In 1960s Guyana, a woman from Albion had recently returned from Mecca, which is considered Islam’s holiest city. Her trip held significant importance for the entire country, as she had not been vaccinated for smallpox and unwittingly brought the disease back with her. Panic spread throughout the nation as news of her infection and the potential outbreak circulated.

Since she was a resident of Albion, it became the responsibility of the Port Mourant Hospital in Berbice to attend to her. Tasked with containing the illness, Dr Chet Bahadursingh, who headed the Port Mourant Hospital, placed the woman under quarantine until she recovered. Fortunately, she made a full recovery and the sickness was contained, bringing relief to the country. The doctor earned a reputation as one of Guyana’s best.

He solidified this reputation when he saved approximately 80 children from succumbing to gastroenteritis at the Port Mourant Hospital. At the Georgetown Public Hospital (GPH) dozens of children, mostly infants, were succumbing to the illness every week. Dr Bahadursingh only lost three patients, one of whom had arrived at the hospital in a critical state.

Perplexed by the high mortality rate at GPH, a public health official visited the Port Mourant Hospital and inquired about his methods. Dr Bahadursingh explained that the babies required constant fluids. Working night and day, he ensured that the needles inserted in them remained securely in their veins, even during their frequent movements. The authorities were impressed by the simplicity and effectiveness of his methods, and offered him the position of chief medical officer at GPHC. However, he declined the offer, believing that his services were still needed at the Port Mourant Hospital, an establishment he had helped renovate to better serve the community.

Dr Bahadursingh had studied in India and upon his return, he was disappointed by the state of the building and the doctors at the hospital. He described the hospital as shabby and the doctors working there as more concerned with making money than caring for patients. He revealed that bribery was commonplace in the hospital. As the head of the Port Mourant Hospital, he took two steps to address this issue. First, he approached merchants in the community and asked for funding to improve the hospital, transforming it into a decent facility. Second, instead of accepting bribes, he requested people to contribute the money they would have paid as bribes into a box. This accumulated money was then used for further construction and enhancements at the hospital. Today, the Port Mourant Hospital continues to serve the residents of the community.

Becoming a doctor was not an easy path for Bahadursingh, especially given the class and racial structure of Guyanese society in the 1960s, where most institutions were still under British control. The Indians on the sugar estates were mistreated by the British and many saw education as an escape for their children. They saved money and aspired for their children to become either doctors or lawyers, as these professions could lead to private practice.

Bahadursingh dreamed of becoming a doctor. He applied to schools in the United Kingdom and received responses stating that while his grades were excellent, he needed to complete A-levels. At that time, only Queen’s College and the Bishops’ High (then an all-girls’ school) offered A-levels. These schools were reserved for the highest social class and accepted only a few students outside of that bracket.

Bahadursingh wrote to the Education Department in Georgetown, expressing his dream of becoming a doctor and requesting to sit the A-level examinations. The response he received said, “We do not think you are capable of becoming a doctor.” He accepted what he was told, considering himself an ordinary boy from a village but kept the letter as motivation to prove them wrong; it was only recently that he misplaced it.

In the meantime, he took a teaching position at the Ramlochan High School, which is now the Berbice Educational Institute. The school catered to students who were not performing well at Berbice High School. Bahadursingh taught there for two years. Later, he attempted to secure a job at a sugar estate but was informed that he was overqualified for the available positions. Seeing this as a sign to further pursue his studies and become a doctor, Bahadursingh contacted the Indian Embassy in Trinidad, which provided him with a list of universities in Bombay (now Mumbai). With financial support from his grandfather and father, he prepared to leave Guyana for India. He had never even left the county of Berbice before. At the age of 21, it would be his first time on an aeroplane. The journey was not without its challenges.

He flew to New York and then got on a ship to London. Upon his arrival in London, he faced rejection when looking for lodging. He recalled being told by a white woman that no coloured people were allowed and he noticed a sign saying, “No Blacks or Irish.” Eventually, he remembered a hostel for Indians and went there, although, initially, there were no available rooms. However, the landlady kindly allowed him to wait, assuring him that once a room became available, he would have a place to sleep for the night. Bahadursingh attributed the problem to the United Kingdom’s backwardness rather than his skin colour. The trip to India took two weeks.

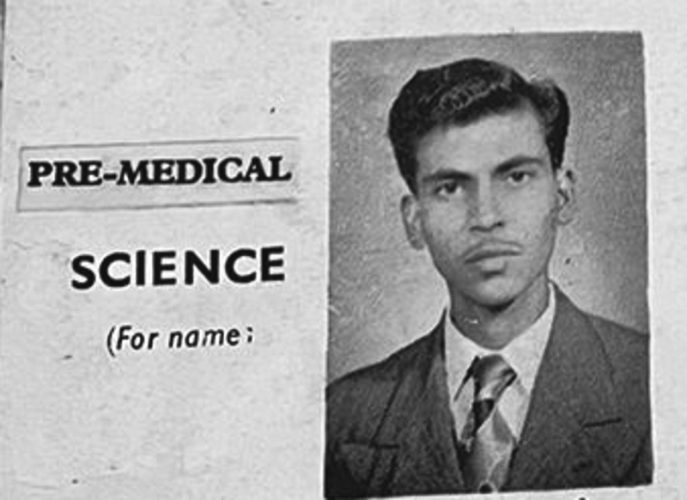

At St. Xavier’s College at the University of Bombay, he studied physics, chemistry, and biology. Two years later, he sat his examinations. During one of the exams, he became so nervous that he erased parts of his paper. When the time to hand in his paper arrived, his mind went blank and he forgot what was erased. It caused him considerable anxiety about the results. His dreams were on the paper and failure would bring an end to that dream, Bahadursingh expressed. When the results were eventually posted on a placard, he anxiously searched for his name at the bottom. It was then that a friend, who had been his study partner since the beginning, asked what he was doing. “Looking for my name,” he replied, only for his friend to inform him, “You fool, look at the top!” Bahadursingh’s voice cracked with emotion as he recalled the revelation that he had achieved the top position in his studies.

He secured a place at Grant Medical College in Mumbai, graduated with honours, and completed his internship in India. Returning to Guyana as a doctor, he proved his detractors wrong. However, his journey was far from over.

Due to the political climate in Guyana at the time, he couldn’t lead a simple life as a doctor. After working for a year at Georgetown Public Hospital, he requested a transfer to Berbice, where he began his service at the Port Mourant Hospital. During this period, tension and violence between Africans and Indians were prevalent and racial violence plagued the Port Mourant community. He recalled having to hide Africans in his hospital to protect them from a hostile community that intended to harm them physically. He himself became a victim of political interference.

He remembered that then president Arthur Chung had decided to pay a visit to the Port Mourant Hospital. Bahadursingh said he asked for the president’s photograph to be displayed on the wall, to signify his visit. Subsequently, then prime minister Forbes Burnham visited the hospital, saw the photograph on the wall and inquired why his photo wasn’t there. Bahadursingh recalled saying, “Mr Chung is the president and you’re just the prime minister.” This incensed Burnham, leading to Bahadursingh being transferred to Suddie in Essequibo. Not wanting to move his family to Essequibo, he elected to go into private practice. However, he had become a target for the government, and this led to him being strip searched whenever he left the country.

Realising it was time for a change, he looked around and discovered that the Government of Barbados required a doctor with his qualifications. He moved to Barbados, where he experienced the joy of working in an environment where he was treated well and respected for his skills. When he reached the age of retirement, he was urged to continue working, becoming the oldest doctor on staff and receiving both his salary and pension. Eventually, he retired at the age of 80 and now mostly resides in Guyana.