By Claudia Tomlinson

Britain has a system of Pupil Referral Units (PRUs), which are over-populated with black children, those whose parents and grandparents are settlers from the West Indies and Africa. Its Youth Offending Institutions — prisons for young people before they enter the adult system — are overflowing with black and Asian young people. Many of these young people were earlier in PRUs; they were evicted from mainstream schools to await a destiny with adult prison. This is a pattern repeated globally in the Western world, with young black and minortised people facing a unique path, or pipline, from school rejection to prison. Explanations widely touted include notions of bad home life, bad genes, or bad luck. But a recent BBC television documentary, suggests that it is the behaviour and attitudes of the state that play a role in condemning black children.

Following the murder of George Floyd at the hands (or knee) of a white police officer in the United States last year, there has been a global upsurge in demands for racial justice for black people, in all arenas. Many institutions and organisations conducted examinations of their practice, and committed, for a period at least, to implement strategies and polices to redress these injustices. The BBC commissioned Small Axe, a television drama series directed by black Oscar winner Steve McQueen and screened on prime time TV. The series featured Education, the dramatisation of the black community coming together to fight the practice of wrongly labelling black children as educationally subnormal and placing them in schools for the educationally subnormal. A new documentary, Subnormal, A British Scandal, produced by Rogan Productions, was screened by the BBC in May, this year, and lifted the lid on some of the underlying truths of what happened to black children during this period, and its ongoing impact today.

Director Lyttanya Shannon, who also narrates the documentary, opens the programme with a number of fruitless calls to individuals who had been wrongly placed in schools for pupils considered educationally subnormal. Although she succeeded in getting three survivors of the system to speak, there were others who felt unable to share their story as they had kept it from their nearest and dearest due to shame and embarrassment. The three survivors of this system that spoke included Noel Gordon, an author and children’s educator, and now the proud holder of many qualifications, including postgraduate university qualifications, which he is seen as proudly displaying around his home. For Noel this is clearly a display that is about vindication and redemption of his destroyed childhood education.

The heart-breaking testimonies from the other two survivors, who bravely spoke out in the documentary, show how the system blighted the lives of black children for years. Social worker Anne-Marie Simpson was born in Jamaica and raised by her grandmother. She had missed several years of education in Jamaica due to living in a rural setting, with lack of transport meaning she simply couldn’t get to school. She joined parents and a family in Britain she didn’t know — and who didn’t welcome her arrival — and found herself rejected by her mother and siblings in her new home. This migratory trauma, a common experience of West Indian children in Britain, meant that she experienced emotional difficulties and ended up being placed in a school for educationally subnormal children. She survived to become a successful social worker.

Creative writer and graduate Maisie Barrett, who is also featured in the documentary, was also wrongly labelled as educationally subnormal and spent years in such a setting, where she was used to bathe and care for other children. It was only when her mother employed a private black social worker, years later, to assess her, that she was found to be of normal intelligence and permitted to go to a mainstream school. But she lost years of valuable education that she has dedicated her life to recovering, becoming a university graduate despite the system.

The stories of the survivors are interspersed with the stories of those who identified the issues and fought the system, against a torrent of denials of their arguments, or what might be called gaslighting today. Grenada-born Professor Gus John, a lifelong academic and community activist, sounds a warning at the start of the documentary: ‘we are building a time-bomb for ourselves, and one that is going to blow the whole bloody place apart’. A central figure in the fight against the educational authorities in the 1960s and 1970s, when this practice peaked, he draws a connection between what black people were experiencing at the time, and how this plays out in other arenas and over time. This was simply one among a multitude of ‘other racisms’, he explains.

