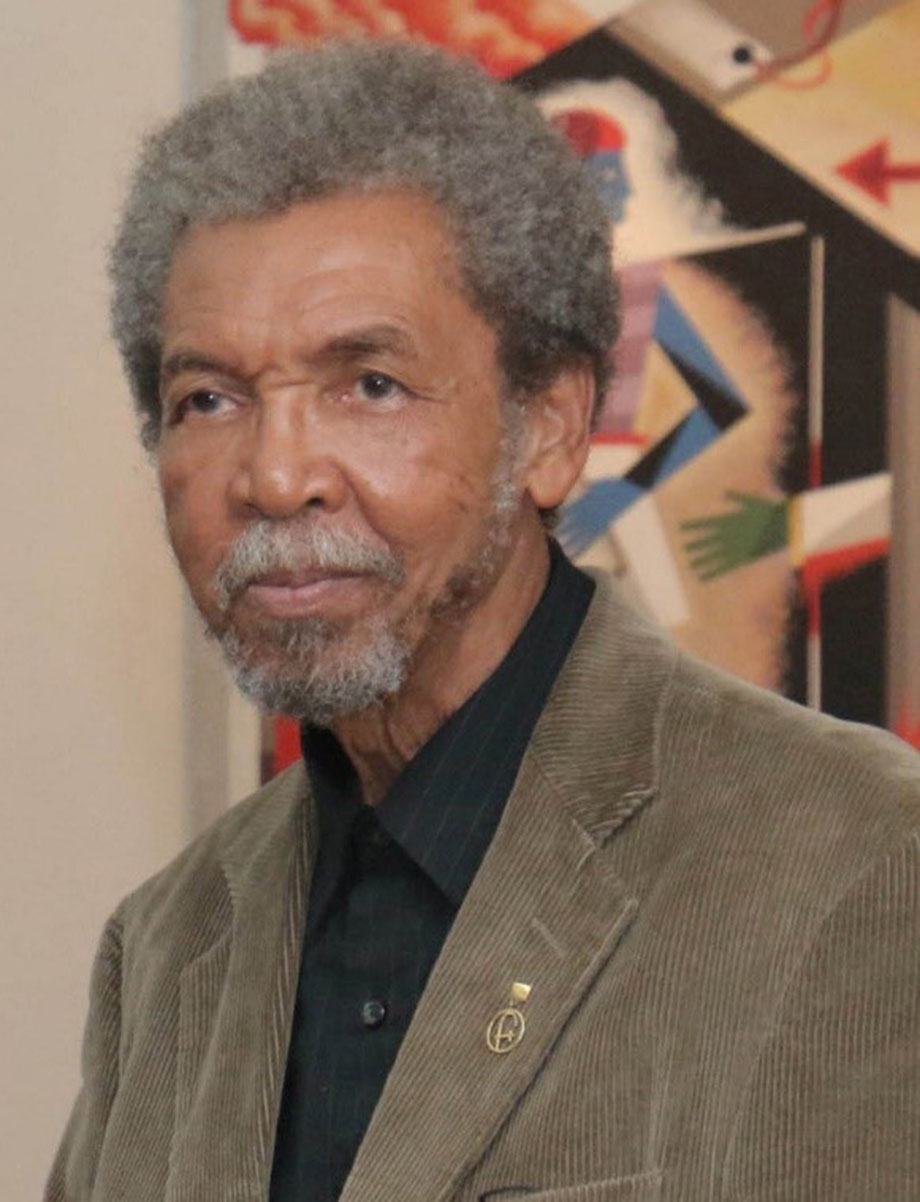

By Stanley Greaves

FRIDAY

This was payday. Waterfront workers received wages from the pay office of companies. My father’s was Sandbach Parker Ltd. Sometimes when he was working elsewhere I had to take his tag, a piece of round copper stamped with a number, to receive his pay. Men in the line seeing me in Saint’s uniform and books would ask questions about my identity. They were most pleased to see the son of one of them attending such a school and would promptly send me to the head of it as “Sweetie Greaves’ son”. I never found out how my Dad got that name; if it had anything to do with his guitar playing.

Women – common-law wives and consorts – would be waiting outside to secure household money. Most men usually went to rumshops to celebrate the end of a work week. Houston’s Rum Shop and Bar was conveniently situated in Robb Street between Main and Water streets near Sandbach Parker. Rum was chased with iced water. When my father came home I would examine his pocket. If the rounded end of a big can of sardines or salmon in tomato sauce revealed itself, I knew that he had earned twelve dollars, a good week. I eagerly awaited Sunday morning breakfast of homemade bread and chocolate tea..

SATURDAY

This day involved shopping at Stabroek or Bourda markets and the Chinese grocery in our area. The nearest to us was at the corner of King and Robb streets. Conversations between housewives and the grocers were highly entertaining. On being vociferously accused of giving short weight, the Chinese grocers would tell the housewives to go elsewhere, but everyone knew it was a game. Greens, fish and meats had to be bought each day by housewives but grownup children were often sent on such adventures on Saturdays. I was told to buy certain items from specific vendors if sent to Stabroek Market.

