June is Pride Month. Throughout this month, members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Asexual, Interest and Queer communities and their allies – both in Guyana and across the globe – recognise, acknowledge, and celebrate the influences and achievements of the LGBT+ community through the millennia. These communities also use Pride month to highlight the problems they are striving to overcome both within their communities and within society.

There are many stories, both from and about members of the LGBT+ communities, which focus on the problems that they face: discrimination, inequality, violence, and the traumatic repercussions these negative experiences have on both individuals and the wider community. Sharing these stories are important because they can help people to understand and empathise with the struggles that LGBT+ people endure, thus aiding in their push for equality. Unfortunately, while there are stories out there about queer joy, success, innovation and growth, the trauma stories can often be prioritised, which reduces queer people to only their victimhood, without exploring the fullest extent of their humanity.

Simultaneously, Johnson lays out their manifesto by seeding their narrative with the vocabulary, historical and sociological contexts and explanations, and mental health coping tools so that their queer youth readers can understand themselves and their society while also protecting themselves, learning to cope with trauma and learning how to have agency over their lives and identities.

“In working on this book, I’ve brought to life a lot of stories involving a Black family dynamic that isn’t often talked about, a family that is queer-affirming while still learning about and navigating difficult spaces.” (p. 295)

There are three main things that stood out to me about Johnson’s book. Firstly, they wanted to show readers an example of a Black family doing their best to love and support the queer child in their midst. The sad reality for many LGBT+ youth is that their families often prefer to disown them, kick them out or even kill them rather than loving them for who they are.

I got a sense that Johnson harbours some amount of survivor’s guilt as they reflected on their family’s attitudes toward them and their other queer family members. “Why was my Black queer experience one of unconditional love when several others have become the standard of hate and familial violence?” they question. “How could one family get so write what the world has gotten so wrong? We should have been the rule. Not the exception.” (p. 138)

Throughout the book, Johnson details just how much their family supported them. For example, when their grandmother noticed that they were struggling to fit in and find friends at school, she started carrying them everywhere she went so that they could have company while learning business and life skills. Johnson’s older cousins were willing to get into fights to protect them. Johnson’s mother chose their Aunt Audrey, who happened to be a lesbian, to be their godmother, ensuring that they were able to have a queer-affirming support system around them.

Most importantly for them, however, is that Johnson watched how their family interacted with and accepted their transgender cousin, Hope. They detailed how their family discussed Hope as she transitioned. The family was not condescending. They just accepted Hope as she was, willingly adjusting their pronoun use and continuing to support her throughout her life. Johnson explained that seeing this acceptance and love gave them an example of what it was like to have a supportive community, and Hope gave them an example of how they could explore their gender and sexual identity safely so that they could settle on a label for themselves. All of these positive experiences helped to shape Johnson into the activist they are today.

“Masking is a common coping mechanism for a Black queer boy. We bury the things that have happened to us, hoping that they don’t present themselves later in our adult life. Some of us never realize that subconsciously, these buried bones are what dictate our every navigation and interaction throughout life.” (p. 31)

Unfortunately, one of the lessons Johnson learns the hard way was that their family’s love and support couldn’t protect them from learning and internalising the homophobia from the children and adults throughout their school years. Johnson explained that as a child, they were an effeminate boy who preferred the company of girls. By the time they were 10 years old, they were being called slurs by the boys in their school. While they were able to protect themselves from bullying through their competency in sports, their teachers and school administrators later made them feel unwelcome and uncomfortable. These lessons, which Johnson learns outside of their family, unite taught them to shut themselves down and pretend to be something they were not in order to survive navigating within spaces where their very existence was seen as offensive and threatening to the status quo.

When Johnson was leaving high school, they developed this urgency to leave home, move as far away as possible to escape the restrictiveness they associated with New Jersey. They thought that if they could go to a new place, they would be able to live their life authentically and freely. What they didn’t anticipate was the baggage they brought with them from the many masking lessons they learned as a child and teenager. “There was no magical awakening,” they reminisce, “There was no boost of courage that I thought would come with the fresh Virginia air. There was this boy who had always feared the consequences of coming out.” (p. 236)

Through Johnson’s writing about these experiences, they show that they carried the baggage of previous homophobia with them, which lead to depression and anxiety in school later. However, throughout these chapters, they showed how they dealt with these issues, found their communities, and came to understand that manhood is not a monolith and that they could define masculinity on their own terms to live their truth, define themselves and be happy.

