When you live in a country and city infested with garbage, after a time you learn to unsee it because to continually have to do so might turn you insane. However, foreigners arriving here are often struck by the sheer filthiness of the place and mystified that such a simple task as keeping a country clean is beyond the government of the day.

We hear each week of some delegation of investors flying in for high level talks and reports of promising infrastructure projects. But as they travel to and from the incomplete airport and their hotels, avoiding the potholes and the stray animals they must gaze out of the window and conclude that this is a very poorly run society. And they probably think, if this government cannot do the simple things why would I risk my money here?

Sixteen months into this administration not one major foreign-funded project has broken ground, be it public or private. All the talk of hotels, deep water ports, super highways, the Demerara Harbour Bridge are still mirages, computer generated images for the front pages of the state- aligned newspapers. Why on earth are all these investors hesitating given the glorious opportunities for riches?

Perhaps it is simply structural. Guyana is a miniscule economy, its population not much bigger than Nottingham, England with a fraction of its GDP. And unlike that city which is fully integrated into the UK economy, Guyana is cut off from its larger Latin American neighbours. So our smallness and isolation are impediments for some investors who do not see the scale required for adequate returns. However this is balanced by the prospects of oil revenues and sharply increased economic activity some of which we are already seeing but which is contained within that sector.

Many surveys talk about the ease of doing business here, or lack thereof, and the numerous agencies one has to navigate to get the necessary permission to start operations, and how they don’t communicate with each other and take their sweet time. This all might be true but is not necessarily an impediment for any serious investor. There is a need for bureaucratic checks on investment for financial and environmental reasons and all countries have them. A more significant factor is the element of discretion. Examples of this abound, be they building per-mits as part of outdated and vague zoning regula-tions, tax exemptions or whether the Environ-mental Protection Agency needs an Environmen-tal Impact Assessment or not. There seems to be little rhyme or reason and perhaps that is how the powers that be prefer it; areas of discretion are where politicians like to operate. This might be fine for a local businessman who can “phone a friend” but legitimate foreign com-panies are not going to spend millions based on a nod and a wink over drinks. Nor would any major publicly owned US company consider “emoluments” for fear of prosecution by their own authorities under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

A major contributor to what looks like the current investor hesitancy is the uncertainty over impending local content legislation, its proposed schedules and regulatory framework. While the private sector is naturally pushing hard for local content, foreign investors still do not have a clear picture of how the reality of this will be on the ground. If legislation is passed it will inevitably mean added costs for all companies as they create departments to ensure that each project has the requisite locally sourced material and local workers. Some companies may simply see the local content schedules as too burdensome and unrealistic, so rather than risk breaking the laws of a foreign country will curtail or not initiate projects here. This might explain why no large American firms are yet to show interest in any big infrastructure projects. After over a year of back and forth on this issue, it is high time the government brings what it has to the Parliament, and investors can decide if they should stay or pack up and go. Then we will see whether this approach spurs development or strangles it.

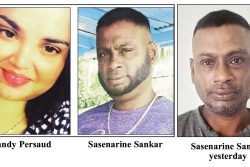

Finally, companies carefully consider all risks when making investment decisions including political risk. In that regard Guyana still remains a frontier territory and it is the primary cause for our lack of economic progress since independence. Unfortunately despite all the bluster of the past year about a New Guyana the political landscape remains remarkably unchanged. Public servants agitating for increases? Extra judicial killings? Rising crime? Accusations of an arson campaign? The encourage-ment of private and heavily armed “security services”? Large drug busts for which no one is arrested? Dodgy contract awards? And the ever present chronic political dysfunction and racially based discord? It is eerily reminiscent of the early 2000s although we are thankfully not at Phantom Gang level quite yet.

President Irfaan Ali has overseen and contributed to this regression by his refusal to hold consultations with the Opposition Leader which is a violation of his constitutional duties and a personal political failing. If the President really wants to launch this economy then he must face and solve his political problems and by doing so assure all investors that he can deliver a level of political stability they can live with.

If we don’t change the politics, then the garbage, the chaos and uncertainty will remain and we will muddle along as we have always done, because what is glaringly apparent is our poverty was never, and will not be, a result of a lack of money.