Sauda was presented in February, 2023, and by April, 2023, the plays Duenne and The Tramping Man were offered to the public. It is rare in Guyana to have two productions of this calibre seen with such frequency, and what is more, remarkable that two of the plays were past Guyana Prize winners. Those plays are not often seen on stage and this was a significant coincidence. Duenne and Tramping Man were University of Guyana productions done in partnership with The Theatre Guild; Sauda may be placed in a very special context.

Following the resurrection of the Guyana Prize for Literature, which was recalled to life in 2022 under the direction of the present government, there have been a number of notable and admirable developments. The Literary Festival was given a new place within the Republic and Mashramani celebrations and surely added cultural and intellectual strength to Guyana’s commemoration of the anniversary of Republican status, fortifying entertainment with not only variety, but instruction.

Further to that, Minister of Culture Charles Ramson, Jnr, revealed a praiseworthy initiative to have plays which won the Guyana Prize produced on stage on a regular basis. The idea is that the Department of Culture will facilitate the production of one of these plays every three months. The selection, management and performance of the plays will be done by private groups, decided upon by the local theatre community, but entirely funded by the Ministry. The Department of Culture will pay the production costs and waive the usual fees at the Cultural Centre, but the groups who actually produce and perform the plays will get all the income from sale of tickets.

This will go down as a considerable advancement and relieve producers of facing the weighty production costs and Cultural Centre fees and taxes, making it much easier for them to produce good quality drama without taking box office risks. Local theatre producers will hope that this is a step that can lead to further relief in the exacting series of fees and taxes facing producers who use the National Cultural Centre.

What it did do was allow the National Drama Company (NDC) to stage their second production of the play Sauda. Many of the prize winning plays have never been produced on stage and this scheme will put an end to that anomaly. The next play to be done in this new series will be Makantali (1976) by Harold Bascom, which is scheduled for performance during the Independence celebrations in May, 2023. The other Prize winning plays that have already been staged are The Last of the Red Men (2006) by Michael Gilkes, and Anancy’s Way (2004) by Paloma Mohamed.

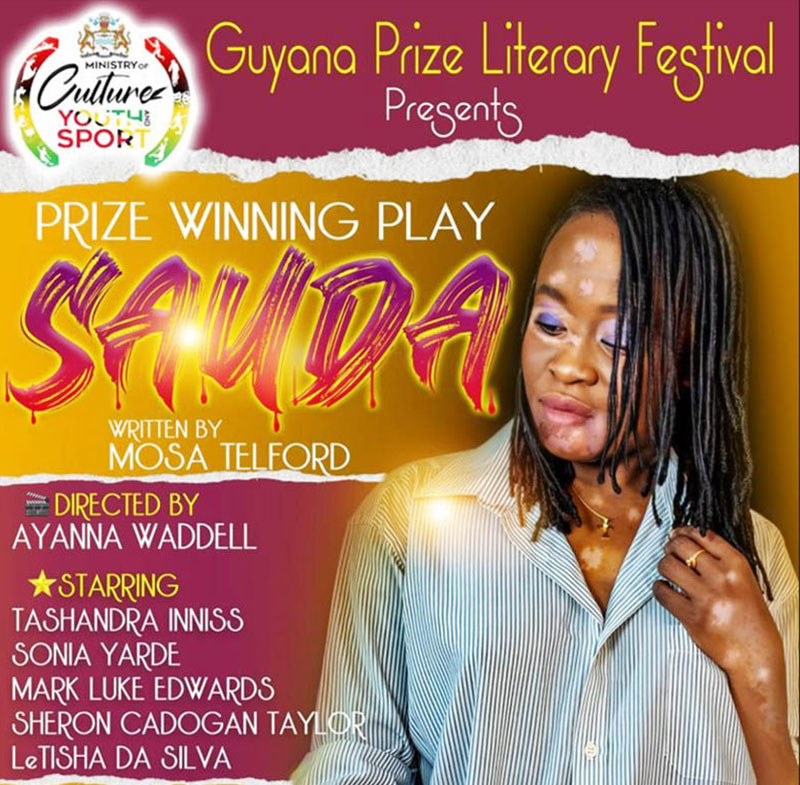

Sauda, which was first performed in the National Drama Festival directed by Tivia Collins, was on stage again when the Guyana Prize took the playwright Mosa Telford to Carifesta in Haiti in 2015 as a complement to the performance of the play in promotion of the Prize among a Caribbean-wide audience. The play was a part of Guyana’s contingent to the festival and was performed by the NDC and directed by Ayanna Waddell.

In 2023, under the same director and company, this tragic Guyanese play about colorism, self contempt, catastrophe and domestic conflict, was given a brand new lease on life. A drama written in the mode of social realism, was interpreted with its full impact on social consciousness and startlingly transformed as post-modernist theatre of the avant-garde. Waddell introduced contemporary techniques into the staging, adopting the kinds of twentieth century theatre techniques frequently demonstrated by the NDC in their productions.

