In February, 1916, former US President Col. Theodore Roosevelt paid an unofficial visit to British Guiana (Guyana). He came to the colony through the instrumentation and invitation of the Royal Agricultural and Commercial Society (RACS).

Roosevelt’s one-week visit is established in the public record as one of three visits by a US President (previous or former) to Guyana. President James Carter is well known in modern times for the role he played with the Carter Center in several visits linked to consequential national elections. The other visitation was from General Dwight Eisenhower before he served as US President, 1953-1961. In 1946, Eisenhower had visited the Atkinson base (now the area covered by Guyana’s international airport) in a short, unofficial stopover in the country.

Arrival

Col. Roosevelt had arrived from New York on a steamship associated with the Quebec line, fittingly titled SS Guiana. The SS Guiana, deemed the “workhorse” of the Caribbean fleet, was a combination of luxury liner and trading vessel with a large hold for hogsheads of molasses, sugar, and rum. Greeted with hand-clapping and waving of handkerchiefs at the Georgetown docks with his spouse Edith Roosevelt and delegation in tow, the 26th president of the US reportedly “raised his panama hat to the gathering.” The large reception committee on the docks included Sir Walter Egerton, Guyana’s colonial governor, and William Beebe, famed naturalist and explorer also known for his celebrated deep-sea submersible, the bathysphere. In Water Street, hundreds lined up to get a glimpse of Roosevelt. Comparatively, even given respective population size, an estimated 250,000 people had greeted Roosevelt on his visit to Buenos Aires in 1913.

Roosevelt’s 1916 stopover was part of a larger tour of South America and the Caribbean, which included brief stops in Martinique, Barbados, Dominica, St Kitts, Guadeloupe, St Lucia and St Thomas.

The Guyana leg of his Caribbean sojourn was unquestionably associated with Roosevelt’s conservation interests and efforts. ARF Webber (Centenary History of Guyana )in a pithy mention of the event indicated that the visit “had no political significance”. Before his arrival, the Daily Argosy observed: “visitors of worldwide distinction to British Guiana are so few and far between that we are proportionately gratified when the opportunity occurs”. Making assumptions based on his reputation and history of shooting at wildlife the newspaper mused that Roosevelt would “have an opportunity to shoot real crocodiles in the Essequibo and Demerara rivers…”

Prior to landing on Guyana’s soil the Governor had invited Roosevelt to stay at Government House but the former President declined and opted for the Park hotel, emphasising the informal nature of his trip. He subsequently visited the governor at his home after which Roosevelt and his party undertook a sight-seeing tour of the sea wall, the Botanic gardens, and the golf club on the East coast.

Roosevelt the President

The Argosy editorial observed that Roosevelt’s “enthusiasm and prejudices alike may sometimes have led him beyond the bounds of discretion but he stands today pre-eminently the most distinguished and the strongest personality in the United States.” The description “beyond the bounds of discretion” was an Argosy understatement given the mixed review of Roosevelt’s two terms in office. After all, Roosevelt (labeled by one scholar as “perhaps the intellectually best prepared individual who ever served as President of the US”) was considered an enthusiastic imperialist, and his performance in the field of militarism and conquest was prosecuted with even more gusto than his presidential predecessor William McKinley. During his time Roosevelt was involved in attacks on the Philippines, Cuba, the establishment of sovereign like rights over the Panama Canal zone, ensuring the propping up of so-called ‘banana’ republics in Central America, shooting wild game in Africa, and a number of other showy actions as part of the American expansionist project, as defined by the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 along with the “Roosevelt corollary” which stipulated that the US could unilaterally intervene in Latin American countries.

Described variously as rancher, historian, president, and explorer, Roosevelt was the first US president to settle a labor dispute and was likewise credited with some measure of anti-trust legislation in general and certainly challenged the rising financier JP Morgan at the federal level during his presidency. For example, Roosevelt held the view that the “central government should be superior to any private economic power” as he broke up the private railroad empire using the 19th century Sherman antitrust Act.

Like other US presidents in the Jim Crow era, Roosevelt held openly racist views about African Americans. Roose-velt once decried African Americans “…as a race and in the mass … inferior to whites.” At another time, he denigrated the fitness of black soldiers and by all accounts appointed fewer blacks to federal positions than his predecessor William McKinley. Four years before he arrived in Guyana, he had excluded black delegates from his new Progressive Party convention. But even Roosevelt’s superficial overtures to black America created controversy and pushback. When he invited the very conservative and reformist black American Booker T Washington to the White House in 1901, it provoked a firestorm. The outcry over this “breaking of bread between the races on equal terms” pushed Roosevelt to an even more defensive posture on the race question and a retreat from any mild reforms to the Jim Crow system. In essence, he desired a nation “dominated by the descendants of Anglo Saxon settlers.” His successor as president, Woodrow Wilson, would take institutional racism to new heights.

