The effects of rising temperatures continue to take a toll in several countries. Some 20,000 residents from the city of Yellow-knife and surrounding areas in the Northwest Territories of Canada are being evacuated, because of the threat of wildfires. As of last Friday, these fires were within ten miles of the city. They have since crossed over to British Columbia, a neighbouring province to the south where a state of emergency has been declared and some 35,000 residents ordered to evacuate their homes. And in the Hawaiian island of Maui, the death toll from wildfires has risen from 80 to 111.

In last week’s article, we discussed Guyana’s elevation to the status of a high income economy, its increased borrowing limits and the implications for the country’s public debt. Today’s article concludes our discussion on the subject.

High income status vs the plight of the majority of citizens

With a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of US$15,050, Guyana has been elevated to the status of a high income country. Using the United Nations classification, Guyana is also now considered a developed country. However, there is hardly any person experiencing living in Guyana who will disagree that the country has a long way to go for it to be categorized a developed one.

The GNI is calculated using the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), adjusted to take into account inflows from Guyanese citizens and businesses from abroad as well as outflows by businesses and investors from other countries. Once a country’s GNI has been calculated, it is divided by that country’s population to determine its GNI per capita. Considering the relatively small size of Guyana’s population vis-à-vis its vast natural resources, including large offshore oil and gas reserves, the resulting calculation yields a high GNI per capita.

According to the World Bank, Guyana’s high income status is primarily due to the country being a major oil-producing nation. This is despite the fact that there has been a substantial increase in outflows of primary income abroad. Real GDP was estimated to have increased by 57.8 percent in 2022. The Bank, however, cautioned that, while the GNI is considered one of the most important at-a-glance assessments of a country’s economic health, it offers little insight into a country’s income inequality.

Guyana’s GNI per capita is 4.35 times the private sector minimum wage of G$60,147 per month. On the Human Development Index, which measures a country’s progress in health, education and standard of living, among others, the country ranked 108 out of 191 countries in 2021. The World Bank’s latest assessment is that 47 percent of the population live on less than US$5.50 per day which is threshold for upper-middle income economies. Considering the above, one therefore has to exercise caution in interpreting the Guyana’s high income status as a measure of economic and social well-being of the country’s citizens. While it is understandable that policy makers take pride and delight in referring to Guyana being one of the fastest growing economies in the world with unprecedented growth, they need to seriously reflect on what this all means to the majority of the population who have to grapple with low wages and salaries, the high cost of living, and general living standards. Of particular note is the fact that the GDP growth of 57.8 percent includes growth from the production of oil and gas, 87.5 percent of which does not belong to Guyana. While foreign investors and overseas-based Guyanese may find policy makers’ pronouncements a positive indicator and an incentive to invest in the country, the plight of the ordinary Guyanese needs to be taken into account, hence the need to temper expectations.

Considering the volatility of oil prices and the risk of unforeseen events that may have an adverse effect on oil production, two main issues need to be tackled. The first is to ensure that the economy is sufficiently diversified to withstand any possible shocks arising therefrom. At the moment, the economy is not doing well in terms of non-oil production, as indicated in the latest Bank of Guyana report. According to the Bank, the economy recorded mixed output performances in the major sectors during the first quarter of 2023, with the non-oil economy experiencing moderate growth. While there was increased production in relation to sugar and rice due to favourable weather conditions, forestry, bauxite, gold, and quarrying and mining recorded declines.

The second issue relates to climate change. According to the World Bank:

Guyana is at high risk of climate induced hazards, including increases in heavy rainfall and related occurrences of flooding, sea-level rise and storm surges, especially in coastal areas’. Research shows that the impact of rising sea levels and intensified storm surges in Guyana would be among the greatest in the world, exposing 100 percent of the country’s coastal agriculture and 66.4 percent of coastal urban areas to flooding and coastal erosion, with potential GDP losses projected to exceed 46.4 percent.

Revisiting the lifting of the ceiling for the guarantee of loans

Included in last week’s discussion was the recent lifting of the ceilings for the public debt to $750 billion and $900 billion in terms of internal and external borrowings, respectively. We also referred to the Guarantee of Loans Act where the ceiling of $1 billion was increased in August 2013 to $150 billion to give coverage to the Power Purchase Agreement between the Guyana Power and Light Inc. and the aborted Amaila Falls Hydropower Project. We stated that in May 2018, the Minister of Finance entered into a loan guarantee in the sum of $30 billion, via the issue of bonds, to assist in the restructuring of the Guyana Sugar Corporation Ltd., thereby further increasing the ceiling for the guarantee of loans to G$180 billion.

Former Minister of Finance Winston Jordan has clarified that the ceiling under the Guarantee of Loans Act had in fact not been increased. He explained that the new ceiling of $150 billion precluded the guarantee of any other project or activity of a public corporation or company by the Government. As a result of this action, Government guarantees of future projects as well as existing projects already guaranteed would have been placed in jeopardy. In 2018, the Government had decided to guarantee the bond. Since the raised ceiling for the Amaila Project was never used, it was decided to amend the Act by including the words “and other developmental activities” after the word “Project”, thereby ensuring coverage of the bond and restoration of coverage of previously covered corporation projects. We thank the former Minister for his clarification on the matter.

