By Adrienne Rooney, Ramaesh J. Bhagirat-Rivera, Vibert Compton Cambridge

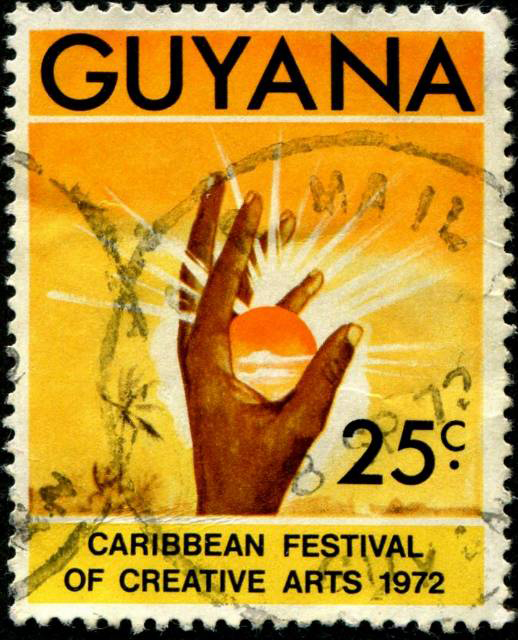

In our prior column we reflected on the motivation, organizing philosophy, and other environmental factors that determined the design and delivery of the three-day, mainly virtual international symposium to mark the 50th anniversary of Carifesta ’72 in Guyana called The Inaugural Caribbean Festival of Arts as Prism: 20th Century Festivals in the Multilingual Caribbean.

Today, we reflect on the broader historical and contemporary significance of Carifesta ’72 in relation to Guyanese and pan-Caribbean cultural policy and practice and share our thoughts on key takeaways from the symposium as we look towards the future.

The symposium offered an avenue through which to facilitate intergenerational dialogue and catharsis. Importantly, it also addressed sensitive matters, such as the cause and nature of the Indo-Guyanese boycott of Carifesta ’72; LGBTQ+ exclusion; the relationships and tensions between high, popular, and folk cultures; and the centrality of governments and the attendant politicization of delegations participating in the regional festival.

The symposium also afforded an opportunity to trace the impact of an influential strand in Caribbean social theory and intellectual history: pan-Caribbean nationalism.

Pan-Caribbean nationalism is a concept that encompasses the multiple ways in which entities and individuals in the region have envisioned and enacted processes to facilitate political, economic, and cultural unity. Guyana offers a fruitful place to explore the germination and assertion of the pan-Caribbean nationalist idea.

It was in British Guiana in 1926 that the leaders of nascent workers’ organizations in the Anglophone Caribbean met to cogitate on a pan-West Indian response to the pervasive harsh working conditions and low wages experienced by the region’s working class. Among the resolutions from their meeting was an appeal “for a federation of the West Indies with self-government and dominion status.”

Variations on that vision remained (and remain) alive in the Caribbean. These efforts have coalesced around the creation of the Caribbean Labour Congress (CLC) in 1945, the West Indies Federation from 1958 to 1962, the Caribbean Free Trade Association (Carifta) in 1968, and the Caribbean Community and Common Market, today known as the Caribbean Community, (CARICOM) in 1973.

It was this deep-rooted spirit that informed the conceptualization of Carifesta ‘72. Guyana’s cultural policies and the practices since are significant indicators of the nature of the influence of the pan-Caribbean idea in a post-colonial polity.

Carifesta ’72 was a momentous moment in Guyanese cultural policy. For one, it represented the maturing of Guyanese capacity to organize and present considerable public events and spectacles. This capacity was honed following the end of World War II during events such as Queen Elizabeth II’s Coronation and the launch of the British Guiana Festival of Music, both in 1953. Those events, along with the launch of the National History and Culture Week program in 1958, brought together a group of cultural workers united in a common task of fashioning a national approach to culture en route to independence. Lynette Dolphin, LRAM, ARCM, GRSM, with extensive experience in creating new institutions (the Schools Music Festival in 1945, the BG Music Teachers Association in 1948, and the BG Festival Music in1953) emerged as a leader of this community.

By 1965, the ad hoc committee established to launch the inaugural National History and Culture Week in 1958 had morphed into the National History and Arts Council of Guyana (NHAC). The NHAC was initially tasked with realizing Carifesta.

A multidisciplinary group of artists and intellectuals from the Caribbean and its diaspora had crafted the vision of and recommendations for the festival at the Caribbean Artists and Writers Convention held in Georgetown in February 1970. After the Convention, the work to materialize Carifesta took place on the ground in Guyana and in the diaspora. As the scale of the project came into focus, the festival was delayed and a full-time organizing body known as the Carifesta Secretariat formed in the Fall of 1971. It had at least two dozen members as Carifesta approached. The challenge of accommodating hundreds of artists, not to mention overseas festival attendees, contributed to the delay, and the new organizing body needed to solve this riddle. It selected what became known as Festival City—under development as part of a broader government housing scheme to house the nation by 1976— and Carifesta’s temporary “cultural community” was accounted for in the planning.

Festival City was located in what was then a suburb of Georgetown, and the NHAC’s offices in Georgetown’s National Park in Thomas Lands housed the Secretariat. Lynette Dolphin, Chairman of the NHAC, directed the bustling Secretariat, which had a staff willing to work lengthy days if necessary. Its upper management traveled across the region to meet with cultural policy teams from Haiti to Suriname to Cuba to Brazil to Jamaica.

