“Riots are the language of the unheard”

– Martin Luther King

“The people are not rioting. It’s the Government who are rioting and shooting down the people”

– Quote used in Walter Rodney’s History of the Guyanese Working People 1881-1905

Guyana’s history is inundated with rebellions and riots of different levels of intensity, effect and impact. This article attempts to provide, in brief outline, the most prominent of these protest acts, whether major riots or ‘disturbances.’

The forms of protest during the period from Emancipation to Independence included strikes, petitions, inter-ethnic violence, vocal protests, riots, marches, sit-ins, “rowdyism”, sabotage (including fires), pilfering, absenteeism, contentious gatherings, desertion, and foot dragging. This was not all. There were hundreds of individual and minor collective acts of resistance and defiance and public disorder in the period.

Handbills, Governor’s dispatches, oral memory, and the most prevalent source of all, newspaper reports, were all rich sources of information on the origins, form and outcome of these social explosions. The period under review covers from emancipation (1838) to independence (1966). The antislavery rebellions in Guyana in 1731, 1762, 1763, 1795, 1814, and 1823, among other uprisings, are thus outside the remit of this piece.

Newspaper reports, written from the perspective of the “rational” and powerful people in the colony, usually referred to rebellion/or riots in very pejorative terms. Thus, newspaper editorials or on scene reports invariably described plantation or urban unrest, not as stemming from the human considerations of those protesting, but often deemed protesters as “hooligans” “mobs” or “discontented” thereby diminishing or dismissing, through public narratives, the agency of the aggrieved constituency. The British “Riot Act’ was first made into law in 1715. Universally applied subsequently to its many colonies, it allowed, inter alia, for any “local authorities to declare any group of 12 or more people to be unlawfully assembled and to disperse or face punitive action.”

Causes of Unrest

The long record of instances of unrest in Guyana must be seen in the wider context of colonialism, imperial policy, planter domination, socio-economic conditions and ethnic differences in urban centres and villages and towns in the period. The typical causes of unrest in Guyana included unemployment, unpaid wages, responses to scabs, unfair wages, racism, pass laws, breach of (labour) contract, brutality or mistreatment by overseers and managers or police, and sometimes the inability to use or access (as in the case of indentured Indians) the Immigration Agent General. Some of these uprisings/riots were racialized and characterised by inter–ethnic violence.

Many of the protests and riots discussed in this article did not initially spur social and political movements (except perhaps labour movements) but must have had a cumulative effect on the advent of later movements and organisations.

A deep scrutiny of every event would require the inclusion of cause(s); profiles of activists and/or leaders; a catalogue of grievances; and an outline of the collective action in each case. Such deep enquiry is not possible here.

A few of the riots/disturbances listed in the article have had the benefit of some research and exposure. The 1856 and 1889 riots, for example, and especially the 1905 and 1913 riots, at Georgetown and Rose Hall, respectively (and to some extent the 1924 Ruimveldt riots), have received some degree of published analysis. Not so with 1896, 1869, or the disturbances caused by Rev CN Smith.

Most of the rebellions/riots mentioned were followed by an official enquiry which, in almost all cases, sanctioned the use of official force. Colonel De Rinzy, Inspector-General of the Guyana Police Force, was a well-known repressor-in-chief of a few of the rebellions, and his repressive presence was especially felt at the Non Pariel (1896), Georgetown (1905) and Rose Hall (1913) riots. De Rinzy, who had arrived in the colony in 1891, even gave a public lecture on how to suppress riots. He died in 1916 and was buried in Georgetown’s St Sidwell churchyard after a huge funeral. Another policemen, Lushington, also gained notoriety for repression in the 1905 riots.

The 1896 Non Pariel riot for its part was very consequential for the British colonial project, coming in the wake of other Anglo Caribbean protests in places like Trinidad & Tobago, Grenada, St Kitts, St. Vincent and Dominica. The arrival of Maxim machine gun in the colony in 1896 was significant. This famous and efficient killing appliance was notorious for its widespread usage in the suppression and murder of civilians and anti-colonial fighters in almost every European colony around the world.

One historian described the resistance as emerging from a “depression strangled sugar proletariat.” At the base of all this instability was the sugar economy and its volatile local and global viability. In the 1880s, for example, European (mainly German) beet sugar began to challenge the planter monopoly and this led to dissension on the estates as planters tried to recover losses by anti-working class measures. It resulted in the creation of the influential 1897 Royal Commission.

The 1905 riots are perhaps the best chronicled of the Guyanese rebellions. For detailed assessments of the origins, course and outcome(s) of 1905 see the respective works of Walter Rodney and Kimani Nehusi, among others.

