A recent study conducted by the UK charity, Christian Aid, assessed the cost of the damage caused by ten of last year’s most devastating weather events at around US$170 billion. These include: Hurricane Ida in the United States that killed at least 95 people; severe floods in Europe, China and South Sudan, resulting in the deaths of more than 540 people and displacement of almost a million people; and extreme drought in East Africa and Northwestern Afghanistan, forcing people to leave their homes in order to survive.

All these disaster-related events are linked to climate change and global warming that are caused mainly from the burning of fossil fuels. At the global level, when the cost of cleanup, repairs, rehabilitation and reconstruction is counted, in the long-run it could very well outweigh the revenue accruing to oil producing nations from the processing and sale from fossil fuels, not to mention the environmental damage caused, loss of life, displacement of people, and their consequential social and economic effects.

In Guyana, it is like “drill baby, drill” and forget about the future. Then, we squabble over the pittance we are receiving as oil revenue, as evidenced by the unfortunate occurrence that took place in last Wednesday’s sitting of the National Assembly. That pittance is US$534 million at the moment, equivalent to G$106.8 billion, and representing a mere 28 percent of this year’s National Budget. With the passing of the Natural Resource Fund Act 2021, which allows up to 100 percent withdrawal from the Fund in the first year, should there be some unforeseen event or circumstance immediately thereafter that causes oil prices to plunge, little or nothing will be left for future generations!

Three weeks ago, the Auditor General’s report on the 2020 public accounts was laid in the National Assembly although it was presented to the Speaker over three months ago. Since then, the print media have been reporting on various aspects of the report, mainly relating to overpayments to contractors, substandard work performed and breaches in the Procurement Act. These findings are not new and kept repeating year after year with little or no evidence of sanctions being taken against the defaulting officials. A key contributory factor for this sad state of affairs is the lack of effective functioning of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC). This important parliamentary oversight body is six years in arrears in its reporting on the public accounts, its last report having been issued some four and one-half years ago in respect of the fiscal years 2012-2014.

The PAC must recognise that no useful purpose will be served if it continues to scrutinise the backlogged public accounts sequentially, considering that in the past it took on average over four years to report on one year’s accounts, which means that the Committee will always be six years in arrears in terms of its work, unless a new approach is taken to address the scrutiny of the backlogged accounts. In a previous article, we had suggested that the Committee examines the most recent audited public accounts, in this case the 2020 accounts, with a sub-committee addressing the backlogged years. In this way, the deficiencies and irregularities identified by the Auditor General in his most recent report can be addressed expeditiously. The Treasury Memorandum, setting out what actions the Government has taken or intends to take in relation to the findings and recommendations of the PAC, will then become more relevant and meaningful.

In today’s article, we discuss two important items contained in the report, namely, the overdraft on the Consolidated Fund and Guyana’s public debt.

Overdraft on the Consolidated Fund

As of 31 December 2020, the Consolidated Fund held at the Bank of Guyana was overdrawn by $207.078 billion, compared with $124.288 billion at the end of 2019, an increase of $82.790 billion. By Section 60 of the FMA Act, the Minister is authorized to approve of the use of advances in the form of an overdraft on an official bank account to meet cash shortfalls during the execution of the annual budget. However, the overdraft must be repaid in full on or before the end of the fiscal year during which the overdraft was incurred. (Emphasis added.) Over the years, however, this requirement was overlooked, resulting in a buildup of the overdraft.

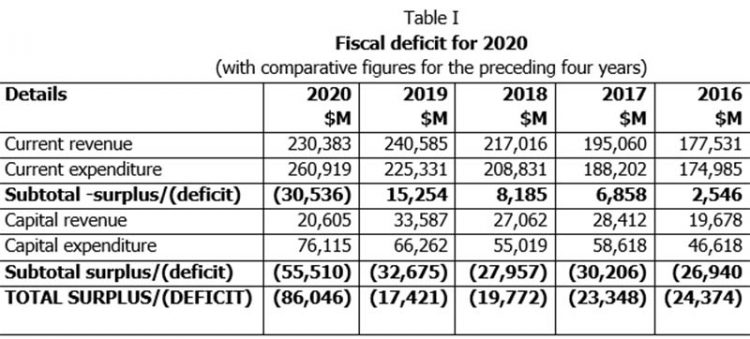

The increase in overdraft is attributable mainly to the fiscal deficit of $86.035 billion recorded in 2020, as shown at Table I:

It was the first time since 2014 that an operating deficit, i.e., current revenue minus current expenditure, was recorded, due mainly to a four percent drop in revenue collections, coupled with a 16 percent increase in public expenditure.

