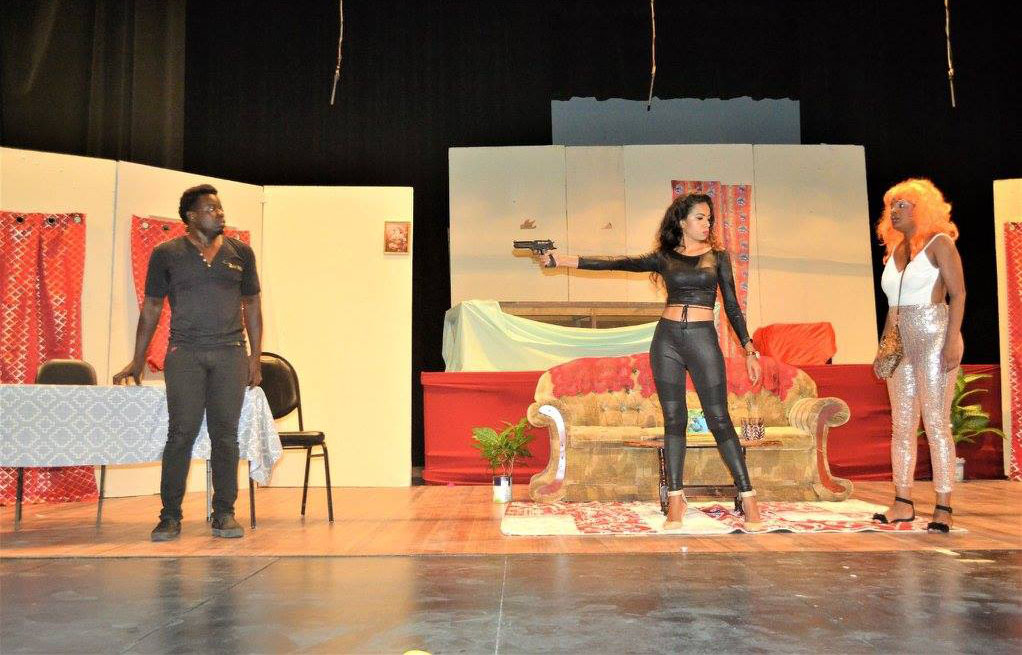

It was through that medium that a concern about Guyanese drama was raised by Francis Quamina Farrier, which provoked responses from Henry Mootoo, Dave Martins and others. Farrier, a veteran Guyanese dramatist, playwright, journalist and videographer, complained that there was a prevalence of plays depicting gun violence on the Guyanese stage. It was disturbing, he argued, that so many plays dramatised gun play, with particularly young women pulling guns in response to sometimes unlikely situations. He found the credibility of plots questionable and the suggestions and likely influences frightening.

Mootoo joined him in those concerns, commenting that there were endless other creative possibilities for young playwrights, and they ought to be led away from the concentration on gun violence and towards scenarios that portray the upliftment of the society. The critics of this development on the Guyanese stage feared the kinds of messages that were being given to the public, the possibly corrupting influences on the society and the impact on the minds of the youth.

How true is that as a picture of contemporary Guyanese drama? Is it so frightening a trend as expressed in that dialogue? And is it really something to worry about?

There has been very little development in drama in Guyana over, perhaps, the last five years, and across the Caribbean over the last two. The latter is mainly because of the general shutdown forced by the COVID-19 pandemic; Caribbean theatres have been closed since March, 2020. Causal factors in Guyana include the absence of the National Drama Festival (NDF) since 2017. Exceptions to that stasis have been Carifesta, to which Guyana took drama in 2017 and 2019, and the National School of Theatre Arts and Drama (NSTAD), which has remained a catalyst to theatrical development.