The British Guyana Museum, a place of great attraction (it had a stuffed lion), meant I had to stop, then run to the market buying items from one vendor. I always wondered how my mother always knew. Museum visits were allowed to take place after shopping. Some Saturdays I was sent to the Demerara Meat Company to buy ham and bacon scraps. This was a popular item and I had to attract attention by waving my list. Being a regular customer I did not have to wait long.

A popular main meal on Saturdays was cook- up rice – split peas or blackeye – accompanied either by codfish cakes and a “tomatee”, onions, garlic and fine leaf thyme sauce or stew made from one of the following: fish, chicken, or meat. Another revered dish was metagee: root vegetables cooked in coconut milk (probably of Pacific origins) with imported pig tails and salt beef (while salt beef was sold in the UK, pig tails were for export to colonies). Dry food had the same ingredients “ingreasements” (which I thought was a more accurate term) according to my Aunt Iris, but without coconut milk being used. Hassar curry was popular but did not appear often. Meals were often washed down with “swank” made with limes, brown sugar, and nutmeg. Its rivals were soft drinks if funds were available. Vimto, Portello (bottled by Russian Bear Co if memory serves me right) took pride of place before Coca Cola bottled by Wieting and Richter and Pepsi Cola by D’Aguiar.

SUNDAY

Meals prepared on this day were special. At this point the names of our mealtimes have to be explained. British breakfast was ‘tea’ for us, lunch was “breakfuss” (breakfast) and dinner was also tea. Lunch for us could be a snack: cassava pone and “swank” if you were lucky, between “brekfuss” and ‘tea’.

Tea really referred to tea imported from the UK but became a generic term as in cocoa tea, coffee tea, ginger tea or bush tea made from a variety of leaves like congo pump (my favourite), lemon grass, blacksage, mint or sweetbroom (it logically should be sweepbroom) which was actually bitter and often blended with another bush. I am left to wonder if bush tea meant it was the only kind of tea available for workers in the “bush”. These leaves were bought from specialist vendors outside Bourda Market, still there to this day. Homemade bread or fried bakes could be accompanied by a codfish stew or one of the following: codfish cakes, shrimp cakes, tinned sardines or salmon in tomato sauce, cheap white cheese or Dutchman Head – Edam cheese with a wax covering dyed red with annatto which during the Dutch occupation was acquired from the Indigenous Peoples in exchange for glass beads, steel hooks and knives.

At this point, I interrupt the narrative to relate a funny story. The first time I bought Edam cheese in London I said it was not right because it was a bit soft whereas in Guyana it has a very firm texture, not realising at the time that the texture changed during refrigeration on ships on the way to Guyana.

Bread as well as cassava bread could be toasted on the coal pot and buttered with bright yellow, salted cooking butter. When I first encountered table butter I did not like it but salted table butter was acceptable later on.

“Brekfuss” was the major meal. Soup was the traditional choice and to be really good had to include marrow bones and beef. My job was to go to Stabroek Market to a specific popular butcher, Mr Snagg, a name straight from a Dickens novel. Stuck between shouting women my voice was not loud enough but being a regular customer he would always point to me. I would name what I wanted – meat and soup bones. After meat was removed from large marrow bones, the latter would be sawn into small pieces with what looked like a giant hacksaw and often split with a hatchet. Chunks of brisket and bones were wrapped in white newsprint.

To split peas, blackeye or red bean (soaked overnight and drained) were added beef or chicken, and selections from, green plantain, cassava, eddoe, tannia, and hard yam (African origins).

The softer Chinese yam know as “bell yam” puzzled me until I did French at Saint’s and realised “belle” meant beautiful; a linguistic heritage from the French occupation. “Balanjay” is another such word from “boulanger” the French for baker. The vegetable looks a bit like the traditional French baguette or long bread.

Pounded plantains known as “Fu-fu” was also popular. It is a West African word meaning pounded hard yam. During the days of slavery in Guyana, British plantation owners had to provide food by law and this led to breadfruit and plantain trees being brought to the country and cultivated in fields. Villages referred to such areas as “plantain walk”. The walk I suspected, referred to the dam that separated fields.

Crab with shrimps (“strimps”) callaloo and ochro soup, minus marrow bones, was also a favourite dish. Ochro (ochroe) is really the anglicised word for “okra” which, related to the hibiscus plant, is native to Ghana. It is always interesting to examine the derivation and history of particular words used in any creole language.

Cooking utensils – pots and frying pans made of heavy cast iron were discarded if dropped and cracks appeared. Fuel for coal pots was wood, wallaba best of all because it was resinous and caught fire easily. Not so greenheart which gave off smoke and had to be fanned to get flames started. Coals from wallaba were reserved for heating the irons for “pressing” clothes because they created glowing heat and not flames. I learnt how to use the axe, hatchet and cutlass for cutting wood: always to use a diagonal stroke and not ninety degrees when cutting across a long piece of wood. Diagonal strokes slice the grain quickly and efficiently. The use of the left and right hook in boxing, the knockout punches, prove the same thing. Cutting small pieces of at right angles was not only inefficient but could cause chips to fly upwards and hit you.

