One of the main features of Guyana’s historical record is its sluggish or unmotivated research and reference about the country’s mainstream historical figures and/or protest movements and individual protests. This absence of a wider narrative extends to individual working class heroes sprinkled throughout Guyana’s political history, inclusive of the little known figures who for moments at a time shook the foundations of a city, if not the colony. For example, it took a book by Clem Seecharan to popularise the writings of Bechu, the Indian immigrant and journalist in late 19th century Guyana who had excoriated the inequalities and iniquities of the society through the available newspapers. Then there is the militant worker ‘Long Walk,’ of the 1905 riots fame, who Walter Rodney highlighted in History of the Guyanese Working People 1881-1905. Another character, who, given the significance of his actions in the 1920s and 1930s, is oddly omitted from the main historical record(s) as one of the early “disturbers of the peace” against economic injustice was the Rev Claude Newton Smith, the so called “Captain-General” of the “Church Army Mission of America”.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, this African-Guyanese street preacher carried out, for a few years, a campaign on behalf of the working people that appeared to be both alarming and thoroughly confusing to the colonial authorities in British Guiana. For one thing, the factor of his “sanity” entered into the equation, at least from the standpoint of the colonial press. There was also a religious angle to the whole imbroglio, with sprinklings from the gospel. For a while, Georgetown was captivated by the activities of Rev. CN Smith. While his congregation of men and women idolized him, one can gather from the newspaper reports that this adulation was not only centred on his religious zeal and authority over his followers but fed also by his social activism on behalf of the urban poor at the time. While the official newspaper reports derided and mocked CN Smith’s antics and public displays, his ability to galvanize the public to protest social, political and economic conditions was manifest.

In a very insightful article “How do Whispers become Movements,” the author Susie Linfield (New York Review of Books 2022) identifies, in pre social media times, several areas of agency responsible for the birth and activity of social moments. Included among them are street corner meetings, union headquarters discussion, lectures, newspapers, rumours, debates, petitions, “ruminative letters”, and rancorous chatter. Several of these iterations of agency apply to Smith’s activities in Georgetown in the early 1930s, when he was the focus of attention from hostile newspapers and local colonial government figures.

During the long period of colonial rule, it was a distinct feature of individual and mass protests that they almost always relied on physical symbols of power and the colonial order as places to go to “represent” the people. The Public Buildings in Georgetown was one such venue along with Government House, Bourda Green, and the courts, which were always centres of commingling and agitation to pursue change, reform or rebellion, as we witnessed in other labour and unemployed strikes, rebellions and riots. All of these places witnessed the activity of CN Smith. Like other social and political activists of the period Smith focused mainly on the people’s situation, albeit from his own, sometimes incoherent, idiosyncratic outlook.

The economic crisis in the 1930s is well chronicled – a decade of despair caused mainly if not wholly by the ripples of the Great Depression of 1929. In this period poor sanitation and public health, unemployment, meagre education opportunities, and desire for adult suffrage were all at the centre of social and political fatigue and agitation. Shop assistants for example, were “subject to a tirade of abuses and even threats to be splattered to the ground for the simplest of mistakes…a shop assistant [trying] to quench her thirst had the glass snatched from her hand and the emptying of the pitcher of water…” The Rev. CN Smith’s advocacy in the few years he came to prominence must be seen in the light of these conditions in the colony.

The uncomplimentary reporting in the press brought CN Smith to prominence sometime around September of 1929 during an unemployment demonstration. Mocking descriptions of Smith by the press included “avowed champion of the oppressed” and “ranting leader.”

Smith takes case to Brickdam

CN Smith arrived at the Public Buildings in February 1930 accompanied by what was described as a “very large crowd”. The protestors, prior to the meeting with the “Officer Administering the Government” C.D Douglas Jones (CMG), sang “rule Britannia,” calling variously for “employment relief” and for the government to “save them from the cemetery.”

Also among the people assembled in front of the Public Buildings was John Lucie-Griffith, Pandit Garbharan Doobay and “officers of the army,” including “People’s Deputies of the church Army” John Moore and William Phillips Edward Barker (“chaplain”) Ms Ellie Van Rossum (Colonel”) and “Adjutant” Virginia Latour. For his part, Lucie–Smith, often described as a professional politician, was quite a character and his name was a staple in the Guyanese political world from the 1920s to the early 1950s, albeit with the shadow and tinge of opportunism. On the government side of the meeting were CD Douglas Jones (Office Administering the Government in the absence of the Governor), the Assistant Colonial Secretary, the acting Attorney-General, and the Inspector General of the Police. The fact that the colonial authorities in British Guiana could decide to negotiate with Smith was testimony to acknowledgement of the social and economic pain that even the state knew.

