Recognition of these, particularly oral literature, is progressive and important since that was the area where national literature originated among the indigenous peoples in ancient history.

The pre-Columbian epoch

The Pre-Columbian epoch is the first period in the evolution of the national Guyanese literature. It is a lengthy period covering the time leading up to the arrival and settlement of Europeans in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. During this historical stretch, Guyana’s deepest and most substantial corpus of oral literature developed among the nine Amerindian nations within the boundaries of Demerara, Berbice and Essequibo. This consisted of the traditional myths, the spiritual chants and prayers and the verbal performance of the piaiman and the shaman.

The legends that arise from Amerindian mythology are by far the greatest store of oral literature known in Guyana, and according to some analysts, the only store of mythology in the country. There are creation myths, myths of origin and countless legends and tales. These include the origin of mankind and of the Caribs and other nations; how man came to occupy the earth and what caused the conflicts between Caribs and Arawaks (Lokono); demi-gods and heroes such as Amalivaca – tales told as history rather than fiction. Many stories are spiritual and reflect the Amerindian belief in animism. Talking animals are a staple diet in both spiritual and secular stories. Other tales of origin explain how many natural elements came into being, how the turtle came to have marks on his back or why certain beings or species are enemies. Then there is the humorous corpus of folktales in the trickster tradition. Other types developed much later to add to the treasury, such as personal testimonies, including Kanaima stories.

The colonial era

This period in the history of Guyanese literature can be very easily identified and demarcated according to date and even by the name of the writing that started it. It is the first phase of the literary period known as the colonial era. It began with English courtier, diplomat and poet Sir Walter Ralegh (1552 – 1618), who set off a colourful, profound and eternal legacy of inspiration, myth, and the imagination, but also one of plunder, with the publication of The Discoverie of The Large, Rich, and Bewtifvl EMPYRE of GUIANA; With A Relation of the Great and Golden City of Manoa, Which The Spaniards Call El Dorado, and The Provinces of Emeria, Aromaia, Amapaia, and Other Countries, With Their Rivers, Adjoining, performed in 1595 by Sir Walter Ralegh. The theme, symbol and metaphor of El Dorado have inspired literature and driven the economic quest of Guyana without end since then. Although written by a representative of the English Crown (in the reigns of both Elizabeth I and James I), it characterised the literature of the Elizabethan age particularly relevant to Guyana at that time. It was the literature of exploration, expansion and imperialism typified by the travel writings of geographer Richard Hakluyt (1852 – 1616). Ralegh wrote in that same spirit, inviting the history of colonial plunder that was to follow but inspiring a great wealth of literature that found gold, not littered all over the ground as Raleigh fantasised, but in the imagination and alchemy of an unending generations of Guyanese writers in their exploration of the symbolic El Dorado.

Not only can Ralegh’s publication be regarded as the first writing in the history of Guyanese literature, but it set the tone for the colonial era. This extended episode covered the history of the country up to the late nineteenth century and included slavery and indentureship. It was characterised by the writings of expatriates, reaching its richest period in the nineteenth century and dominated by visiting explorers, researchers and chroniclers. It was here that most of the unfathomable treasury of Amerindian oral literature was recorded and preserved in print, and local oral literature was created by the enslaved and the indentured. The two significant native poets Simon Christian Oliver, a wealthy free black and Thomas Don, a former slave, represented the literary output of black residents, while Edward Jenkins, a Briton, attempted fiction about indentured Indians.

