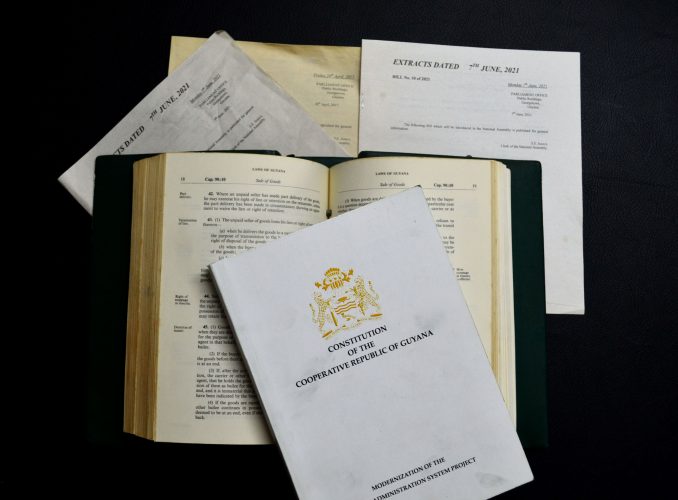

In accordance with its Article 8, it is the Constitution which in Guyana is the supreme law, and by which any other law which stands in contravention thereof is voided.

Over time, there have been numerous instances of Acts of Parliament and subsidiary legislation coming into direct conflict with the Constitution and having had to be struck down by the Courts because of their inconsistencies.

Such occurrences underline calls for laws to be reformed—be it constitutional or otherwise—and would no doubt bring into sharp focus what would be considered the most important role of a Law Reform Commission (LRC) in this regard.

In an invited comment, attorney-at-law Kamal Ramkarran opined that “the existence of a Law Reform Commission which has the responsibility to take a hard look at all our laws to bring them up to date should go some way towards correcting this situation…by the recommendation of the amendment of various laws which conflict with the Constitution.”

Attorney Teni Housty to whom this newspaper also spoke, underscored the value in ensuring unified laws, but noted the existing difficulties presented by laws which would have been retained from the colonial era, through the saving-laws clause.

On this point he emphasized that the Constitution must be viewed as a ‘living, breathing instrument not stuck in time.’

There have been numerous cases over the years which have attracted the attention of the Courts which have had to repeatedly declare the supremacy of the Constitution and strike out laws which violated its sacrosanct provisions.

In recent times, three such cases of notable importance have come to the fore.

The first was one brought by the transgender community which challenged the law criminalizing cross-dressing. The second was an action filed by a retired judge who challenged the exemption of the Chancellor and Chief Justice from the payment of taxes; and the third is an appeal currently before the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ).

In the latter case, Marcus Bisram is challenging the ruling of the local appellate court which overturned a decision of the High Court quashing an order of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), directing that he stands trial for murder.

His contention is that Section 72 of the Criminal Law (Procedure) Act which gives the DPP that power, is in direct contravention of Article 122 A (1) of the Constitution which provides for the independence of the Courts.

Bisram argues that Section 72 is on a “collision course” with the Constitution and for that reason ought to be modified or repealed; while also noting that it violates his rights to a fair trial as guaranteed in Article 144 of the Constitution.

Regarding the cross-dressing case, the CCJ in 2018 ruled in favour of a group of trans-women who had contended that Section 153 (1) (xlvii) of the Summary Jurisdiction (Offences) Act contravened their constitutional right to protection from discrimination in Article 149 (1) of the Constitution—freedom of expression as provided for in Article 146—and equality before the law as provided for in Article 149D (1) of the Constitution.

Meanwhile; the third case cited surrounds the most recent judgment where the High Court ruled in favour of retired Judge William Ramlal, that Section 13 (a) of the Income Tax Act contravened Article 149D (1) of the Constitution as well, in so far as it conferred tax exemptions on the Chancellor and Chief Justice only and excluded other judges of the Supreme Court.

Noting that there had been no legitimate aim to substantiate the differential tax treatment, the Court declared section 13 as amended by Act No. 7 to have been unconstitutional, void and of no effect.

