By Nikita Blair

After my Valentines’ Day readings back in February, I made a vow with myself: during 2023, I would read more of Akaweke Emezi’s work. I began this endeavour with “You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty”, Emezi’s titillating romance debut featuring two bisexual lead characters and their struggles to find happiness and love after traumatic events in their lives. I loved this book, and it inspired me to read more of their work this year.

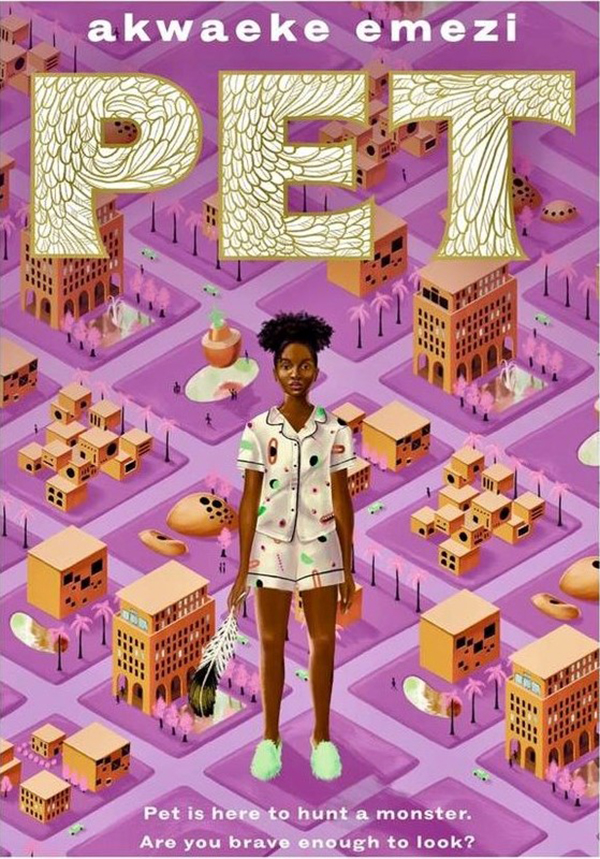

So, as Pride Month comes to an end, I return to Emezi. This time, I’ve chosen their young adult debut novel “Pet”, published back in 2019. “Pet” is a deceptively slim volume. Within its relatively short page-count, it explores weighty topics such as utopias, community health and the evils that can lurk and thrive in seemingly perfect societies. And in true Emezi fashion, this book thrilled me in unexpected and wonderful ways.

“There shouldn’t be any monsters left in Lucille… They used to be everywhere, thick in the air and offices, in the streets and in people’s own homes. They used to be the police and teachers and judges and even the mayor; yeah. The mayor used to be a monster.” – p. 1

Lucille is a utopia. At least that’s what Jam was taught to believe. Long before she was born, the world fought to rid itself of monsters great and small, subtle and overt. The ones instrumental in this revolution were branded angels by the people of Lucille. Even though it’s an open secret that Lucille’s angels had to do monstrous things during the revolution, many of them now hold leadership positions in the city and the citizens hold them in high regard.

Jam herself is proof of Lucille’s safety and inclusiveness. She’s a transgender, neurodivergent teenager, the daughter of a hardworking paramedic named Aloe and an artist named Bitter. Early in the story, Aloe admits that Jam’s differences would have made her an outsider and a target for violence. But here in Lucille, she’s just a regular person, a part of the diverse mosaic of life in a city dedicated to equity and accountability.

But Jam’s worldview is about to be challenged. A creature calling itself Pet has crawled out of Bitter’s newest painting, claiming that there’s a monster hiding in Jam’s best friend’s house. Pet’s sole purpose is to find and destroy it. Jam, understandably concerned, wants to help, but when Pet explains its intention to her parents, they encourage Jam to dismiss it, claiming that it must be mistaken because there are no more monsters left in Lucille.

Jam has a choice. She can either listen to her parents and risk keeping her best friend, Redemption, in danger. Or she can err on the side of caution by accompanying and assisting Pet on its hunt to protect Redemption. Jam chooses the latter, breaking out of her parents’ cocoon of security and ignorance to go monster-hunting with Pet. As the days pass and the pair get closer to uncovering the mystery, Jam is forced to face the truth of Lucille: monsters can look like anybody, goodness isn’t always pretty, and doing the right thing can be difficult, even painful.