Carifesta’s organizers faced an enormous job and a complex political environment, of which they were of course a part. They needed to navigate not only domestic politics, but also regional politics, indeed even global Third Wordlist and Nonaligned politics. The following statement by the late Rashleigh Jackson, Guyana’s Foreign Minister (1978-1990) and at the time of the inaugural Carifesta his country’s Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations, articulated the hopes percolating for many at the time: “Non-alignment was a response to a felt need of peoples for self-determination, the preservation and enjoyment of independence, as well as a system of international relations that is democratic and governed by principles of equity and justice rather than by precepts of hegemony and practices of domination.” Marked by potent ideologies of the day, each participating country/territory had its own sensitivities; at times, distinguished artists were in active conflict with administrations. Navigating these intricate, entangled, and at times fiery dynamics took tact, grit, and grace.

The work was far from done when the curtains went down on Carifesta ’72. In addition to inaugurating a recurring and roving festival, Carifesta ‘72 catalyzed policy reflections, dialogues, and initiatives within Guyana and across the region. Guyanese cultural stalwarts like A. J. Seymour and Henry Josiah, both active in Carifesta ’72, observed how the festival revealed the limitations of Guyana’s cultural policy. They highlighted how Guyana lacked the intellectual and institutional infrastructure required to support research on the Guyanese experience. They hoped to improve the development of technical skills in the creative arts, and they aimed to encourage and nurture creativity and innovation. For example, in his report on Cultural Policy in Guyana that was submitted to UNESCO in 1977, Seymour wrote how Carifesta “showed the need for Government sponsorship in many areas if the vitality of Guyanese music, dance, drama, literature and art was to be ensured.” He also focused on the need for Guyana to build a physical infrastructure that would facilitate Guyanese cultural activity beyond Georgetown, including building facilities and centres in New Amsterdam, Linden, Anna Regina, Corriverton, and Uitvlugt (among other places). This, in Seymour’s opinion, would allow Guyanese culture to flourish.

This optimism and vision translated into many cultural initiatives. In addition to the National Cultural Centre—which was built for Carifesta and completed in 1976—a Folk Research Unit was established. The Institute of Creative Arts—encompassing the National School of Dance, National Dance Company, E. R. Burrowes School of Art, and envisaged to include a school of drama and music—was launched in 1975. The Guyana Festival of Arts (Guyfesta), conceived as a national counterpart to Carifesta, was created the same year. The life stories of these institutions are important indicators of the nature and scope of Guyana’s cultural policy and practice since 1972.

The fifty-year period since the inaugural Carifesta offers an opportunity to reflect on relationships between national and regional cultural policies, study the consequences of specific decisions by political leaders in both domains, and identify patterns of practice by political leaders of the culture sector. It offers an opportunity to reflect on Carifesta’s impact in respective host nations and to assess contemporary Carifesta practice.

For example: It is clear that Guyana has remained connected to the idea of culture as a key variable in the pan-Caribbean idea. Guyana has participated in all Carifestas since 1972, and it hosted Carifesta again in 2008, with Dr. Paloma Mohamed as Artistic Director. The Special Projects Unit—a permanent mechanism within the Ministry of Culture established since 1992 to organize the annual Mashramani celebrations and other public programs—and an ad hoc Carifesta 2008 Committee realized this tenth edition of the festival. Today, Guyana’s cultural policy is under the authority of the Ministry of Culture, Youth, and Sport, and most of the institutions established in 1972, many of which benefitted from regional experience and expertise, remain alive. However, most of them have not realized their potential and require revitalization and more funding to fulfill their missions. A major casualty was the Folk Research Unit led by Sister Rose and established with the guidance of Jamaica’s pioneering folk researcher Olive Lewin.

At The Inaugural Caribbean Festival of Arts as Prism a strong undercurrent emerged: a desire for Carifesta ‘72’s fiftieth anniversary to revive its original spirit—without replicating its missteps and with new voices and perspectives at the table. Among the most fundamental recommendations that emerged were promoting policies that center artists; valuing grassroots art practitioners and organizers; holding nuanced conversations about regional cultural standards and the region’s myriad living, evolving cultural forms; manifesting sustainable, accessible, and transparent artist funding; propping up organizations that provide space for non-partisan cultural dialogue and presentations, and multiplying opportunities for such conversations; documenting Caribbean cultural practice for posterity; building collaborations between those living in the diaspora and the region; the list goes on. Some of these recommendations are in lockstep with those outlined during the Caribbean Artists and Writers Convention 1970 and its precursor in 1966.

As mentioned in our prior column, we envisioned the symposium as but a part of a conversation that, given the scale of the Carifesta cultural phenomenon, must be deep and wide. As organizers, we walked away with several questions. The most overarching regard how recommendations from the symposium might join efforts at national and regional levels. We have also developed more pointed questions to guide ongoing efforts that sprung from the symposium.

For instance, guided by a discussion at the symposium and with the Digital Archive of Guyanese and Caribbean Festivals, Culture and Literature in mind, we ask what a digital “repatriation” of archival cultural heritage might look like. In addition to digitizing crucial cultural resources already at the University of Guyana’s Caribbean Research Library and materials gathered through the process of co-discovery discussed in last week’s column, we are considering how the Digital Archive might enable resources central to Guyanese cultural history that are housed elsewhere, particularly in the Global North, to be accessed locally. Further, with Festival City in mind, we ask what forms of productive engagement might emerge between residents of the neighborhood and its diaspora? Can a collaboration currently underway serve as a case study for related transnational, anti-extractive efforts? Most fundamentally, how can these efforts or others that emerge from dialogues at the symposium remain dedicated to a spirit of co-discovery, resource reallocation, and a new generation of national and pan-Caribbean public histories? How can they help foster not fixed narratives and hierarchies of knowledge production but creativity, imagination, collective action, and the ongoing project of redress?