At the heart of the community response were three prominent Guyanese individuals. There was the late Jessica Huntley, a founding member of the first PPP, People’s Progressive Party, in 1950. Comrade of Janet Jagan, Cheddi Jagan, and Eusi Kwayana, she made a highly appreciated contribution to the liberation of Guyana from British rule. Her husband, Eric Huntley, also a founding member of the original PPP, and official of the party who became a political prisoner of the British for leading protests against their repression after the overthrow of the Jagan government of 1953. After migration to Britain in the late 1950s, Jessica and Eric continued their fight for justice, and founded Bogle L’Ouverture Publications, a publishing company and radical bookshop, in 1966. This company was the first publisher of Walter Rodney’s the Groundings with My Brothers and How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, highly critically-acclaimed texts. They were educational activists who investigated, and challenged the treatment of black children in the British education system.

They fought against the bussing of black children to prevent schools being overwhelmed by black children, an

eventuality the education authorities regarded as ‘completely undesirable’, as one official stated in the documentary. They also fought against banding, the practice of stratifying children into high and low bands. Plans were uncovered by activists to place the majority of black children in the bottom bands.

Their compatriot, friend and associate in the community resistance is Waveney Bushell, who was born in Guyana, like the Huntleys, and travelled to Britain in the 1950s, to work as a teacher. She eventually qualified as an Educational Psychologist, possibly the first black person to do so in Britain, and she took part in this year’s documentary. She was part of the community network of the Huntleys, that also included Professor John, and others. She was a founding member of CECWA, the Caribbean Education and Community Workers Association, and sounded the alarm from within the system to bring awareness to what was happening to black children in Britain.

As an educational psychologist who had been a teacher in Guyana, Bushell found it inexplicable that large numbers of black children arriving in the UK were found to be educationally subnormal. She discovered, however, that the British educational IQ tests that were being administered to the children were culturally specific, and this was not accepted at the time. She argued and proved the case. The example she gave in the documentary is the list of English words given to newly arriving West Indian children to define. When they did not know what a tap was, Bushell knew the word ‘tap’ was not used in the Caribbean, instead the word ‘pipe’ was. The presence of a tap in the testing room meant Bushell was able to ask the child ‘what’s that’ and they said ‘pipe’ as they would know it in the West Indies. This, and many other examples, proved the cultural specificity of the British IQ tests.

Speaking after the screening of the documentary, Mrs Bushell reflected: “It happened so long ago, and its brought back memories of my own feelings of anger, of helplessness, of hopelessness and the inadequate way in which the leaders of the psychological services didn’t lead the way, rather than ridiculing the children.” They failed to take action to prevent ‘filling the ESN schools with black children’. Retired in 1989, Bushell has no doubt that “it’s the same today as it was, that these children from fifty odd years ago. She considers that ‘these days, they present problems of behaviour, and to me, these problems are the direct result of the wrong placement in schools”.