The right to be mundane

I chose “Pet” for my Pride month reading because Emezi does something that I have only seen in a few other books thus far: they’ve given their queer and neurodivergent character the right to be mundane.

Lucille is a utopia, and no one embodies the epitome of its safety more than Jam herself. Jam is a transgender teenager and is selectively mute, preferring to use sign language rather than speaking out loud. She also seems to have sound and vibration sensitivities, which enable her to sense everything going on in her house by just touching the floorboards in her bedroom.

Despite Jam’s differences, she is welcomed and loved in her community. No one tries to make her feel like she’s an outsider. Instead, we see how her parents, best friend, and many members of her community make her feel welcome by learning sign language to communicate with her, and just accept her as a queer individual. The story doesn’t rotate around Jam’s neurodivergence or transness. Her identities are accidental. She is simply mundane in this world.

This mundaneness shows what the angels of Lucille were fighting for: a place where everyone, regardless of race, age, gender, or physical or mental ability could be safe, cared for, loved and in community with a mosaic of diverse peoples. The way Emezi presents this future makes it feel very warm and welcoming indeed.

Hunting monsters

“… The problem is, when you think you’ve been without monsters for so long, sometimes you forget what they look like, what they sound like, no matter how much remembering your education urges you to do…So yes, people forget, but forgetting is dangerous.

Forgetting is how monsters come back.” – pp. 19-20

As a teenager, Jam has a lot more growing up to do. But she never expected that hunting monsters with something like Pet would be instrumental to her development.

And Pet steals the show in all its scenes in this book. I love Pet as a character. It’s a righteous, menacing, determined force of good and justice bundled into a grotesque package that confuses and intimidates Jam at first. She’s been cocooned by her parents and Lucille’s system all her life and thus developed a black-and-white way of thinking about good and evil. Pet inverts this worldview, its appearance directly challenging Jam’s idea of what “good” should look like. And while they hunt together, Pet actively challenges Jam to look beyond the normality and familiarity of her world’s surface to uncover the rot hidden within. Only when Jam begins to think outside of her presumptions is she able to be a true asset on the hunt.

The monster hunt shatters Jam’s innocence, but it does so in a way that doesn’t steal anything from her. Instead, it gives to her, expands her horizons and makes her embody the true ideals Lucille is supposed to stand for. It was an absolute delight to read this coming-of-age arc in this story.

Justice as community health

“We are each other’s harvest. We are each other’s business. We are each other’s magnitude and bond.” – p. 14

“Pet” is many things. It’s a coming-of-age story. It’s a utopian story. But at its core, “Pet” is about community health. Lucille is a city dedicated to caring for its inhabitants in ways that ensure that everyone can survive, thrive and live their lives to the fullest. It has eliminated many social issues — bigotry, disability discrimination, various forms of abuse, corruption, etc — and made itself a safe and accepting place for a diverse group of people. As such, girls like Jam can grow up without the traumas of hatred and rejection.

Every person in Lucille is taught that their actions have consequences, and they are responsible for the health and wellness of their community. To maintain this paradise, everyone needs to care enough for their friends, families, and strangers to prevent the growth and development of monsters.

Jam’s hunt is not just a simple good-versus-evil kind of deal. Jam’s hunt is a way for her to give back to the community that nurtured and protected her, making Lucille even healthier and safer than it was before. But she can only accomplish this because she cares fiercely for Redemption and makes him and the monster in his house her business.

That was what I loved about “Pet”. It’s a fun, short read, but also aims to tell its young audience that in order to build a better, equitable future, you don’t just need to get rid of all the world’s problems. You have to care enough to prevent those problems from resurfacing. And if they do, you have to be brave enough to admit that the problem exists and find new ways to tackle it all over again.

Conclusion

I thoroughly enjoyed “Pet”. I’ve actually read it twice: once for the story and this review, and another time for the sheer pleasure of enjoying a well-written piece of literature. “Pet” is a story with a big heart; a tale that threads warmth, concern, and care for the world and its people into every word. It’s an excellent Pride read for anyone who wants a story about a queer character just existing and being a normal part of their world before being thrown into a bizarre adventure. “Pet” does deal with heavier topics, but Emezi presents these in ways that aren’t jarring or traumatizing. They handle these topics with as much care as the average Lucillian, making this book an easy and enjoyable, yet weighty and thought-provoking read.