The 2020 budget was not approved until September 2020 because of the 2020 elections impasse. In accordance with Article 220(1) of the Constitution, pending the approval of the National Budget, the Minister of Finance can authorize withdrawals from the Consolidated Fund to meet the expenditure on essential services up to four months from the beginning of the fiscal year or the coming into operation of the Budget, whichever is earlier. This restricted access to the Fund is further elaborated on by Section 36 of the Fiscal Management and Accountability (FMA) Act. For current expenditure, withdrawals are restricted to one-twelfth of the previous year’s expenditure for each of the months in question. For capital expenditure, no new projects are to be initiated, and payments are only to be made to meet obligations for multi-year contracts. There is no constitutional or legislative provision for access to the Fund beyond this period, i.e., from May to August 2020. Unfortunately, the Auditor General’s report did not address whether there was compliance with the above constitutional and legislative requirements; how much of the total expenditure of expenditure of $313.034 billion was incurred prior to the approval of the Budget; and how much is considered legal in the context of these requirements.

There is provision for the Minister to access the Contingencies Fund to meet urgent and unforeseen expenditure for which there is no or insufficient provision and which cannot be postponed without jeopardizing the public interest. This is provided for by Article 221 of the Constitution and elaborated on by Section 41 of the FMA Act. During the period May-August 2020, four payments totalling $785.808 million were made from this Fund. The Contingencies Fund could not therefore have been used to meet the expenditure incurred during this period. In all probability, withdrawals had to be made from the Consolidated Fund for which, as indicated above, there is no constitutional and/or legislative support.

As regards the overdraft on the Consolidated Fund, we had estimated the overdraft at the end of 2020 to be $288.906 billion. Our estimate has turned out to be accurate if account is taken of the $75.678 billion that was transferred in 2018 and 2019 from the Monetary Sterilisation Account. Had it not been for this transfer, the actual overdraft on the Consolidated Fund at the end of 2020 would have been $282.756 billion.

In 1993, the Monetary Sterilization Account was set up to remove excess liquidity from the financial system through the issue of 182- and 365-day Treasury Bills. The related liability should be exactly offset by the monetary sterilization bank account, thereby creating a fully funded liability. The bank account, however, reflected a balance of $1.657 billion at the end of 2020 although outstanding Treasury Bills totalled $79.175 billion. According to the Notes to the Accounts, the difference was due to unpaid discounts due to the Bank of Guyana.

As of 31 December 2017, the Sterilisation Account reflected a balance of G$77.537 billion. At the end of 2018, the balance was reduced to $21.558 billion with a further reduction to $1.880 billion in 2019. This significant reduction was mainly due to the proceeds from the issue of the issuing of the 182- and 365-day Treasury Bills being deposited into the Consolidated Fund, instead of the Monetary Sterilisation Account. The Auditor General raised this as a matter concern. The Ministry of Finance explained that the Minister is empowered under the FMA Act to seek funding by way of borrowing in order to reduce the overdraft on the Consolidated Fund; and that the issue was more related to bridging a fiscal gap and had no relationship to monetary policy which falls under the remit of the Bank of Guyana. This explanation was, however, contrary to the purpose of setting up of the Sterilisation Account. The Ministry had also cited Section 61 that stipulates that proceeds of any such borrowing by the Government shall be paid into the Consolidated Fund. Section 60, however, requires any such overdraft to be repaid before the end of the fiscal year, as highlighted above.

The public debt

The public debt of Guyana and the servicing of that debt are a direct charge on the Consolidated Fund, meaning, they are not voted for in the Assembly. However, there are restrictions on the amount of debt that can be incurred. The amount of foreign debts cannot exceed G$400 billion. In February 2021, this ceiling was increased to G$650 billion, and the related loan agreements must be laid before the Assembly as soon as practicable after their execution. The domestic debt ceiling was also increased from G$150 billion from G$500 billion.

At the end of 2020, the public debt stood at G$415.153 billion, compared with G$388.454 billion at the end of 2019, a net increase of G$26.699 billion. This increase was mainly due to increases in both the external debt and the internal debt, the latter accounting for G$23.331 billion. In equivalent United States dollars, the external debt was US$1.303 billion, compared with US$1.287 billion at the end of 2019, an increase of US$16 million. The increase was mainly due to disbursements made on loans contracted prior to 2020 as well as the reclassification of the opening balance on two other loans. The Auditor General’s report did not explain the reason for the reclassification.

In June 2020, a loan agreement in the sum of US$14.630 million was entered into with the Islamic Development Bank for the construction of a hydroelectric project. However, no disbursement was made in 2020. In view of the dissolution of Parliament and the holding of elections, no agreements should have been entered into that has the effect of binding the State.

The internal debt comprises debentures and Treasury Bills. The former are a long-term source of financing while the latter relates to short-term financing. The following gives a breakdown of the G$23.321 billion net increase:

Description G$M

Debentures issued 2,064

Treasury Bills issued 9,227

Reclassification of NICIL Bond 12,320

Sub-total 23,611

Less: Repayment of debenture & interest charges (280)

Net increase 23,221

As regards the reclassification of NICIL bond, the Minister had signed a government guarantee in May 2018 for a G$30 billion in bonds issued by the Hand-in-Hand Trust Corporation to the National Industrial and Commercial Investments Limited (NICIL). The bond was to assist in the restructuring of the Guyana Sugar Corporation, and amounts totalling G$12.320 billion were drawn down. With effect from November 2020, this amount was transferred to the public debt, presumably because of the inability of NICIL to service the debt.