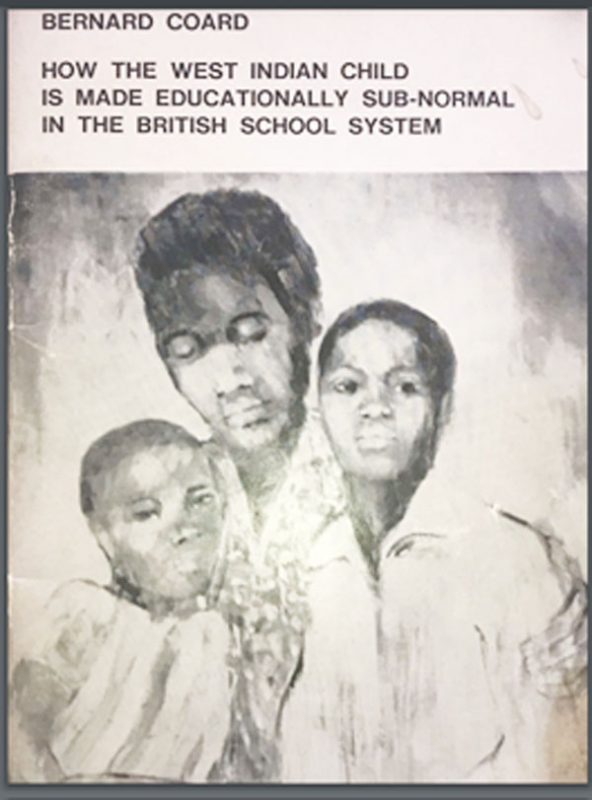

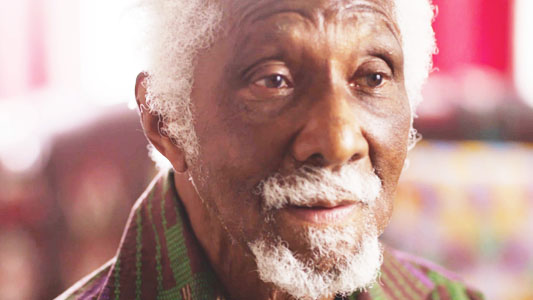

Bernard Coard, a young Grenadian postgraduate student, teacher and youth leader in London, was invited to CECWA and shared vital information with the group, who invited him to investigate further and present his findings at the CECWA conference in 1971. His findings were electrifying and led to the unmasking of the lies espoused by the education authorities. There was a systematic plan to wrongly place black children in educationally subnormal units, and take no action to remove them, even though it was known they were wrongly placed. Coard was pressured by the West Indian community to publish his work as a book. Through the considerable efforts of Jessica Huntley and John La Rose (whose company published the book), Coard researched and wrote How the West Indian Child is Made Educationally Subnormal in the British School System, which was then distributed widely among black parents, and teachers. Oppressed parents were able to look behind the curtain for the first time and learn what was happening to them, and how they had been deceived. The book received major publicity on television, radio and in mainstream newspapers, and has been a central part of the debate on black children’s education in Britain ever since.

Coard has continued to be recognised for his contribution to this major debate, both fifty years ago, and today. He does, however, hold a sense of disappointment about how little change has taken place, saying ‘it’s sad when you hear so many people tell you the same in every part of Britain you go’.

He is clear that his efforts were part of a mission for the Caribbean community, and not about securing personal accolades. He mentioned that one of Jessica Huntley’s best qualities was her ability to harvest the talents of West Indian intellectuals, such as himself, Andrew Salkey the Jamaican writer, and Ewart Thomas, the Stanford University Professor from Guyana, Walter Rodney and many more, for the benefit of black people in the community and everywhere.

The book cover was designed by Errol Lloyd, a young law student from Jamaica, who became a leading artist providing the images of leading radical books, including the Groundings with my Brothers, by Walter Rodney. He recalls being invited by La Rose, the co-founder of New Beacon Books, to discuss the book design, and the meeting was also attended by Coard and his wife, Phyllis Coard. He was given a copy of the manuscript and he produced a cover that depicted a caring black family unit as a contestation of the prevailing negative picture of these families in Britain. Lloyd said of the new documentary: ‘it is amazing that the book cover has been featured on a highly publicised television programme exploring the history of that period. It underpins the impact that the book had on individual as well as individuals bringing about change’.

Given the remaining vestiges of British and Western colonialism, particularly its anti-blackness stance in the West Indies and elsewhere, there is an ongoing need to understand the roots and origins of contemporary racism faced by black people in all arenas. This example of the systematic removal of black children from mainstream education, and condemning them to a life of underachievement, failure, and poor self-esteem, that many have spent a lifetime trying to overcome. This is a past that is very much in the present, not only in Britain but worldwide, and must be confronted for the benefit of all. Following the screening of this documentary in England, the British Psychological Society acknowledged its role in the past racist treatment of black children in the educational system, and highlighted that it had taken extensive action to ensure an inclusive and more diverse service. It stopped short of apologising for the harms. There is much work to still do.

Claudia Tomlinson is a researcher, writer, and campaigner, a Guyanese by descent, based in Britain. She is also currently a doctoral candidate researching the life of Jessica Huntley.