Anil Persaud is a street historian.

The flute in question was discovered by archaeologists in the Divje Babe cave near the Idrijca River in Slovenia in 1995 and dates back sixty thousand years to the Neanderthals. It was fashioned from the left thigh bone of a young bear. Edgar Mittelholzer was on to something after all, with his 1955 novel My Bones and my Flute: A Ghost Story in the Old-Fashioned Manner, a reminder of the interest in Warao, Arawak, Macusi, Carib and Wai-Wai flutes as objects of inspiration and study.

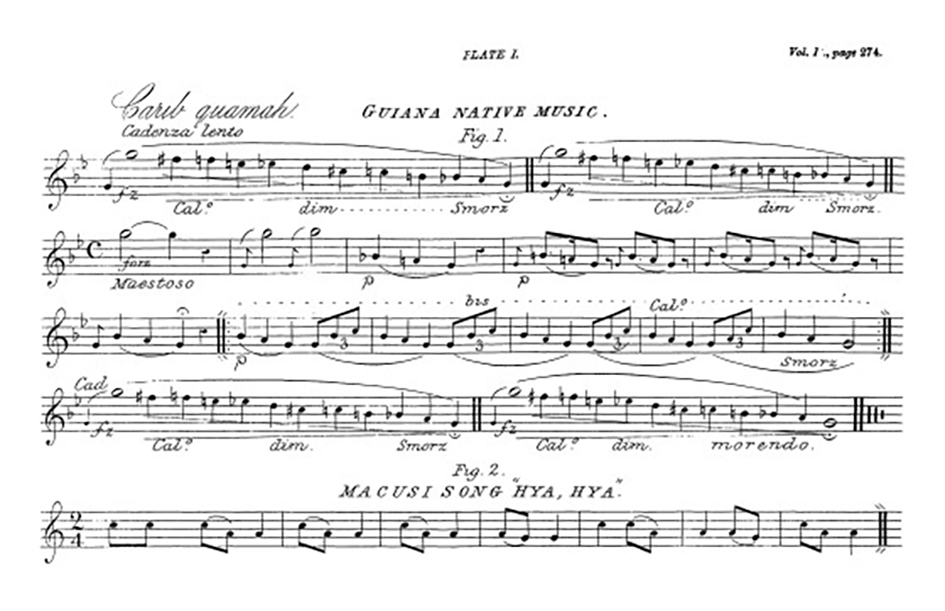

Carib Quamah & Macusi Song “Hya, Hya”

In the wake of the Mahdia fire that claimed the lives of 20 students, now may be the time to share these two pieces of music. In written and recorded form they allow us to both audibly hear the past and also break present silences.

They were written down by the same imperial cartographer who drew the lines that give Guyana its distinctive shape, Robert Hermann Schomburgk, and included in an 1844 lecture delivered to Britain’s Royal Geographical Society.

There he noted, “the Indian tribes whom I have had the opportunity of becoming acquainted with […] possess several instruments, chiefly flutes, made upon primitive principles, some of reeds or bamboo, others of the thigh bones of animals.” His primitive ideas of primitivity aside, in his lecture Schomburgk told a most poignant story associated with the flute and the piece of music he unimaginatively called the “Carib quamah.” It is about a parent, in this case a father, mourning the loss of his child, maybe a daughter:

Irai, the chieftain of the Caribs, before he was converted, lost his child in 1835 at the Rupununi. I became about this time acquainted with him, and as we sojourned for some weeks at his settlement, I heard him generally singing words in a melancholy strain. I asked him the signification and he told me he bewailed his child. The words were addressed to the child in the grave:-

“Come, dear child, to me. Come out a little; let us speak together. Why do you not speak to-day? I hear the flute of Donkaba Waehra. It is your uncle’s flute which sounds; come out a little before your uncle comes.”

Schomburgk was oblivious, however, to how seamlessly the lines and bars of mourning music that he wrote down in 1835 cross fade into the national border lines he drew, that would cut off peoples and cultures on the one hand and the iron bars used to trap, imprison and extract in the name of justice, protection and development on the other. The ironies are multiple and deafening.

Donkaba Waehra’s flute, the quamah, Schomburgk explains,

is a hollow flute of bamboo, of peculiar construction, and mostly in use among the Caribs. The Carib sounds it as he approaches his home in token of his arrival; and, as in the silent woods, or among the mountains, it is heard at a considerable distance, preparations for his reception are immediately made. The music is peculiar, and, probably descended for ages, is characteristic of that wildness which has rendered the Carib so formidable.

In place of the child’s voice then, there was the sound of the flute, playing a piece of music that rests in silence, on the page. The page may not be a musical instrument, but it can be a musing instrument. Will someone share the Carib Quamah played on a bamboo flute?

My Drum and my Flute

Schomburgk, who left us Donkaba Waehra’s tune on the page, died in 1865 and, curiously, aside from the throwaway line, “the Caribs and Wapisianas, avail themselves of drums,” he said nothing about drums.