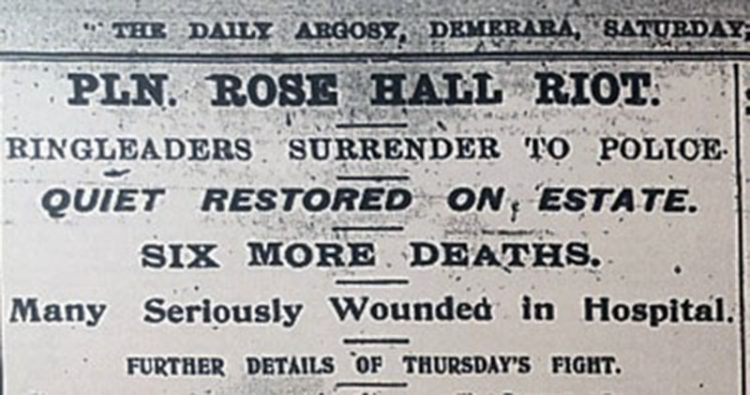

The 1913 riots at Rose Hall was one of the most violent in the colony’s history. During this riot, caused by the issue of workers leave and transfer of protesting labourers, a police corporal was killed along with 15 indentured labourers. The labourers killed were Bhoolay, Badri, Hulas, Motey Khan, Sohan, Juggai, Surjoo, Gafur, Sadulah, Roopan, Nibur, Jugai, Durga, Lalji, and Gobindi, the lone female among the fatalities.

The description in the press of the fatal wounds, as described by the Government Medical Officer, were graphic. Motey Khan, for example, was reportedly shot four times “on the lower side of the left blade bone above the right collar bone and under the left ear, all the result of rifle bullets…”.

For an incisive summary of the 1913 riots see Gaiutra Bahadur’s article in Stabroek News, March 13, 2013.

The 1924 Ruimveldt Riot

In the 1924 Ruimveldt rebellion, three to four thousand people had gathered to protest over wages and conditions of work. The British Guiana Labour Union was trying to expand its labour base into the East Bank and the British Guiana East Indian Association was also mobilising against conditions on sugar estates on the East Bank area. The combination of these two events provided the conditions for the mass labour rebellion which resembled a multi-racial constituency of the aggrieved. About 600 hundred protestors had actually “menaced” the La Penitence bridge before the police opened fire. Thirteen were killed and twenty-four wounded. After the shootings, Ann Spackman (1973) reports there were “four attempts at arson, all against whites, and on two homes which were attacked were pinned the following notice: ‘To All Europeans! Why We Have Done It, Because You Have Shot Our Fellow Men East Indians, And Negroes, And Throughout Demerara, We Are Not Satisfied With Shooting, And Are Seeking Revenge’”

The turbulent thirties

The 1930s, like elsewhere in the region saw worker protests, strikes and estate rebellions like at Leonora in 1939 and also the lesser known ‘Church Army’ discord.