In this play a naïve, simplistic, easily impressed teenaged girl, Sauda (Tashandra Inniss), is thrown out of the home by her single mother Deloris (Sheron Cadogan-Taylor) when it is discovered that she is pregnant, an outcome driven by Sauda’s secretly promiscuous life-style . The girl’s behaviour is driven by her very low self esteem and the self contempt she learns from her mother. She is black – of a distinctly dark complexion, which she is socialised to believe is ugly, a disadvantage to upward mobility, and places her at the foot of the social hierarchy. This love-starved condition, with a negative self and social consciousness driven into her by her own mother, drives her to seek love and affection, and fall prey to boys at school, then to other men who she thinks “like her”, and who offer any trifling gifts.

Against the constantly imploring advice of Esmond (Mark Luke-Edwards), the only man living in the yard, Sauda is rescued and taken in by Meri (Sonia Yarde), a professional prostitute who has her own house in the yard. But this rescue is ironic because Meri, who hates men, has designs on her – not only of a lesbian nature, but also to recruit her into the profession for extra financial gain. Meri is a foil to Sauda since she is herself a victim of past abuse, and seeks the affection and human comfort she cannot find in her professional life.

The plot is complicated by the deteriorating health of Deloris, unknown to the others, and the similarly unknown connections between Meri and Esmond’s wife Rhonda (LeTisha Da Silva) and the dramatic progressions that build towards a cloudy and tragic resolution to the drama.

Waddell highlights these through the application of the kinds of contemporary theatre techniques typical of the NDC, innovative and imaginative, that demonstrate the post-modern advancements upon realism. She introduces character/functionaries called “Shadows” (Keon Heywood, Jonathan Hamer, Deandra Daniels, Allia George) – actually dark, wistful, shadowy figures who change the set with choreographic movement and song, commentary on the action, plot and themes.

These are supported by choreography from Hamer and singing led by Heywood and Kim Samuels. Music is also enlisted to support the dramatic design, and the musical tradition used is the Kwe Kwe. Song lyrics are drawn from this folk tradition which is festive in the celebration of a wedding, but in this play, supports its tragic themes. This is possible because the Kwe Kwe is a social tradition that serves as a moral guide and a means of social control. The play deals with errant behaviour, and in its social context, the Kwe Kwe promotes chastity and is critical of errant sexual conduct. It therefore provides thematic chorus as well as a dance design for the performance.

Perhaps the most breath-taking moment in the play is when the revolving set is revealed. It is spectacular and functional and used to reveal the interior of Meri’s house. This is a revolving set that is operated by the Shadows with dance and song. Actually, revolving sets are used in western theatre on Broadway as well as in the London West End, as well as the NAPA in Trinidad, and represent the development of modern technology on stage. Those sets are motored by electronic stage technology, but the revolving idea employed by the NDC is a part of the dramatic techniques through which performers/actors/dancers turn the set as a part of their performance. It was first seen in the NDC production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest directed by Esther Hamer and Kerron Bruce.

Esther Hamer was joint set designer with Waddell for Sauda, and also the stage manager, with a supporting staff that included Kim Fernandes (props) and Akbar Singh, along with Steve Bravo and Latoya Da Silva (make-up), Godfrey Naughton (set builder), and Simone Dowding coopted as Assistant Director.

Inniss was remarkably convincing as Sauda, establishing her credentials as a lead actress in roles that demand precise characterisation and sensitivity. It was a role that she created as if she was giving a blueprint of how to authenticate the character. Inniss managed emotions and grew with the girl in the plot from frightened, helpless outcast through perplexed uncertainty and questioning, to self-assured exploiter of men, a proficient student of Meri’s tutorial lead.

Meri, herself, was precisely painted by Yarde, who created the character, giving her memorable existence and personality. It is a role that an actress can find challenging as well as fulfilling and Yarde was up to the task, with the concomitant skills. She could be hard, a product of the street, driven by materialism, but seamlessly transformed to the vulnerable and the victim. Meri came vividly alive in dominant fashion through Yarde’s accomplished portrayal.

Cadogan-Taylor was the only actress in the cast who is not a member of the NDC, but was specially brought in as a guest, along with Dowding, who is also not a member. She succeeded in handling the very graded performance that required Deloris to move from the high energy of the passionately enraged to the resignation of the physically drained towards the end. Luke-Edwards also gave adequate support as Esmond, the conscience of the play, and its moral arbiter. He commanded the stature and personality of the sympathetic observer struggling against the tide of unreasonableness. Rhonda has the distinction of a character who is not seen until the very end, but Da Silva made her alive and almost visible because of the exceedingly effective voice performance throughout. That the audience was always aware of her presence was testimony to the success of the actress.

That there was superior artistry on show was testament to the success of the production as a whole. The NDC has a mandate to advance the study of theatre in performance and to advance stage artistry in Guyana. This production of Sauda was another play that established the NDC as being on the right track towards fulfilment of that achievement. As a continuing student of the art, Waddell delivered a lesson in Caribbean theatre.