In “‘A Sadness I Can’t Carry’: The Story of the Drum,” the Ojibwe writer David Treuer, tells of the ‘Big Drum’ as a site for “gathering to mourn, to process grief, to understand loss.” Of Blackfeet heritage, the actor Shaun Taylor-Corbett’s reading of it is certainly worth listening to. At the center of Treuer’s personal reflection is the drum. Twice a year it convenes the “large, loud, social healing ceremony” known as Big Drum and into it pours histories, of violence against the first peoples of the Americas. When healing and history meet they often speak of childhood and children. They tell powerful stories like the one Australian rules footballer Adam Goodes recently told about childhoods, his and his mother’s, as well as of the girl who once called him an “ape,” and then apologised.

I particularly like Treuer’s vignette from his time as a “drumheater;” it reminds me of childhood. The drumheater, Abiigizigewinini, he writes,

was an important position. We are the only ones allowed to physically move the drum from the home of the owner to the dance hall. We are the first to arrive at the ceremony and usually the last to leave. The dance can’t proceed without our contributions and approval. Being there first, staying last, being present — that has become my duty.

My grandfather was a drummer in his community and on more than one occasion I served as a “drumbracer”: the kid who sits on the other side of the drum, bracing, to prevent it from slipping away from the drummer. Bracing, late into the night, the beat of the drum against your back, from time to time synching up with your tiny heartbeat, kids notice stuff like that and feel wiser for it. Like the drumheater, the drumbracer was also an important position, an experience to be felt, in the bones.

Music and Emotion

Musical instruments through the music they emit are the uncanniest of historical artefacts. Like oceans in a seashell, the instrument and the sound, like the drum and the flute, are eerily intertwined. Strike the skin of a hundred year old drum, pluck the tongues of an eighteenth century Marimba and their sounds turn out answers and questions enough to make your head spin. That effect could certainly be felt when listening on Youtube to the Slovenian musician Ljuben Dimkaroski play Tomaso Albinoni’s famous ‘Adagio in G Minor’ on the sixty thousand year old ‘Neanderthal flute.’ Dimkaroski should have played the ‘Carib Quamah’ instead.

In the wake of the Mahdia fire, however, the drum and the flute have much to say, about music and emotions. For instance, a line can be traced from Homer’s prescription of music as an antidote for sorrow to today’s music therapy. For the many young voices silenced by the Mahdia fire, and for the many others, young and old, struggling to speak in its aftermath, it is our hope that the piano recordings of “Carib Quamah” and “Macusi song Hya, Hya” (please search for same on YouTube) may be a source of inspiration, strength and courage in these difficult times. Behind those bars of music, among the heavy, falling tones of grief and mourning swell insistent notes of play, bursting at times into justifiable outrage.

Along with mourning, music has a long association with political emotion as well, be it the drums that started the St. Domingue revolution or their role in the founding of the Thunder Mountain Singers drumming group of Thunder Bay, Canada. The flute, on the other hand, is its own can of worms. Plato condemned it, Krishna seduced with it, the Pied Piper reshaped it into a fluteful of questions. What was the tune that the Thracian flute-girl played that finally changed Plato’s mind or the melodies Krishna and the Pied Piper played that caused others to move? We are left to speculate. The answers that come from drums may be to questions that come from flutes.

Of Students

The two phrases that make up the title to this article are not my own. They are each taken from academic obituaries. Always difficult to write, academic obituaries, like any other, are easiest when written at the end of a long life; they are most difficult for students.

That famous collection of disappointed hopes is taken from Charles Albert Browne Jr.’s academic obituary for British Guiana’s Department of Science and Agriculture chemist John Burchmore Harrison who died in 1926. In an unusually moving section, Browne Jr. writes:

The museum of “Mare’s Nests,” which he kept in his office, will never be forgotten by anyone who has seen that famous collection of disappointed hopes. [A ‘Mare’s Nest’ is an archaic expression that refers to an ‘illusory discovery,’ something wonderful that turns out not to be real.]

There is a danger of the students who died in the Mahdia dormitory fire being turned into another ‘famous collection of disappointed hopes.’ That danger is present in the talk of ‘full compensation’ for lives lost to what is a failure of leadership. It is a danger compounded, should that compensation be paid for with profits earned from the very oil that burns the planet, fuelling fires worldwide, including Guyana. If there ever was a collection of disappointed hopes that deserve to be made famous, it is a leadership that rushes to punish a fifteen year old girl in the case of the fire at Mahdia (the only person held accountable two months after the devastating tragedy) but bends over backwards to deny justice to a sixteen year old girl in the case of alleged rape by a sitting Minister.

The second phrase, a change of the will, also written on the occasion of the death of a scholar, opens up a nest of a different kind. It speaks as much to mourning as it does to the purpose of scholarly life. Of the former, the writer reminds us that when faced with a “failure of the will” the only fitting response is “a change of the will.” The Mahdia fire must first be recognized for what it is: a failure. A failure of generations of top down, paternalistic, oligarchic leadership. The path of this model, strewn with failures, leads to a cliff where lip service masquerades as public service. The community of scholars lost twenty of their own on the night of May twenty first, 2023. We mourn them by reminding each other that to think means to think of and to think with. That is our way of ensuring that the fossilised promises of change do not yield another famous collection of disappointed hopes but result instead in a change of the will.