to deliver the calf. Sometimes you have to go on your knees. This time I had to lie down to do that delivery because the cow could not stand up. When I finished I had to wash out the mud from my clothes in the trench to wear them again.”

In 2014, when he was in bed with a fracture he sustained after a cow had kicked him, he says, a woman farmer complained to him about the loss of a calf because the veterinarian who tended to the cow did not take out the placenta and the cow became ill. The vet did not look at the calf and it died of pneumonia. She believed that if Panday was there, she would not have lost the calf.

“These are poor farmers who need the assistance and can’t call a private vet. Some new staff would do what they have to do quickly and leave. One of the new staff accused me of spending too much time with farmers but I always remember Gavin Kennard, another minister of agriculture who had charged us, ‘to spend time with the farmers, show and teach them what you learn, and follow up.’ That charge has stayed with me.”

The cow that kicked Panday had hypocalcemia after giving birth. “They told me the cow was staggering and trembling. I went right up and gave it a tap thinking it was weak. The cow reacted with a quick kick that caused me to lose my balance and I fell heavily to the ground. I had to get surgery and some screws inserted in the bones to help the healing process. I was roundly criticized for getting kicked by a cow because of my years of experience.”

Beyond the call

“I have walked with almost every farmer in the backdam. Some of the young livestock assistants and vets these days would tell farmers to take the animals to them. No staff would do what I did. In fact, they attacked my method and say I trained the people bad.”

Farmers have their own problems, too, he said. Often it is difficult for them to bring out 20 cows or more from the backdam. “Not everybody got a tractor.”

A lot of what he did was voluntary, he says. “Even if I worked at nights, I had to go to work next day. There was no overtime. How many other staff will do that today? If a farmer has to build a chicken pen or a farrowing crate, I would go on weekends to show them how to build it. The farrowing crate is an enclosure in the pig pen to limit the movements of the pig that give birth so it does not crush the piglets to death.”

One Easter Monday when his two children were young and he was scheduled to take them to fly their kites, Panday said, there was a rabies outbreak on the West Coast. “A few farmers asked me to help vaccinate their animals. I returned home at 7 pm. My wife asked me if that was the time I was going to take the children to fly kite.”

In his work, he said, people have tried to bully him. Once, he said, a former high ranking regional official who seldom took advice, had some old cows and one of them died. He blamed Panday for the death and called for his dismissal.

“The biggest mistake the official made was to call Dr McKenzie and tell him I refused to go to the backdam. I don’t know what Dr McKenzie told him but I heard the official say that even though I was one of the most hardworking individual they had in the fields, I got him annoyed.” Panday gave the minister in writing, which he copied to the official, his version of what transpired. He remained on the job.

Now, in his retirement, he still remains on the job, advocating for farmers whenever the opportunity presents itself. “Livestock farmers need more land. I thought that when the government scrapped Wales Sugar Estate they were going to allocate land to livestock farmers and former estate workers. That is what the authorities told us and that is what we [told] them,” he explains.

Some farmers have their animals on the abandoned estate lands. “However, they cannot make pens to keep the calves safe, especially in the rainy season.”

Noting that Guyana was declared free of foot-and-mouth disease, Panday says, “We could rear and export meat to the entire Caribbean. Our governments are not serious about rearing animals. If you want sheep or pig farmers to produce well, you have to give them land. This country alone could supply the entire Caribbean with mutton, goat meat, pork and duck. Farmers are willing. Governments have to give lands to small and poor farmers too. Nobody is really helping them. If you are serious about livestock rearing and you want farmers to adhere to good management practices they got to have proper housing for animals and space is needed for this.”

“We, at the [GLDA] have been advocating for slotted floors for small ruminants. Slotted floor pens are elevated and built with wood and spacing so the pen will be dry and clean,” he adds.

Provision has to be made for heavily pregnant animals, animals in heat and for baby animals. “If you want to save animals, you got to have proper housing, and land is needed for this. Everybody is only talking,” he says.

When he is not still fighting for farmers, Panday says he enjoys his gardening hobby. “The only regret I have is that I lost my wife. We had planned to retire in Mahaicony Creek, live where the air is more oxygenated, and bathe in the creek as I did as a boy. I can’t go by myself anymore,” he adds.