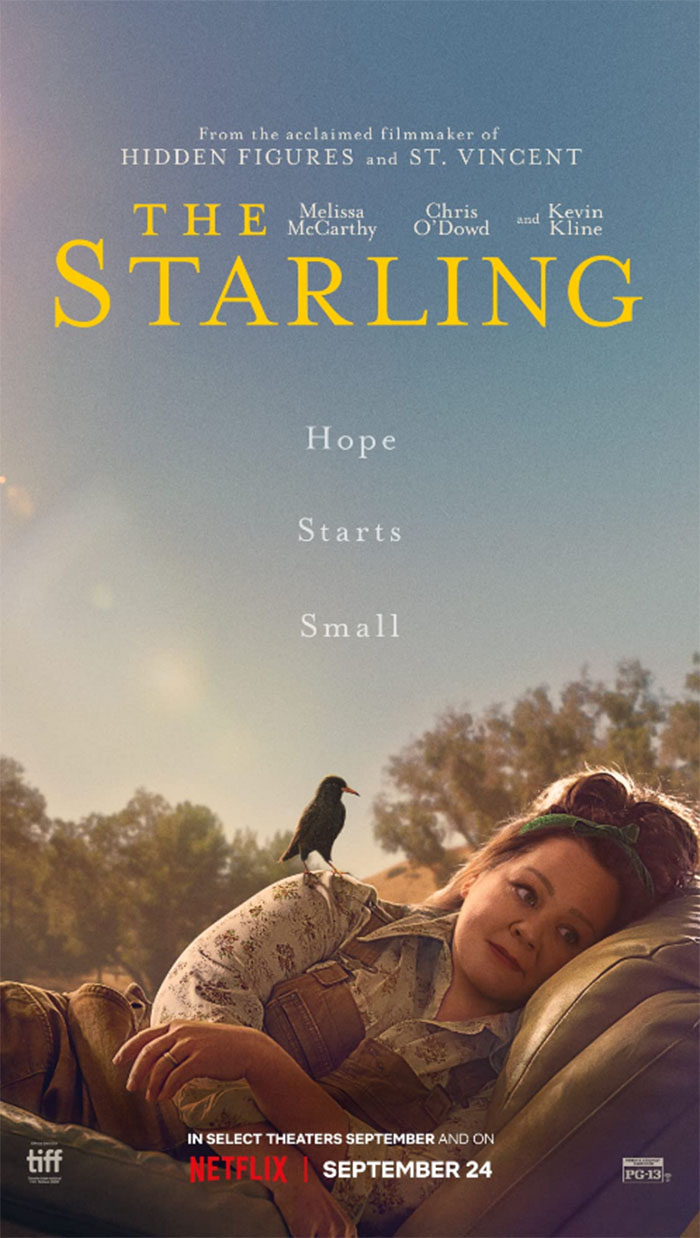

The newly released comedy-drama “The Starling” is the second underwhelming Netflix release starring Melissa McCarthy this year, which is a disappointing fact for such an engaging actor. Yet, the problems with “The Starling” are not the same ones that plagued the abysmal “Thunder Force” earlier this year. Where “Thunder Force” was so inconceivably senseless that its cast of talented performers seemed incongruous with its quality, “The Starling” has clear motivations that immediately identify the attraction of those involved. It means well. But good intentions can only take you so far. And with, “The Starling” far isn’t enough.

More than anything, it’s a story about grief and healing – a noble goal. A married couple suffers the crippling loss of their baby to SIDS. The husband (Chris O’Dowd as Jack) is checked into a mental hospital after a tragic reaction to the death, while his wife (McCarthy as Lilly) remains at home but regular visits to him. This is, in theory, a film about the two of them struggling to make their way back to each other. Except it is not, not really. Or, not always.

We spend more time with Lilly, so we might say it’s really about her struggle to make sense of the dualling responses to the tragedy and finding a way to understand her grief and her husband’s detachment. Except it’s not really that. Not completely. It’s kind of a story about Lilly’s relationship with a psychiatrist turned veterinarian (Kevin Kline as Larry Fine) who Lilly seeks out, reluctantly. And yes, it is that – for some time, at least. But the title of the film, and the thing the script seems to be depending on for momentum is a bird. That starling. This is “The Starling” after all.

The starling is a pesky bird that takes nest in Lilly’s yard. It harasses her, it frustrates her, it angers her and then finally it helps her to reach some understanding about her grief. The bird, like many things in “The Starling,” is a symbol. If you said that sounded literary, I would agree. I could imagine a very sharp, and tender, short-story about this incident. Except, this is not a literary adaptation. This is an original screenplay, and the symbolism feels more effortful than organic. It’s not that Matt Harris’ script or Theodore Melfi’s direction are careless. We can sense that they care. You can see the empathy and emotion eking out. It’s there in the beats that linger, offering moments to the patients and the staff at the hospital with Jack. It’s there in the ambivalent way the script finds moments for Lilly’s employees, or the pet-owners that approach Richard. Yes, it will argue, these people are sad or lonely or worried or strange or odd and it’s all pleasantly diverting enough but the more “The Starling” goes on, the more it feels incredibly unformed and structureless and easy to ignore.

“The Starling” is so committed to its engagement with symbolism as a concept it elides the critical value of engaging with these themes as film, as something that depends on images and light and movement and composition. There’s a moment late in the film that puts this into perspective. In a fit of pique, Lilly finds a ladder and climbs a tree to seek out her flying foe. The relentless score picks up, jauntily at odds with her headspace. She climbs the ladder, the sun lighting everything in something that feels beatific and out of place. She sees a nest of birdlings, nestled in between a baby booty. It’s a moment of intense emotion. Or it should be. And then she falls. We watch her lying – limbs spread out. The soundtrack plays “light-hearted music” (as per the captions) and I found myself confused. There’s a rupture in the film there. The language of the scene feels incongruous from moment to moment. What does it want us to feel? What does it want us to think? There’s ambiguity and then there’s this strange hodgepodge of emotions in “The Starling”.

From scene to scene “The Starling” feels unsure of what the stakes are or what it wants from its audience. This kind of rollicking ambivalence might work in a film that had a clearer through-line but the offhand approach feels counterintuitive and frustrating more than illuminating. Everything is covered in a sheen of pleasant niceness that’s diverting enough to watch but is so disengaged from any real tension, or crisis or catharsis that when we hurtled to the very end and a resolution that felt all too trite, I didn’t realise it had ended because it all seemed to be going along so placidly.

“The Starling” is so preoccupied with being nice, it forgets to be good or meaningful or thoughtful. McCarthy is offering an open-faced approach to grief, and O’Dowd is bolstering where the film is not. In fact, the performers are uniformly dependable, doing their best on the edges. Lorretta Devine, doing the most with a nothing character as a patient; a charmingly detached Timothy Olyphant as Lilly’s boss; and Skyler Gisondo, who might be a really interesting actor as his career goes. But, it’s all incredibly schematic and limp. In a way it makes the film feel more disappointing. Everyone here feels like they want to be here, they want this to work but “The Starling” just doesn’t’ work. It’s too unambitious without the guts or temerity to dare for more. It tides you over but none of the emotions linger for days or hours or even minutes after. And for a film that’s substantively about grief that feels like a betrayal more than anything.

“The Starling” is streaming on Netflix.