Further analysis of the overdraft situation

In last week’s article, we also stated that the Authorities had decided to liquidate the overdraft of $171.479 billion on the Consolidated Fund as at June 2021, through the issuance of 85 variable interest rate debentures with a total value of $200 billion. The residual amount of $28.521 billion was used as supplementary domestic financing of the Budget. The former Minister is, however, of the view that there is need for further clarification and elaboration, which we set out below.

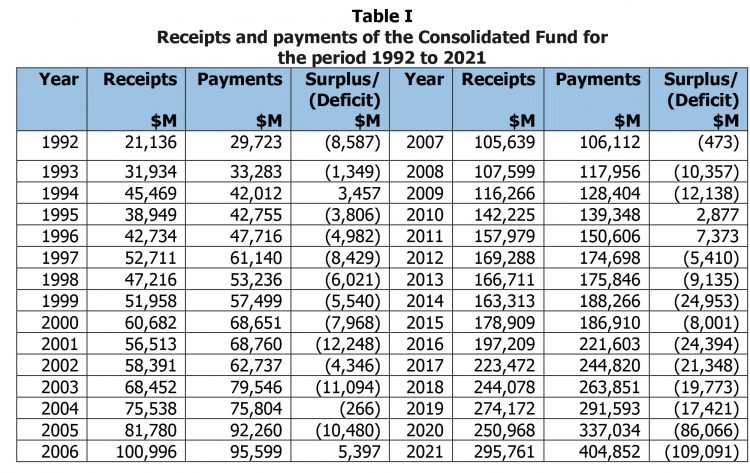

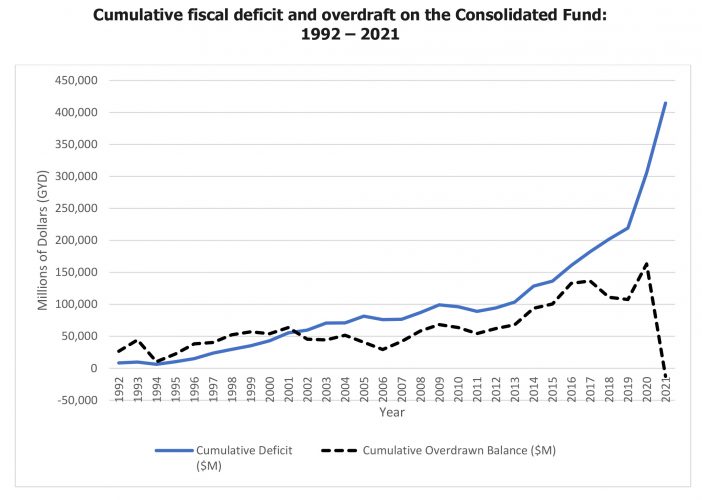

The overdraft on the Consolidated Fund had been building up over the years mainly as a result of the incurrence of fiscal deficits. Table I shows the receipts and payments of the Consolidated Fund from 1992 to 2021 as well as the fiscal deficit for those years, as extracted from the reports of the Auditor General. The 2022 report is not yet available.

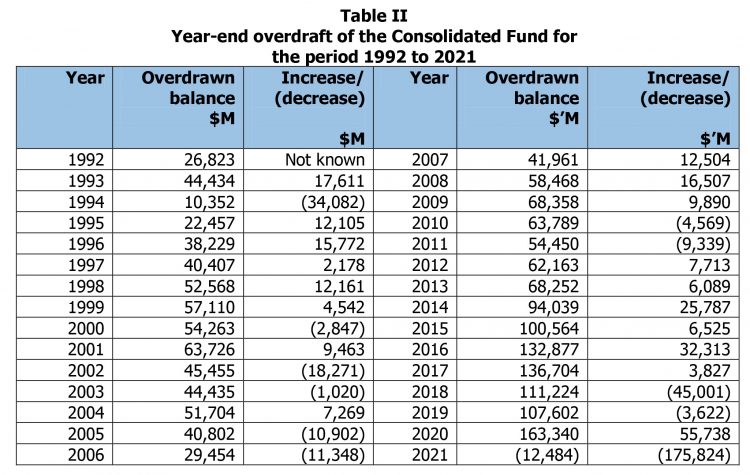

In relation to the overdraft on the Consolidated Fund, at the end of 1992 the figure was $26.823 billion. By 2013, the overdraft increased to $68.252 billion, giving an average annual increase of $1.973 billion over the 21-year period. However, during period from 2014 to June 2021, the overdraft increased significantly from $34.859 billion to $103.111 billion, giving an average annual increase of $4.648 billion, as shown at Table II:

The increase of $$55.738 billion in the overdraft in 2020 from $107.602 billion to $163.340 billion was again due mainly increased expenditure in infrastructure development works. However, in that year, in excess of 17,000 cheques valued at $49.037 billion were drawn close to year-end and well into the new year in order to exhaust budgetary allocations. This is a violation of the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act that requires all unspent balances to be surrendered to the Consolidated Fund. Similar observations were made in previous years.