Hubert Critchlow, of the British Guiana Labour Union, who was invited to appear with Smith’s delegation, disagreed with aspects of Smith’s tactics, calling his resolution to the Government delegation as “political”, inferring by this statement that he agreed with the Officer Administering the Government that including the issue of the “extension of the life of the present Executive council” should be excised from the negotiations. Critchlow subsequently pulled out of the delegation and Smith and his group proceeded with the meeting. Smith told the colonial delegates that he was “allied to the Church Army of America and had been sent as an apostle to protest the interests of the scattered sons and daughters of the great Continent.” Smith had earlier submitted his demands including taxation and unemployment relief; and criticism of the extension of the life of the Executive council and demanded elections. He also called for infrastructural projects to aid employment inclusive of a hinterland railway, a bridge across the Demerara River and changes in the diamond industry.

For their part, the colonial government delegation told Smith they hoped for the “revival of the timber and sugar industries” and proposed “releasing bauxite concessions…which would afford employment.” They also promised to spend money voted for “repairs to public buildings etc. at once, so as to give relief to the suffering people.” At the end of the meeting Smith went back to his headquarters and addressed his supporters. He told his flock that “by virtue of his office for the past seven months in this part of the vineyard he had fed people and orphans. The lining of his coat was worn and he personally was for several days in distress to find something to eat.” Smith alleged that he became so concerned with the plight of the people he paid $8 “to the poor” out of his personal funds. Smith likewise claimed he had “fed white people in other countries and he had come back here to feed black people.”

The newspaper and/or other sources do not indicate or provide any clues as to why Smith’s church was titled “Church Army of America” but there were religious antecedents and local and overseas movements from which he might have borrowed the theology and the gospel of the poor. One such was the “Church Army” founded in England in 1882 by the Rev. Wilson Carlile, who “banded together an orderly army of soldiers, officers and a few working men and women, whom he and others trained to act as Church of England evangelists among the outcasts and criminals of the Westminster slums.”

For the remainder of the year Smith was either in court or on the “battlefield” of Bourda Green (where he and his flock camped out on one occasion). On June 26, 1930 Smith was back in the courts after a clash with police. He told the magistrate that it was a “very concocted plan by the white men to put him into prison” and that he “would die for his race…” Smith was eventually taken to the Brickdam Police Station, where he obtained bail later in the evening.

