Yestreen the Queen had four Maries, the nicht she’ll hae but three

There was Mary Seaton, and Mary Beaton and Mary Carmichael and me.

Word’s gone through the kitchen, and word’s gone through the ha,

That Mary Hamilton has a wean by the highest Stuart of aa.

As she gae’d up the Canongate, a loud loud laugh gied she,

But as she gaed doon the Canongate the saut tear blinded her ee.

“Oh, oftimes hae I dressed my Queen, and pit gold in her hair,

But noo I’ve gotten for my reward the gallows to be my share.

Little did my mither think the day she cradled me,

The lands I was tae travel in, the death I was tae dee.”

– Traditional

A Red, Red Rose

O my Luve’s like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve’s like the melodie

That’s sweetly play’d in tune.

So fair art thou, my bonnie lass,

So deep in luve am I:

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

Till a’ the seas gang dry:

Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi’ the sun:

I will luve thee still, my dear,

While the sands o’ life shall run.

And fare thee weel, my only Luve

And fare thee weel, awhile!

And I will come again, my Luve,

Tho’ it were ten thousand mile

– Robert Burns

Mrs Quasimodo

I’d loved them fervently since childhood.

Their generous bronze throats

Gargling, then chasanting slowly, calming me –

The village runt, name-called, stunted, lame, hair-lipped;

but bearing up, despite it all, sweet-tempered, good at needlework;

an ugly cliché in a field,

pressing dock-leaves to her fast, stung calves

and listening to the five cool bells of evensong.

I believed that they could even make it rain.

The city suited me; my lumpy shadow

lurching on its jagged alley walls;

my small eyes black

as rained-on cobblestones.

I frightened cats.

I lived alone up seven flights,

boiled potatoes on a ring

and fried a single silver fish;

then stared across the grey lead roofs

as dusk’s blue rubber rubbed them out.

And then the bells began.

I climbed the belltower steps,

out of breath and sweating anxiously, puce-faced,

and found the campanologists beneath their ropes.

They made a space for me,

telling their names,

and when it came to him

I felt a thump of confidence,

a recognition like a struck match in my head,

It was Christmas time

When the others left,

…

underneath the gaping, stricken bells

until I wept

We wed.

He swung an epithalamium for me,

embossed it on the fragrant air.

Long, sexy chimes, exuberant peals,

Slow scales trailing up and down the smaller bells,

an angelus.

We had no honeymoon,

but spent the week in bed.

and did I kiss

each part of him

… or not?

So more fool me.

We lived in the cathedral grounds.

The bellringer.

The hunchback’s wife.

(The Quasimodos. Have you met them? Gross.)

And got a life;

our neighbours – sullen gargoyles, cowled

Saints

who raised their marble hands in greeting

as I passed along the gravel paths,

my husband’s supper on a tray beneath a cloth.

But once,

one evening in the lady chapel on my own,

I kissed the cold lips of a Queen next to her King.

Something had changed,

or never even been.

Soon enough,

He started to find fault.

Why did I this?

How could I that?

Look at myself.

And in that summer’s dregs,

I’d see him

watch the pin-up gypsy

posing with the tourists in the square;

then turn his discontented mulish’s eye on me

with no more love than stone.

I should have known.

Because it’s better, isn’t it, to be well formed.

Better to be slim, be slight,

your slender neck quoted between two thumbs;

and beautiful, with creamy skin,

and tumbling auburn hair,

those devastating eyes;

and have each lovely foot

held in a bigger hand

and kissed;

then be watched till morning as you sleep,

so perfect, vulnerable and young

you hurt his blood.

And given sanctuary.

But not betrayed.

Not driven to an ecstasy of loathing of yourself;

. . .

Where did it end? A ladder. Heavy tools. A steady hand.

And me, alone all night up there,

Bent on revenge.

. . .

I sawed and pulled and hacked.

I wanted silence back.

…

– Carol Ann Duffy

There are those in Scotland, and without, who pounce on every new opportunity or excuse to re-raise the question of Scottish independence. The vote was taken and the separatists lost. But then came the traumatic, unexpected exit from the European Union. And then came the epoch-ending death of a legendary queen. It was felt that these occasions weakened the notion of a United Kingdom.

At least this latest cry provided an opportunity to revisit Scottish literature. Like Scotland itself, this literature has had a proud history and unquestioned strength. Today, one hears very little of Scottish poetry, which does not seem to have existence or legitimacy outside of British poetry. To make things worse, the term used is English poetry, which subsumes that which comes from Scotland.