Sunday was also the time the shout, “Enamel wares, solder” could be heard in the yard from the itinerant repairman (tinker in the UK), because he knew everyone would be at home, families as well as single men or women. His worn felt hat, jacket and denim (“dutty powder”) trousers were standard wear for the working man. “Dutty powder” was actually derived from the French “poudre bleu” (blue powder) the name of the rough blue cloth used by workers and peasants. The repairman carried the tools of his trade. There was a tin can with coals used to heat the soldering iron, an iron rod with the soldering head of solid copper shaped to a point. Copper is easily heated. A small tin of soldering paste and short lengths of solder completed his equipment. It was exciting to watch him work. Enamelled pots were light and if dropped the enamel would flake off. Any small hole appearing in a cup would be soldered. Holes in pots were a totally different matter. Solder if used would melt from direct heat. After being sanded on the exterior a file was used to widen the hole so that a small nut and bolt could be fitted with washers both inside and out. When completed he would test the pot with water.

Hardly anyone attended church on Sundays but could listen to broadcasts from Mr Cumming’s radio which he would turn up loud. The exceptions were Miss Aulder, Matriarch of the Yard, a Catholic, who attended Sacred Heart Church and John Rankin, the last son of the landlord. He was an altar boy at St George’s Cathedral. I used to observe his lengthy ritual of cleaning and polishing his black and white two toned shoes. Propert’s White and Nugget Black polish did the job. I would watch him use a bit of pointer from a broom to carefully place Propert’s White into the designed holes of the sides of the shoes. All my mother’s entreaties and encouragement to wear such shoes fell on deaf ears. I had to clean and polish my black shoes and scrub my yachting shoes – canvas top and non-slip rubber soles. These were designed for sailors but being inexpensive became daily wear for working people who knew nothing about yachts. I sometimes had to clean and polish my father’s brown shoes worn only on special occasions,

Lunch, if ever it appeared, depended on the size of the budget and could occur during any mid-week afternoon for children and on Sundays for adults. This was usually a homemade drink with cassava or cornflour pumpkin pone, or cakes bought from the shop, such as white eye, coconut buns, anise seed biscuits (my favourite when taken with milk). Tennis roll and cheese was a top-of-the-line choice. That ‘tennis” referred to the shape and colour of the roll is my conjecture because I could not see middle class and expatriates eating such rolls after games.

On Sundays in particular we all listened for two sounds from the street. One was the whistle of the ice cart man, Mr Sampson. A large block of ice from Wieting and Richter’s Ice House was in a donkey cart covered in sawdust and with a wet jute sugar bag that inhibited melting. The smallest amount that could be bought was “a cent ice” chopped from the block with an ice axe, that looked like a tomahawk with a pick at one end, and weighted in a hand-held scale. Ice was needed for homemade drinks and ice cream. The other welcomed sound was the bell of the shave-ice man. You had visions of the compressed block of shaved ice covered in a syrup based on fruits in season. As his business improved, he became known as the sno-cone man selling his product in ice cream cones. You previously provided your own container or the paper cone he provided.

The greatest delight on a Sunday would be homemade ice cream, where the debate preceding the making involved choosing between coconut and soursop ice cream. The latter usually won. I had to buy a small block of ice from the Ice House to be used in the hand-operated churn. Ice was packed around the central metal container in the wooden bucket. and coarse salt added to make it colder. This was the one job willingly undertaken by boys. The wooden paddle covered with cream after being lifted from the container was a real treat.

‘Tea’ was lighter than the morning meal. It was served with either bread or biscuits along with butter and cheese. Another funny story is that the first time I ordered biscuits in the US, I was surprised to see what looked like what I knew as a bake. I should have asked for crackers, a name obviously derived from the sound they make.

The day’s events sometimes ended with games, described in detail in a previous article. Girls skipped and boys played “bat an’ ball” cricket which was fun. The bat was homemade and the tennis ball came from those who were ball boys at the Bishops’ High School tennis courts. Balls were sometimes “lost” in hibiscus hedges bordering the courts. In our cricket game, the ball was delivered underhand and produced a satisfying sound when hit squarely. If we could see from its trajectory that it was heading into an open window, players disappeared like the wind. If, as it sometimes happened, an adult played with us he would “beg” pardon which would allow us to continue. The end of the day was signalled by calls from mothers: “Go wash your face and hands”. I could never understand why it was face and not feet when it was the latter that accumulated dust. Adults could be funny people sometimes..

In conclusion, it must be clearly stated that the meals for any day depended on the finances available. On occasion, thankfully few in number, ‘tea’ could be plain bread or biscuits and “brekfuss” a plate of plain rice with a pat of cooking butter. Having recognised the signs, one did not complain but hoped and prayed for better moments. Really joyous times could be few and far apart during the course of weeks and months. I am sure the episodes that took place at 132 Carmichael Street parallelled those that took place in similar locations in Kingston, Tiger Bay, Waterloo Street, Charlotte Street, D’Urban Street, Charlestown, Albouystown and elsewhere.