Quite noteworthy was the Department of Culture’s dramatic performance presentation on national TV, in December 2020. That public showing of “Dramatic Distancing: Theatre Without Walls”, was the outcome of a mini festival produced by the NSTAD in the absence of the NDF. The entries were very short plays recorded on video, representing a creative way of producing and performing drama without violating the safety regulations forced by the Coronavirus. What was significant about the entries was that they suggested a minor advancement in stage action — creative responses to the prevailing conditions. The main themes across the board were based on the COVID-19 and its social aftermath. Where it wasn’t the main plot, it formed the base of other plots. The most important observation was the way the social environment drove the theme and the focus of the mini dramas.

However, going back several years – over the last decade, to be exact — there were a number of new plays, mostly one-act, with a notable prevalence of guns and gun violence. It is true that guns are frequently drawn on stage, but the reaction to it cannot be too hasty or emotional. The gunplay is part of a larger issue.

The modern Guyanese stage has been dominated by Realism going back 40 years. Realism is a form of drama that is a manifestation of the theory that plays reflect the natural environment. That has been the case in Guyana.

New plays by new playwrights have rapidly emerged in recent years, driven by a number of stimuli. These included a major workshop sponsored by Merundoi (the producers of radio drama), one-act play festivals at the Theatre Guild, the NDF, the NSTAD, the integration of Secondary Schools into the NDF, and a few theatre workshops. These drove participants, entrants and students to develop new short plays. These were mostly minor plays – the results of playmaking exercises and entries in the competitions, but there were also the work of dramatists at the national level, such as Mosa Telford, Sonia Yarde, Tashandra Inniss, Melinda Primo, Rae Wiltshire and Ayanna Waddell.

A number of common themes, plots and issues dominated what emerged. These included rape, domestic violence, suicide, human trafficking, and murder. Dramatic conflict was deeply explored with sensational reversals in surprise twists and shock endings, many of which were tragic. There were also deeper examinations of prevailing social issues which interested major playwrights around the Caribbean. At the time, the region was still coming to terms with realities such as homosexuality, lesbianism and HIV, some of the best dramas emerged to examine them. These included What About Eve, and Basil Dawkins’ Uptown Bangarang, both of Jamaica, as well as The Final Truth? by Thom Cross in Barbados and Richard Raghubarsingh’s Mary Could Dance in Trinidad.

These trends in the Caribbean tend to reach Guyana somewhat later than usual, and so many new plays caught on to serious examination of issues. The general tendency was to play for sensationalism, to thrill or shock the audience. Where same-sex issues were concerned, Guyana was slowly coming out of an era where these were subjects for humour and light treatment, or even horror. Some of the plays reflected the mental state of the Guyanese society to these developments; the population was slowly appreciating them as part of society rather than as social problems. However, problems still existed in the wider society’s non-acceptance of the presence of these human phenomena.

Playwrights seemed interested in the dark side of human existence, but they took their plots and themes from real problems in society. Suicide has been a major issue, and several plays presented characters who leaned that way when they found themselves caught in personal dilemma and social conditions. In similar fashion, domestic violence was reflected in several plays.

Arising out of these developments was an overwhelming number of new dramas in which guns featured. A favoured weapon in much of the stage violence, this ran parallel to the rising plague of illegal guns in crime in Guyana, as well as in private hands.

There were concerns that such plays publicly performed would have a negative influence on the society, particularly on the youth. The great irony in this is that many of these plays have been written by the youth. These social ills form the plots, themes, issues and conflicts in plays entered in the drama festivals by secondary schools. The students, having recognised the ills plaguing the society, chose to address them on stage. Therefore it is society itself that has generated the ills which are influencing the youth, and not the plays.

The portrayal of guns and the other social issues on stage must be placed in context, which is that that society has already negatively influenced what is being reflected there. The students and the playwrights are attempting to right those wrongs through theatre.

It is the business of the theatre to analyse society with a view to creating change. These plays are mirroring social behaviour. Will they influence change and resolutions? It can be said that the prevalence of guns on stage is a mirror for society to see and hopefully change itself. If one is fearful of guns on stage, one needs to be fearful of the bigger contributing issue: the presence of guns on the street.