After he left primary school at Aishalton, South Rupununi, Tony James AA aka Chief, Kokoi, Toshao and Chief of Chiefs, was not certain what he wanted to do in life apart from riding horses.

“My passion was to be on a horse’s back all day long. I grew up among horses, enjoying the fresh air of the savannahs, running down deer, fishing along the creeks and rivers. So in a way I was unbridled in my love of nature and the environment,” James told Stabroek Weekend in a recent interview.

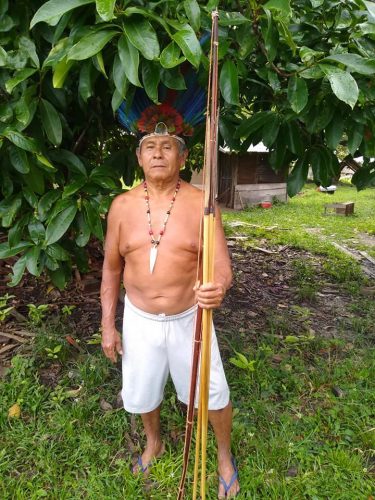

Given the name Kokoi, meaning visionary in the Wapichan language, by a late elder, Simon Marcello, James who is now 65 years old, said he taught for a week at Aishalton Primary. He then joined St Paul Seminary in Plaisance to see if the priesthood was his calling but dropped out after two years.

James was born in Aishalton to a Wapichan father; his mother was an Atkinson of Lokono (Arawak) origin from Moruca. “I lived between my mother and father’s home, my grandparents’ home, and Henry Winter who was the toshao for a very long time,” he said. From them, I became aware of my identity as a true Wapichan and learnt the Wapichan language. Most of the cows and the horses I got were from my father, grandfather and uncle Henry.”

James later got married, had four children and became an Indigenous rights activist after dallying in governmental politics for a brief period between the mid-1970s and early 1980s. “My father was a teacher and he wanted me to teach but teaching was not for me,” he said. “I was a district coordinator under the PNC government during the Forbes Burnham administration. During that stint, I found out that politicians are polished liars. I resigned because I could not lie to the people all the time and I could not fool all the people all of the time.”

After he resigned, outgoing toshao Christopher Duncan asked him to contest the village elections. He was hesitant but gave it a try. “I decided to become a toshao. Until today I have never turned away from the role of being a toshao or a leader of the community,” James said. He first became a toshao in 1982 and served for six terms.

A good listener, he poured the knowledge and experience gained from his previous work and studies at the seminary, into his job as a toshao and then later as a leader with the Amerindian Peoples Association (APA). “I learnt both good and bad from the political side. I used that to my advantage,” he said.

Years ago, he said, councillors came together to do things for the welfare of villagers without controversy and mainly because they were not politically influenced. “The community was much more united than it is today,” he declared.

As a toshao, he said, he began the August Games which eventually turned into the national heritage celebrations. “I suggested to Teacher Adrian Gomes of Maruranau to preserve our way of life. Bringing the communities together, eventually led to the formation of the Region Nine Toshaos Council (RNTC), which came into being long before the National Toshaos Council.

We carried the August Games to St Ignatius and then it filtered to the national level when the September heritage celebrations came. I took some of my experienced carpenters from Aishalton and we built the first benab in St Ignatius,” he recalled.

The drinking competition was never a part of the heritage celebrations, but like everything else, he said, there is an origin.

When the August Games started, he said, a resident, George Perry, was the only man left who had the art of regurgitating parakari (an alcoholic beverage made from the cassava root) like a spout to a distance of about ten to twelve feet, so as not to get drunk. This art was linked to the parakari dance. Perry was supposed to show off his skill at one of the first August Games but on the appointed day he indicated he was unable to do it.

“We already had the drinks prepared. What were we to do? I suggested that the toshaos hold a drinking competition,” he recalled. “I had the malaria. Lucky for me there was a councillor Matthew Aguilar, who represented me and won the competition. That’s how the drinking competition began.”

James wants a national holiday in honour of Guyana’s First Peoples. “I had recommended 10th of September in keeping with Stephen Campbell’s day. People who came long after have national holidays,” he reasoned.

How politics destroyed villages and RNTC

“I was elected chief of chiefs after Toshao Eugene Isaacs of Toka, the first chief of chiefs. The RNTC was a very vibrant organisation comprising all the toshaos from South Pakaraimas, North Rupununi, Central Rupununi, South Central Rupununi and the Deep South Rupununi including Wai Wai territory in Masakenari, until politics destroyed our institution,” he said.

“Politics are destroying our villages. Party politics blatantly infiltrated the most recent village council elections. It started a long time ago. Don’t try to force us because of political priorities on your part. Recently we had a PPP/C MP coming around and telling people they have to have a PPP toshao. If you doing a self-help project, you calling everyone. You not going and invite PPP people alone to do village work. Party politics has its time and place.”

The RNTC was a powerful group interested in having a resolution to their land issues. James said, “The government of the day fought us down. They targeted individual toshaos and started to break us up at the individual village level. It became intense and after new elections, new toshaos and new councils came in and many were politically affiliated. Most toshaos now cannot rally the community behind a common objective.”

Although there is no RNTC at present, he said, the framework is still there. “We didn’t ask the government to recognize us. It was our idea and our way of thinking to determine our future for the future generation.” Nevertheless, he said, “I continue speaking and training. Right now I am part of the South Rupununi District Council which considers me an elder. I am not a lawyer. The advantage I have is that I can speak the Wapichan language fairly well.”