“But the most valuable thing I hope this book will teach others, as it has taught me, is that there isn’t always a solution. That sometimes some things just end the way that they end. That some processes are always going to be an ongoing thing…But I have my story. The story that has now been told. So, if nothing else, we now have a start.” (pp. 295-296)

The element of Johnson’s book, and the one I appreciated the most, were the many snippets of advice they left in this memoir for their young readers and adults who may be caring for queer youth. They tell their readers about what it means to have agency over their names and decisions they make for their own safety, comfort, and happiness. They encourage them to find their own communities where they can feel loved and accepted. They talk about sexual abuse and assault and advise their readers that they do not owe their abusers empathy, but – if they can – they should hold them accountable. They advise parents and school administrators to ensure that their children get comprehensive and inclusive sex-education to prevent the harmful consequences of ignorance. Most importantly, through telling their family’s story, they show that it is possible for people to be loving, kind and just respectful to the queer people around them.

Johnson also talks about the complexity of “coming out” and how it’s not as simple as many people may think. They note that one misconception that both straight and queer people have about “coming out” is that you only have to come out once and it’s over. They disagree.

“Notice my confusion in how strong I was in some moments and how weak I was in others because that is what coming out truly is. It is not a final thing. It’s something that is ever occurring. You are always having to come out somewhere. Every new job. Every new city you live in. Every new person you meet, you are likely having to explain your identity,” they write on page 237. Through this quote, we get a sense of Johnson’s exhaustion of having to constantly explain themselves and having to decide whether coming out is safe or not, whether being their authentic safe can put them at risk of harm or not.

Lastly, and most importantly, Johnson admits that they don’t have all the answers, hinting that the reader has their own journey of gender and sexual identity to travel. Johnson’s memoir can only give them some of the vocabulary they need to navigate through tricky parts of their journey, but ultimately, everyone has to walk that part on their own. The most important thing they advise their readers to do is to educate themselves.

“The greatest tool you have in fighting the oppression of your Blackness and queerness and anything else within your identity is to be fully educated on it,” they say. “Knowledge is truly your sharpest weapon in a world hell-bent on telling you stories that are simply not true. (p. 104).

Conclusion

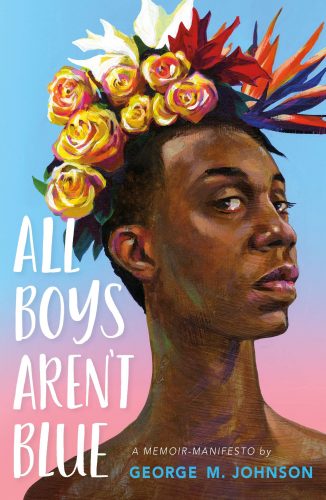

All Boys Aren’t Blue is a beautiful memoir that explores how families can support their queer relatives, and how, in spite all of that love and support, society can still beat queer people down and make them suppress themselves. Johnson candidly explores the pain of this suppression and how, through their journey to accept themselves and be free, they found peace and happiness and the tools they needed to heal some of the traumas they accrued over a lifetime. In doing so, they created a book which I would recommend for queer youth, because of the way it validates young people’s experiences and acts as a teaching tool so that navigate through their own journeys for self-discovery, healing, and social and mental health.

My rating:

Want more information about George M Johnson’s memoir? Scan the code below for an interview he did with Tamron Hall.

Want to read more LGBT+ books for pride month? Here are my recommendations:

Felix Every After by Kacen Calendar

The Henna Wars by Adiba Jaigirdar

We Are Totally Normal by Naomi Kanakia

Darius the Great is Not Okay by Adib Khorram

The Other Side of Paradise by Staceyann Chin