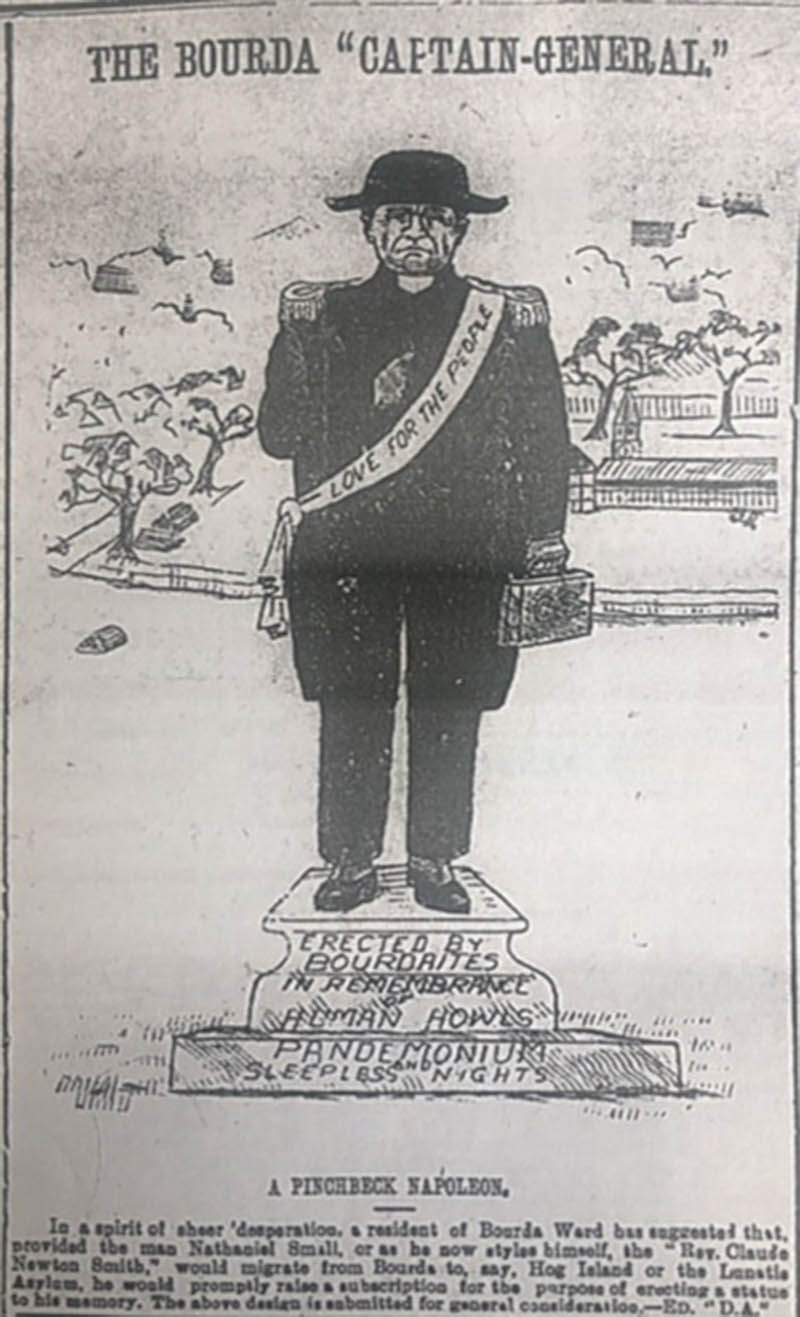

For his remonstrations of the economic state of his constituency and followers and other antics, including frequent court appearances and sometimes bizarre arguments, Smith was lampooned by the colonial newspapers – one of which deemed him a “pinchback Napoleon.”

The story of Smith resumes in available newspaper reports in 1933.

Smith’s travails in 1933

In March 1933, Smith was arrested and sent to the Georgetown Jail to serve 272 days. The Daily Chronicle reported on the arrest in the following way:

“Armed with the warrant for Smith’s apprehension, and accompanied by Major C. P. Widdup, Deputy Inspector General of Police, Capt. C. C. Murtland, District Inspector, and two policemen District Inspector Billyeald arrived at the hall of the Church Army of America around 2 p.m. and found Smith “preaching” to a large number of women squatted on the floor. After reading the warrant, Mr. Billyeald calmly took Smith away from the hall as the women “soldiers” of the Church Army of America wept bitterly.”

When he was taken to court, further drama developed with a back and forth between Smith and the Magistrate: “May it please Your Honour, I was called at the Brickdam Police Station sometime last week, and I was told to report,” Smith claimed.

The Magistrate: “that does not matter anything to me.”

Smith: “Your honour, May I point out…”

The Magistrate responded: “Oh, be quiet, Mr. Smith. The point set out is that the ticket-of-leave licence is granted by His Excellency the Governor to work prerogatively. The Ordinance expressly states that the Governor has the power to revoke the licence.”

Smith: “Under certain conditions, Your Honour. May I have the privilege of engaging Counsel?”

Magistrate: “I am afraid not. “

Smith (angrily): “Will you please give me some privilege. I am a British subject and this is a British Court, and I should have had the opportunity of engaging counsel. I do not know the reason for being here. Your Honour, will you give me some time to engage counsel?” Continuing, Smith said: “Your Honor, I want to know if the Governor has the power to take a man out of prison when he likes and throw him back when he likes. You can’t pick up a man and throw him into prison like that.”

Magistrate: “Have you the Licence here, Mr. Smith?”

Smith: “No, Your Honour… (loudly)May it please Your Honour, I was called at the Brickdam Police Station sometime last week, and I was told to report.”

Captain Murtland (police prosecutor): “He has to produce the licence, Your Worship, or stand the chance of being given an additional three months.”

Smith (loudly): “There has been a continual endeavour to put me back. They threw me in for three years for perjury, took me out, and now…What are the conditions, Your Honour?”

Magistrate: “If you think that an injustice has been done you, Mr. Smith, I shall read the Section. The Magistrate then read the section which pointed out that a ticket-of-leave convict could be sent back to jail at His Excellency’s pleasure.”

Smith (pulling a bundle of papers out of his hip pocket): “I have brought some correspondence I received from the Governor only a day ago. It does seem that something is hidden. A great injustice is being done to me in this Colony. I had to report persecutions by the Police. What are the conditions under which I am charged, your Honour.”

Magistrate (smilingly): “Truly I do not know, Mr. Smith, but I have a suspicion as to what caused it.”

After the back and forth, the police then escorted Smith out of the court for his 272-day sentence. At this point, his supporters were distraught. The Chronicle stated that “a woman seated at the back of the Court yelled and was promptly ejected by the Police for adopting such means of expressing her sorrow.”

The Chronicle ended its report: “The jail gate then solemnly clanged behind the Chaplain General before any of the few remaining “soldiers” of the Church Army of America could arrive to drop a tear.” In less than two months, according to the snarky report from the same newspaper, the Rev. Claude Smith had “made a remarkable change in his garments-or garb.”

There is no continuity in the research trail and what eventually happened to Smith could not be verified but he certainly, for a brief period, left an unmistakable mark on Georgetown.