Throughout his years of activism, James said, he has been in the struggle for the legal recognition of ancestral lands in keeping with the 1969 Amerindian Lands Commission Report for South and South Central.

“I have been able to get people to understand that this is not Tony James’ idea. This idea was born even before independence. If you look at the 1969 report, you will see that the then toshaos who identified our territories, never went to school, did not know to read and write, did not know about maps but they could have identified the territory by landmarks, rivers, mountains, etc. That is what I have been passing on to the new toshaos and new councils all the time because we cannot afford to give up our territory to be destroyed,” he said.

Activism

When James joined the APA his first meeting was in Boa Vista involving representatives of indigenous peoples from Brazil and Venezuela.

“That was where I first heard of the issues affecting the Indigenous Peoples in Brazil and Venezuela in terms of mining and logging among other social and economic issues. I knew that

what was happening with our neighbours would eventually reach our communities. That is what drove me to where I am today,” he noted.

Speaking of the illegal mining taking place at Marudi Mountain, he said, “We are now fighting for our territory. It is not like we suddenly get up one morning and think that that is our land. All of this was in the 1969 Amerindian Lands Commission Report.”

Marudi is within the extension of Aishalton and is seen as Wapichan territory, he said. “What is happening right now is a complete violation of our rights. We don’t have control of who is coming in or who is going out and what is going out and what is coming in,” he noted.

He said it was a violation of their rights under the constitution which clearly recognises the rights of Indigenous Peoples to land and security and to their promulgation of policies for their communities.

“What they are doing is destroying our way of life, our culture, our languages, our healthy lifestyle. They are pouring in mercury, contaminating the ecosystem in the entire environment. The constitution speaks to everyone having a right to a healthy environment. Living is making sure that the environment is healthy, so that everything will be healthy. The people, the air, the water, the fish, the food chain,” he noted.

When former president David Granger visited Aishalton to open a radio station, James gave him a map indicating how the pollution of the waters from Marudi could reach the Atlantic Ocean and affect every community that lives along the Rupununi River and the Essequibo.

A survey of mercury contamination of four communities in South Rupununi, he said, showed high levels of mercury in women in Parabara who are affected by mining along the Kuyuwini River where the water flows into other creeks and rivers.

“The Parabara people used to catch haimara, salt it and sell it to make a living. Now no one wants to buy anything from Parabara because we know that the fish are mercury contaminated,” he said.

The violations were documented and submitted to the previous PPP/C government, the APNU/AFC government and now once again to a new PPP/C government.

“I don’t see any political will by any of the governments to want to resolve the issue of land rights for the Wapichan people. If we were able to get legal recognition for the land we are thinking about, we would have been contributing to the preservation of the environment for Guyana and the world. The recent spate of floods. Isn’t that a clear indication that climate change is real?” he asked.

“The environment, the forest and everything else is our education system, health system, supermarket and playground. If we don’t plant a stem in the ground, we will go hungry. Our culture is so interlinked to the environment.”

Of the government’s intention to give more land to miners in the area, James asked rhetorically, “What do you think is going to happen there? It is having a negative impact on our community because Aishalton and Karaudarnau are the two gateways into Marudi. We have our women folks being fooled and left as single parents. We have murders. Now we have cases of drugs affecting young people in the villages. We have prostitution. We have Spanish-speaking people and Brazilians there. We brought these issues to the attention of GGMC officials but to date nothing has been done. Even with the Covid-19 pandemic they are in and out and they cuss up our people when we put a gate to try to safeguard our people.

“Our communities are being raped. Our environment is being raped. Our way of life has been raped and our rights that are enshrined in the constitution, nobody has regards for that.”

Noting that last year, the authorities were encouraging people to go into Marudi, James said, “We stood up against that. If we are able to control this area in collaboration with the authorities, we can contribute to the Paris Agreement and other agreements that Guyana has signed on to in terms of climate change and sustainability.”

He noted that Marudi mountain is the source of all freshwater flowing to the Atlantic Ocean in the north and into the Takutu River which flows into Brazil in the south.

Being President of the APA, he said, comes with threats. He first served as its vice president and then as president for several years. “I consider myself a fighter and I will throw the last punch before I leave this earth,” he added

In father’s footsteps

Three of James’ four children have become human rights activists. His sons Kid and Rawle are both involved in Indigenous rights activities and are affiliated with the APA.

His daughter, Faye, is a women’s rights activist who works with the South Communities Indigenous People’s Association (SCIPA) and his last son Anthony, is a teacher.

“While I am happy that my children have followed in my footsteps, it is unfortunate I have not taught them the Wapichan language. They always blame me for that. I grew up in a home where I was beaten for speaking my language. My father was a teacher and my maternal grandfather, Salvador Atkinson, was the first headmaster here. I got away from my parents and went to my paternal grandparents who were real Wapichan people. I went into the balata bush and I learn to speak the language from them. Nobody can fool me,” he said.

When Covid-19 hit, he said, “We remembered the medicinal plants which is part of our culture that is being destroyed by the quick money made by mining, prostitution and illegal activities.”

James is a diabetic having been diagnosed 22 years ago. When he tested positive for the coronavirus, he thought he was going to die. A drinker of herbal teas, he said, the most he experienced was a slight headache and a slight loss of taste. He believes that medicinal herbs helped him to recover. At the time he was not vaccinated.

Apart from receiving the Golden Arrow of Achievement, James was also recognised for his activism by the former Ministry of Indigenous Peoples Affairs.