Today’s column will simulate two scenarios of expected money inflows into and outflows from the Natural Resource Fund. All simulations are based on the NRF Act of 2021. The Act allows for higher early withdrawals from the Fund. Several justifications for high initial withdrawals were outlined by government officials. First, the dire shortage of the present infrastructure has to be addressed. Second, the existing infrastructure – especially those pertaining to drainage – will require significant upgrade; and in some cases, they will have to be reconstructed. Third, building infrastructure is akin to transferring wealth from the present to future generations.

As noted in a previous column, I am sympathetic to these arguments. As was done in the 2022 Budget, future Budgets are expected to outline amounts for several big-ticket projects. The problem I have relates to the limited transparency surrounding the procurement process. The cheapest bidder is not always the best contractor, especially when insider information was provided. I am still puzzled as to why the government needs a BOOT for the proposed permanent-structure Demerara bridge given that it knew how much monies will enter the NRF over the next decade.

The simulations I propose below will indicate that there is enough foreign exchange to build the bridge. It is perhaps better to have credible bidders from The Netherlands as well as other places and have the government fund it outright. The BOOT arrangement creates a de facto external debt. When completed under a BOOT structure, the new bridge will be an asset to Guyana, but it will have an accompanying liability as an external debt has to be repaid with interest. However, funding it from the NRF provides an immediate addition to Guyana’s net worth. Furthermore, I am certain the interest forgone on the NRF is much smaller than the interest rate the BOOT arrangement will extract. Moreover, given the poor urban planning in the past 30 years, the bridge will attract significant extra financial cost and environmental stress to those living nearby once it is placed in the envisioned location. I still believe a better location is south of Grove/Craig Village. This is my minority viewpoint, however.

The same principle applies to the pipeline aspect of the gas-to-energy project. Exxon is essentially providing a foreign exchange debt to Guyana that will be repaid with cost oil, according to the limited information we have. The Guyanese people are yet to be provided with a document indicating the financial terms of the pipeline, let alone the other aspects such as the gas processing plant and the power plant.

The external-debt principle applies to the Amaila project as well. The BOOT creates an external debt that will be repaid by a power purchase agreement, most likely complicating the Vice President’s anticipated purchase price of 0.079 cents per Kwh. Upon completion, Amaila adds both an asset and a liability to the country, but not a net worth for at least two decades. The government may want to consider the external debt aspects of each big-ticket project. Of course, some debt will have to be incurred, but comparing the interest cost of a future project and the forgone interest the NRF makes may be a good rule of thumb.

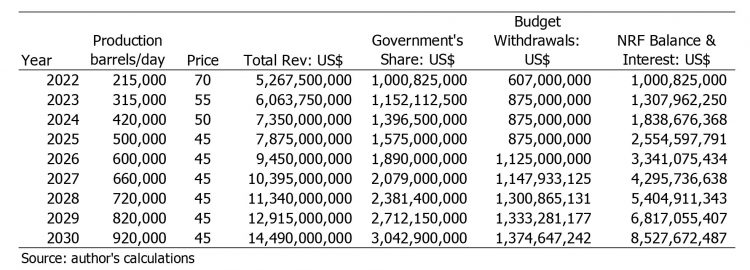

The first table provides a ‘best-case’ scenario relating to price and production. Information floating around in the public domain indicates that Guyana does not reach the 1 million barrel per day mark until around 2030. Yet, others suggest that the one-million target could be reached by 2027. In my assumptions, I settle on the daily production given in the tables. It is unlikely that any plant will run continually at maximum capacity.

The prices are also year averages that smooth out the random fluctuations. The first table shows a more favourable price outcome. However, it is not unexpected for price to spike to $100 a barrel (or higher) for a short period of time. It is also likely that the price can average around $40 a barrel for a much longer time than it would at $100.

Readers would recall that I always assume that there will be full cost recovery for a long time given the lack of ring fencing. However, I was reminded recently that the government is receiving oil windfall, on average, 19% of total revenue. That exceeds the 14.5% of total revenue under full cost recovery. Therefore, for my simulations, I initially assume that the government gets 19% and increase it to 21% as cost is recovered. Nevertheless, we will always be guessing what is the real profit oil since no one in the early days tried to pin down a unit cost.

The final assumption pertains to an interest rate for investing the monies in the Fund. I assume that interest amounts to 3% and they are compounded annually. Some will say that this is quite conservative. That may be so, but remember that many of the financial products will require a fee. Therefore, imagine the 3% as the return after the fees are paid. And, remember, the NRF Act of 2021 – as did the previous one – opens the door for many consultants for demystifying treasury bills and mutual funds.

The Act proposes several annual tiers of early withdrawals. The percent tiers are linked to the first US$500 million (100%), second US$500 million (75%), third US$500 million (50%), fourth US$500 million (25%) and fifth US$500 million (5%) received in a single year. Note that the percent in each parenthesis shows the amount to be withdrawn per tier of US$500 million received in a given year. There is a sixth tier of annual withdrawal amounting to 3% of the accumulated balance in the NRF that exceeds US$2.5 billion.

Following these percent thresholds and assumptions, the first table shows the amount the government could withdraw for each budget until 2030 as well as the accumulated savings that will likely result. The fifth column showing the government’s share of the total oil revenue is important. Depending on the size of the annual windfall, the government determines its annual withdrawal for budget spending subjected to the percent tiers. It should be noted that each year’s budget withdrawal is a function of the amount of oil windfall the government gets in the previous year, which itself is dependent on the total revenue of oil production. So, the 2023 budget is based on oil windfall in 2022 and so on. Moreover, the government could possibly take out US$875 million for the 2023 Budget after the well-known withdrawal of US$607.4 million for the 2022 Budget (see 6th column). The annual withdrawal increases in a nonlinear manner to reach almost US$1.5 billion in 2030.

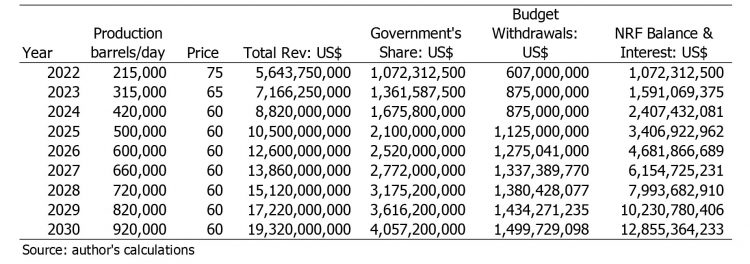

I also ran the numbers with lower assumed prices, while keeping everything else the same. These are outlined in the next table where I assume a more sustained average price of around US$45 per barrel for a much longer period. The annual budgetary withdrawals are reduced, but not substantially given the way the law is written. The main effect is on the accumulated savings, which would be reduced by over US$4 billion by 2030. The conclusion we make is a low long-term price will greatly reduce savings, but still allow government to spend big.

The government may voluntarily decide to reduce its spending, but that will be dependent on a more consensual political environment. Tit-for-tat conflict at the level of political leadership and the pro-ethnic strategic vote will most likely complicate fiscal policy and development planning. Having said that, it is a good time to start structuring some of large spending as automatic stabilisers such as unemployment insurance in the event of steep downturns. Flexible cash grants – akin to an earned income tax credit – via the tax code would also be a welcome addition for addressing the certain inequality these spending will engender.

Comments can be sent to: tkhemraj@ncf.edu