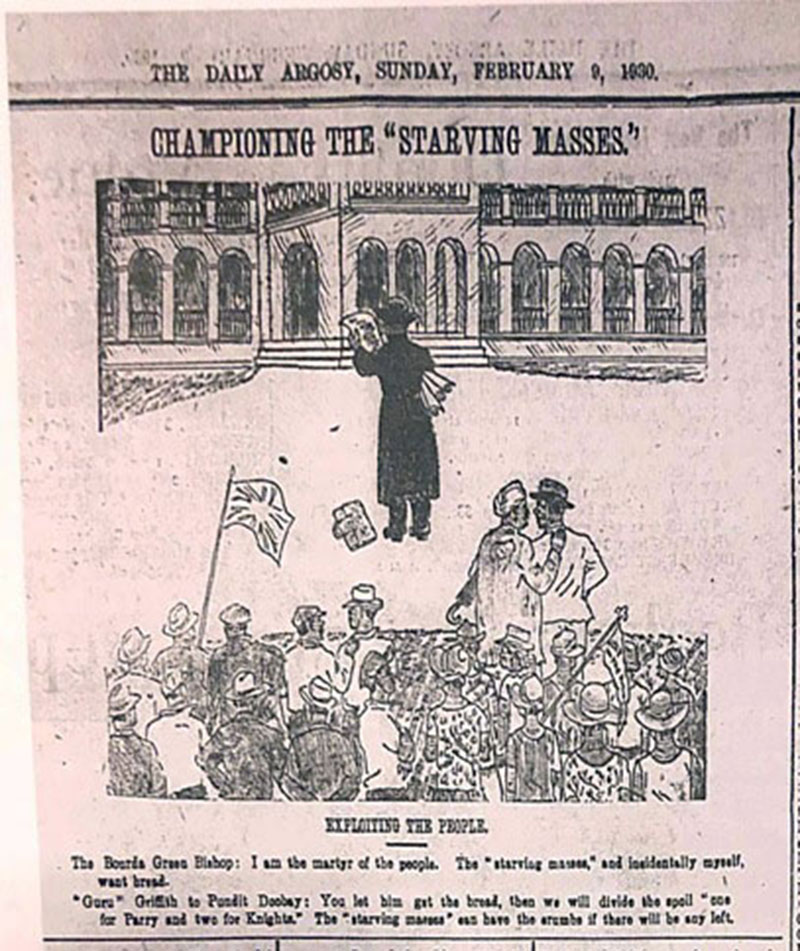

The leader of the ‘Church Army,’ CN Smith, also known as the ‘Bourda Green Bishop’ was another activist in the vein of Angel Gabriel of 1856 fame. Given the significance of his actions in the 1920s and 1930s, it appears strange that he is not well known as one of the pre-independence agitators and ‘disturber of the peace’. The Rev Smith carried, for a few years, a campaign on behalf of the working people that appeared to be thoroughly confusing to the colonial authorities. For one thing, the factors of “madness’ and religious fervor were cited as factors that made him a threat. For a while, Georgetown was fascinated with the activities of Rev Smith and his followers. While his congregation of men and women idolized him, one can gather from the newspaper reports that this adulation was not only centred on his religious zeal and authority over his followers (which included a strong component of market women) but fed by his activism against unemployment on behalf of the city poor.

In 1935, there was another, little-reported protest generated by the Italian fascist invasion of Ethiopia. About five hundred Guyanese, including black veterans from the First World War, gathered to protest the Italian invasion and to call for their right to enlist to fight on behalf of the Ethiopians.

One account set the scene:

“In early October, 1935 various organizations met in Georgetown Guyana and petitioned King George V to be allowed to fight on behalf of Ethiopia. ‘Twenty years ago Negroes fought to save white civilization’, declared the president of one organization, ‘surely they cannot now be refused permission to fight for what they regard as the symbol of their own civilisation.’ So much concern over the Ethiopian tragedy was manifested in Guyana that the censors banned a Paul Robeson film, ‘Emperor Jones’ fearing that it would precipitate racial strife. When a rumour was spread that Italian spies distributed poisoned candy to Georgetown school children it actually led to a panic. Several schools were closed. Frantic mothers kept their youngsters indoors and a white school inspector was almost killed by an enraged mob which took him for an Italian.”

Of course, throughout the region in the 1930s any protest, such as the rally for Ethiopia, would have interlocking causation, including the economic depression extant in the region and the world in that decade.

The “1960s”

On the cusp of independence came the racial riots or inter-ethnic conflict, customarily identified as “the 1960s”. The period tends to be identified as one collective event over the three years when there were in fact three separate riots (1962, 1963, and 1964) arising out of different political and labour issues albeit under the consistency of politcal and social division its concurrent partners, race and ethnic violence.

The list makes for grim reading. While the definitive history of the riots and disturbances of more than a hundred years duration is yet to be written, it demonstrates that there was almost no period (or year) in the country’s history as a colony that the plantation/colonial system went unchallenged by the people of Guyana.

A Listing of Riots and Disturbances from Emancipation to Independence

1846: Disturbances at Leguan

1847: 14-week general strikes, described by Walter Rodney as the longest strike in Guyanese history until the 1977 135-day strike

1848: Labour strikes (Plantation Palmyra fires)

1856: Angel Gabriel riots (1 constable died; looting, damage to buildings, shops burnt)

1862: Anti-taxation and dispossession disturbance at Friendship

1869: Leonora riot and strike

1872: Meten-Meer-Zorg disturbances (inter-ethnic violence)

1872: Devonshire Castle riots (5 killed, 7 wounded)

1873: Skeldon, Uitvlugt, Eliza & Mary – inspired by price paid for shovel ploughing, 25 rioters arrested

1879: Skeldon riots – fighting between “East Indians and creoles”; 16 admitted to hospital; 30 arrested

1888: Enmore and Versailles disturbances

1889: Cent Bread riots (violence, burnings)

1894: Disturbances at La Bonne Mere, Success, Leguan and Farm

1896: Non Pariel Riot, (5 killed)

1899: Golden Fleece, Mon Repos, Blairmont, and De Kinderen

1903: Strike at Friends (8 killed, 5 wounded)

1905: 8 killed; 15 wounded; 105 convicted for rioting.

1912: Friends (1 killed)

1912: Lusignan (1 killed)

1913: Rose Hall (16 killed)

1924: Ruimveldt (13 killed, 24 wounded, 147 charged)

1920s 1930s: Church Army protests – Georgetown (Rev CN Smith, leader of the rebellion detained and jailed in 1933)

1935: Outbreak of strikes; violence and destruction of property on the East Bank and East coast; Veterans assembled to press support for Ethiopia and to volunteer to fight the Italians

1936: strikes on estates, minor disorders

1938: labour unrest in Berbice and East Coast Demerara, (163 charged)

1939: Leonora riot (5 killed)

1947: Strike at Mackenzie of 1,300 workers, some unrest & sabotage

1948: Enmore – eponymously referred to as the ‘Enmore martyrs’ (5 killed, 9 injured)

1957: Skeldon disturbances (13 workers wounded)

1962: Kaldor budget; anti- government – trade unions, church, UF, PNC (ethnic riots: 6 killed, 80 wounded)

1963: Labour Relations Bill; general strike (ethnic riots 13 killed, 730 injured)

1964: GAWU strike (ethnic riots, 176 killed, 920 injured)

Nigel Westmaas is an Associate Professor of Africana Studies at Hamilton College in the United States.