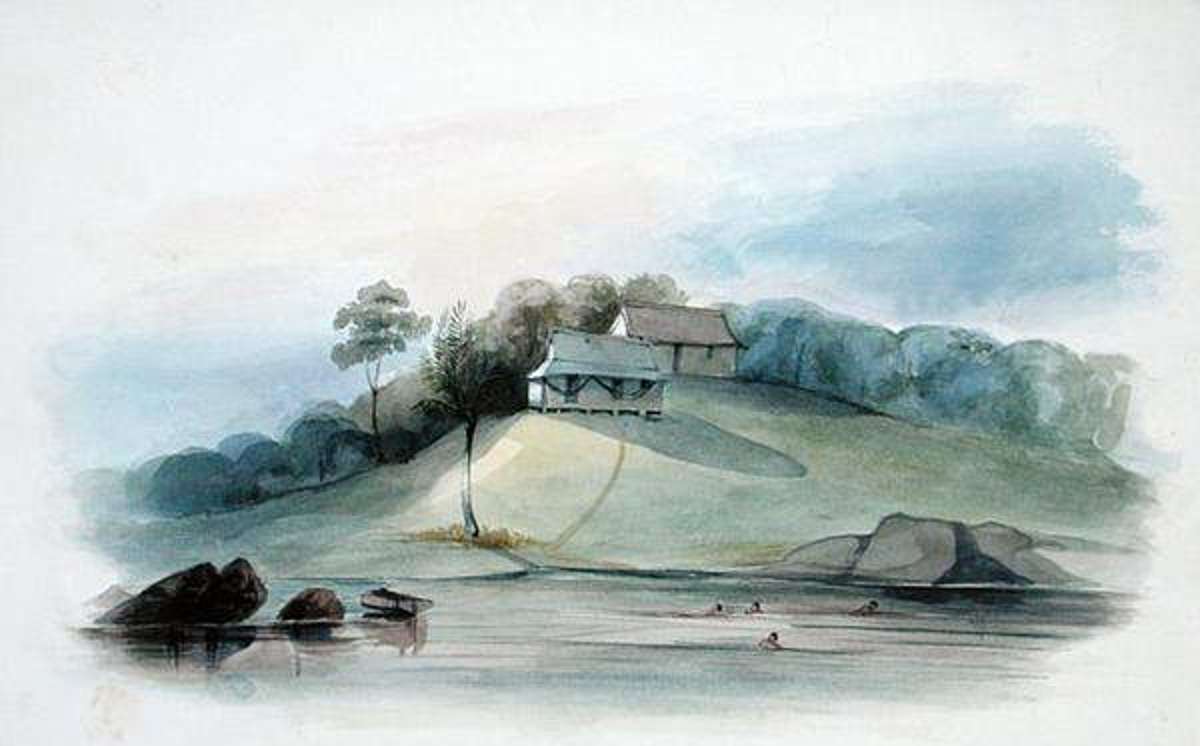

It is, therefore, a remarkable coincidence that Robert Schomburgk edited a publication of Ralegh’s Discovery of Guiana in 1848, because Schomburgk was one of the prominent contributors to the literature of this period led by visiting explorers, geographers, botanists, anthropologists, missionaries, chroniclers, colonial administrators and visual artists. Others in the nineteenth century included Everard Im Thurn, Rev William H Brett, William Hillhouse, who Prof Noel Menezes described as “a Las Casas” of the Guyana Amerindians, and Barrington Brown, who, infamously, supplied evidence to support Suriname’s claim of Guyana’s New River Triangle. Among their various interests, they were largely responsible for the documentation of Amerindian oral literature, beliefs and cultural traditions, now preserved in print. This is, however, in spite of the negative and depreciatory attitudes towards indigenous beliefs that prevailed among them. Rev Brett’s reproductions of myths remains one of the most prominent sources of this era. The work of visual artists became part of this literature because it accompanied much of the published writings. Foremost among these are the sketches of Amerindian life done by artists who accompanied the anthropologists, scientists and chroniclers. A very good example is Edward A Goodall who was a part of the Schomburgk expeditions in 1841 – 1843 producing drawings and paintings in support of Schomburgk’s work, but enough to transcend this and produce substantial independent publications.

Oliver might be the first native black Guyanese poet on record, writing at the time of emancipation. Some sources describe him as a schoolteacher in Buxton, which is questionable, since the village of Buxton did not exist until a group of freed ex-slaves purchased plantation Orange Nassau. Oliver was a free and wealthy man whose best known work is a poem about emancipation day, very colonial and unliberated in language, style and message in praise of the colonisers and of Queen Victoria. Don’s work is described by David Dabydeen as typical of slaves whose literacy and education came through the Bible, which accounted for its spiritual preoccupations. Pious Effusions (1873) was his main output.

The modern period

It was not until the publications of Egbert Martin (1861 – 1890), who wrote under the pseudonym Leo, that literature that can be identified as unmistakably Guyanese emerged. The modern period in Guyanese literature began with him, starting with his publications of poetry and short stories in the 1880s. The modern era is therefore another that can be demarcated by an actual date, publication and a particular author.

This is a complex and interesting era in the forward march of Guyanese literature, which may be divided thus: the period of imitation, the age of nationalism, the rise of social realism, pre-independence literature and post-independence literature. These will require further analysis.