Justice Ramlal had challenged the deduction of millions in income tax from his salary, which he described as discriminatory because of exemptions granted to the Chancellor and Chief Justice.

What all three of these cases have in common, is the violation of the Constitution by other laws—Acts of Parliament.

Article 8 of the Constitution provides, “This Constitution is the supreme law of Guyana and, if any other law is inconsistent with it, that other law shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.”

While this is widely known, the fact that the Courts are still being confronted with such matters, is indicative of the mammoth work which besets the LRC.

In keeping with the ruling of the CCJ, following the passage in the National Assembly of the Bill back in August decriminalizing cross dressing, Attorney General (AG) Anil Nandlall SC emphasized that the Constitution is supreme; noting that where it is found by the Courts that a particular law is inconsistent with the Constitution, that law can no longer be enforceable and would have to be vacated.

Meanwhile, Ramkarran expressed the view that the role of the LRC is far more efficient than using the Courts to bring legislation into compliance with the Constitution, since “litigation happens in a piecemeal manner when people are affected by certain laws and litigation is inherently unpredictable.”

Another notable case currently before the Court is the action filed by the Guyana Teachers’ Union (GTU), the Guyana Public Service Union (GPSU) and umbrella body the Guyana Trades Union Congress (GTUC), which are all contending that former President David Granger acted outside powers conferred under Section 21 of the Public Health Ordinance when he issued the first COVID-19 emergency measure back in March, 2020.

One of the key issues likely to come up for consideration is whether his exercise of powers under Section 21, were in keeping with his powers under Article 111 of the Constitution.

The contention of the Unions is rooted in the specific wording of Section 21, which empowers the Central Board of Health to create regulations to manage the treatment and spread of specific diseases, namely, yellow fever, small-pox, alastrim, cholera, plague and typhus.

According to the application the President is only empowered to make such regulations that the Central Board of Health is itself empowered to make. “The Coronavirus-2019 is not listed as a disease under the referenced section and [therefore] the Direction of the President insofar as it relates to the Coronavirus-2019 is made in excess of the jurisdiction granted to the President to make subsidiary legislation,” the application explains.

The application specifies that in the absence of action by the National Assembly, which could add COVID-19 to the list of diseases in the section, the Central Board of Health is not empowered under section 21 (1) to make regulations in relation to its management.

These issues which are being brought to the fore, again amplifies the importance of the work which needs to be done by the LRC, especially considering that the Public Health Ordinance is close to a hundred years old.

Against this background, it may well mean that COVID-19 which was not contemplated back in 1934 for addition in the Ordinance might now have to be included, depending on recommendations the Commission is likely to make in this regard.

While COVID measures since March 2020 were under the direction of the president, for December, the power to enact the regulations was interestingly turned over to the country’s Central Board of Health on December 1st.

Ramkarran shared that between 1999 and 2003 there was a constitutional reform process which was wide ranging and encompassed possibly hundreds of amendments to the text of the 1980 Constitution including some of the fundamental rights provisions.

The then-Constitution Reform Commission he said, which was responsible for these amendments only had six months, and the recommendations were necessarily circumscribed by the length of time it was given to do its work.

The process itself he said, arose to provide a solution to political problems facing the country and was not an ongoing process.

Since the process was limited in this way and was not ongoing in the way that a Law Reform Commission operates, however, Ramkarran explained that it was not possible for a full review of all the laws that could possibly be affected by constitutional changes.

He further explained that pre-2018 rulings by the CCJ that the savings law clause in the Constitution which saved all pre-existing laws from unconstitutionality and challenging such laws before those rulings, would have been much more difficult than they are now if they affect fundamental rights.

Housty has noted that cognizance ought to be taken for saved laws to reflect the realities of a modern developing society.

Guyana’s first ever Law Reform Commission was established in August of this year. It is an advisory body to the State and can recommend to Government amendments to existing laws, new legislation, and the repeal of existing legislation.

Retired Justice of Appeal B S Roy who was appointed Chairman; had previously told this newspaper that the commission is “fully cognizant” of its responsibilities… [and is] up to the task and ready to go.”