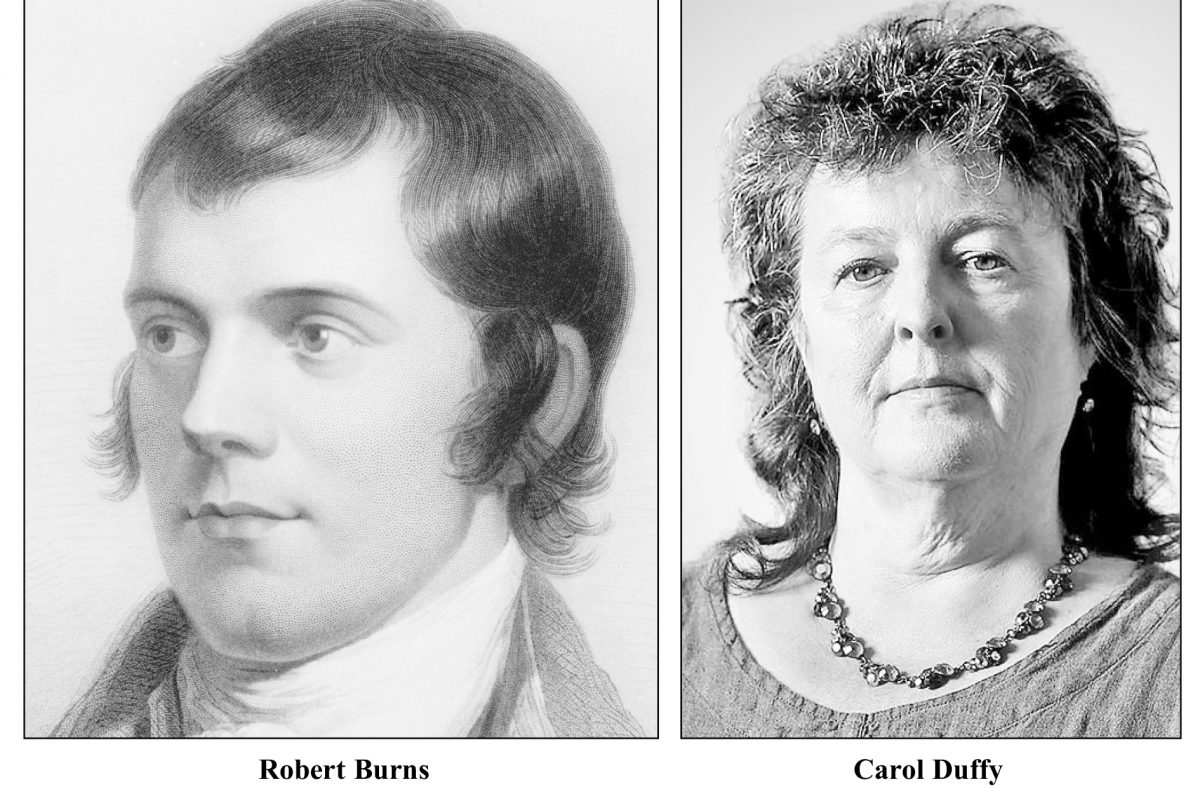

Yet, Robert Burns, who is among the best loved of Scottish poets is mostly famous for “Auld Lang Syne”. That poem, adapted by Burns from the oral poetry of the folk in eighteenth century Scotland, is sung by the whole world every New Year’s Eve. The old Scottish ballads contribute extraordinarily to the strength of English literature in which the Scots language is a major component.

That historical background, however, does not give much currency to contemporary Scottish poetry, and the new literature from that country is a far cry from the old. Most of the contemporary writers are little known outside of Scotland, and few hold a foremost place in British poetry known to the world. The outstanding exception is Carol Ann Duffy, who was appointed British Poet Laureate by Queen Elizabeth.

In fact, she holds the distinction of being the first woman and the first Scot to be appointed Poet Laureate, succeeding Andrew Motion in 2009 and succeeded by Simon Armitage in 2019. She was further decorated by the Queen and is now Dame Carol Ann Duffy. Her long, narrative poem “Mrs Quasimodo” belongs to the wave of new poetry coming out of Scotland. This verse is noted by its language – not the old Scots, but modern colloquial and popular English. Subjects and treatment are also modernist and often radical, as can be seen in the unexpurgated original text of this selection from Duffy.

The two other samples of Scottish verse printed here are from the old traditional ballads and from Burns. They help to show the historical march of Scottish poetry. The first is from traditional oral literature, and is a tragic tale from stories about Mary Queen of Scots, who had four ladies-in-waiting, each named Mary. The other is one of Burns’s best known poems and is written in Scottish dialect.