Now, this self-styled imperialist and adventurer dropped in on Guyana with more demure and even visionary post-presidency interests. In his new mode and public persona Roosevelt self-proclaimed his visit to Guyana as a conservationist drive in assisting efforts to protect the environment. Roosevelt’s conservationist interests were strategic and pre-dated his Guyana visit. Described as “America’s conservationist in chief,” he had cautioned about the exploitation of the world’s natural resources during his presidency and was behind the North American Conservation Conference of 1909, one of the earliest international conferences addressing the depletion of the world’s natural resources. In like vein, Roosevelt was eerily prescient in “predicting that it would be necessary to invent or develop new sources of the use of energy and fossil fuels” amid his concerns about “non-renewable world resources.’”

RACS Speech

When he spoke at a function hosted by the RACS, founded in 1844, Roosevelt mentioned that he had always been interested in the Guyanese territory and history and claimed he had read James Rodway’s history of the colony (Roosevelt reputedly read 20,000 books in his lifetime). “Everything”, Roosevelt stated in an Argosy report, “must be done for the development of your (Guyana) coastal belt, and there is an enormous lot to be done in such development….I wish to see the timber and cattle trade develop in corresponding fashion.” Turning to Guyana’s staple product he said, “I appreciate the full importance sugar will always have in this colony. Sugar is going to increase in importance, but I want to see the development of other crops, not only rice, but rubber and limes…I want to see a development of all these industries so that your eggs will not be all be in one basket.”

On his trips Roosevelt usually delivered lectures on American internationalism, the Monroe doctrine and Democratic ideas and some of these seeped into his RACS speech but he avoided US foreign policy.

Waxing lyrical, he assumed his proclivity for banter with his listeners: “I am speaking as a democrat, as a reformer and as a man of liberal tendencies, and I am convinced that just as you can’t afford to do without education you can’t afford to do without religion.” Roosevelt joked that he was not a “professional peacemaker” but had always wanted peace and was “always willing to fight for it,” which drew laughter from the audience. It was the only hint of a reference by him of the World War raging mainly in Europe at the time.

The Daily Argosy enthused over Roosevelt’s “characteristically brilliant” speech, which the paper claimed was “witty, forceful, sincere and sustained by an encouraging or flattering belief in the future prosperity of Demerara.” That prosperity included Roosevelt’s reflexive imperial instincts included in his comment that he hoped “to see both capital and labour brought into the colony, and the introduction of one will tend to encourage the other.”

Mazaruni Sojourn

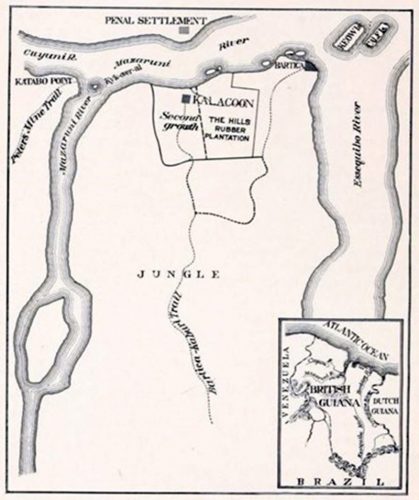

After the niceties of Georgetown speeches and meetings, Roosevelt took off with his spouse Edith for a weekend visit to Mazaruni in northern Guyana on the pre-arranged invitation of William Beebe at the latter’s outpost at Kalacoon House (loaned to Beebe by a Guyanese rubber plantation magnate). Beebe had established a New York Zoological station at Kalacoon. While in the Mazaruni, Roosevelt observed the flora and fauna and praised the work of Beebe’s naturalist mission. The former President also visited the Penal settlement where he was loud in his acclaim for the “scrupulous cleanliness and order” observed in the institution. After the prison appointment, Roosevelt visited lime and rubber plantations in the area.

Back in Georgetown from the Mazaruni, Roosevelt said he “did not see a single fly or mosquito, although they slept under mosquito nets with the idea of keeping away vampire bats,” noting that a member of Beebe’s party had sat up all night with a 22 calibre gun to shoot any potential bat harassment. He lauded Beebe’s research and said it would be “of the utmost importance to the whole world of natural history, and too much significance cannot be placed upon it. You have a splendid country here awaiting development and are able to offer innumerable opportunities’ for tourists, scientists and capitalists. I am extremely glad that I was able to find time to visit British Guiana and only repent that I cannot prolong my visit. No one could have been received with a more genuine welcome then we have had.”

Roosevelt, on departing Guyana told the press, with barely hidden condescension that he had “great confidence in the future of your colony. You have measurably realised here the ideal of treating men on their conduct, and giving to each man a fair choice of avoiding the twin pitfalls of hard intolerant arrogance on the one side and foolish sentimentality on the other.”

Trinidad was the next stop after he left Guyana and it was in Trinidad that Roosevelt floated an interest in being nominated once more to run for President of the United States. It never happened and he passed away in his sleep in 1919.