We will pay some attention to this both diachronically and synchronically and rediscover the vast, deep and amazing work done by Amerindian artists, and that done by others who have engaged the Amerindian aesthetic in one way or another. In the twenty-first century it is a fascinating discovery and a profound abstract and modernist development in the national art. It has been an outstanding new area in form and focus.

Ironically, this heritage that gave rise to what is among the newest discoveries in Guyanese art is also responsible for the oldest. The first forms that may be included in the category of art are almost as old as human existence itself in the Guianas. It may be said that Amerindian art began with the petroglyphs – carvings, etchings, writing, drawings on the surfaces of rocks done by Guyana’s indigenous populations who first inhabited the territory some 7,000 years ago (see Denis Williams). The pictograms themselves have been dated back to a period 3,000 – 5,000 years ago.

These petroglyphs are also known as “timehri” and Williams has described one type of rock carvings/ drawings /paintings as timehri, while another is the Aishalton type. The village of Aishalton in the Rupununi savannahs of Southern Guyana is the best known site of these pictorals in the country, an area mostly inhabited by the Wapishana people. According to the theory of ritual origins such visual utterances originated in spiritual or religious beliefs among pre-historic groups trying to survive, to come to terms with and to influence their well-being in a hostile environment that they did not understand. They intended to gain some control by communicating with spirits or deities; but these are also believed to tell stories crucial to the lives and existence of the race.

There is unknown depth in these survivals of pre-historic art, if we may thus term them. They represent the pre-Columbian epoch, but the art that came after, that was practiced in the long Colonial Era lacked that kind of depth and were, in contrast, fairly superficial and descriptive as far as a people’s art is concerned. They did have, however, two vital functions. What has survived as Amerindian art from that period is dominated by the work of artists who came to the colony of British Guiana in the service of visiting explorers, geographers, botanists and anthropologists. These scientists employed the artists as illustrators to sketch and provide documented records of what they discovered in the field. This partnership produced a priceless collection of drawings and paintings of Amerindian village life in interior locations – pictures of people and places that were invaluable to the anthropologists but also created a corpus of work that documented a kind of art being done in the colony in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.,

This art shows what Amerindian life looked like as well as remain to demonstrate a type of art. The pictures transcended the illustrative and the anthropological to claim a place as art works in their own right. An outstanding case is that of English artist Edward Goodall who accompanied Robert Schomburgk to British Guiana and fell into dispute with Schomburgk over ownership and identity of his art. An important collection of Goodall’s pieces is published in Sketches of Amerindian Tribes 1841 – 1843 edited by Mary Noel Menezes (1977).

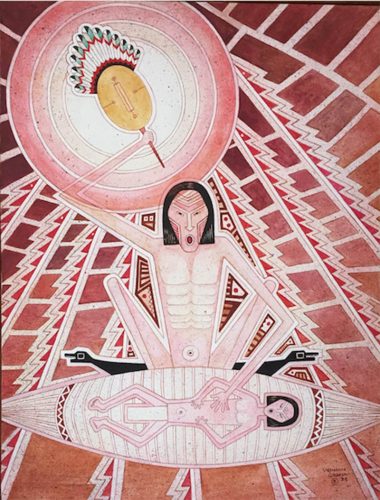

For a very long time Guyanese Amerindian art largely engaged them as subjects – pictures of the people, their activities and their environment. This continued well into the twentieth century. Two outstanding artists considerably changed this landscape in Guyanese pre-independence art. One was the foremost painter Aubrey Williams, whose interest in Amerindian subjects assumed great intellectual depth in a much more meaningful engagement. Williams’ was a study of the ethos that began with exploration of the petroglyphs and the motifs using symbols and images. It was still art by non-Amerindians and ‘outsiders’, but among the greatest differences between this art and what preceded it was in the first place it was work by a Guyanese, but more than that, it was abstract art and the beginning of modernist work in this category of the art.

Williams received training and went to work as a civil servant in the field of agriculture, which took him to outlying areas of the country. According to Kobena Mercer he spent a few years stationed in Hosororo where he was in contact with the Warrau nation. This experience obviously afforded him much study and interest in the culture and influenced the art that he began to produce soon after going to England in 1952 and becoming a professional artist. He exhibited a number of abstract paintings revealing this influence, including a 1959 exhibition in London and the important painting “Roraima” (1963). Williams painted several pieces in his Timehri suite of public murals that adorned the Timehri Airport (now the Cheddi Jagan International Airport).

The other major artist to have changed the landscape was Marjorie Broodhagen, the foremost female artist at that time, who for many years after advanced Amerindian art in Guyana. Another important difference between Broodhagen and what preceded her was that she was partly of Amerindian descent, so that the people were moving from subject to artists producing Amerindian art. This was a prominent factor by the time ceramist and painter Stephanie Correia came to prominence. She made a major impact and rendered Amerindian art especially visible through her use of petroglyphs, motifs and symbols displaying the people’s ethos in ceramic works. Soon after her paintings deepened this preoccupation as she studied and engaged mythology to add another dimension to the march forward of Amerindian art in Guyana. Her work is still continued in the same vein by her daughter Anna Correia, also an artist, who has studied and promoted her mother’s work, including presentations in public lectures.

By the 1980s Amerindian art was much richer because of the emergence of Amerindian artists as well as abstract work and work reflecting the culture. That was to deepen and become much more celebrated by 1990 with the development of painter George Simon and his brother Oswald Hussein. Simon had been steadily rising with his large canvases studying traditional life such as hunting and fishing before he grew more complex and considerably more profound. Hussein rose swiftly to prominence after winning the Guyana Visual Arts Competition and Exhibition in 1989 with sculpture that was earth-shaking, exceptional and new. He revealed a number of the characteristics that today make Amerindian art in Guyana unique and striking. These include elements of the Amerindian cosmic consciousness, the ethos and spiritual beliefs. Animism was always a part of the mythology and since the 1980s it emerged as a strong vein in their art. It was an outstanding spiritual factor in the sculpture of Hussein, who broke new ground with a study of these factors in his art.

The nation was given very clear notice that Amerindian art as a powerful factor in Guyanese art had arrived in 1996 with the exhibition held in the Venezuelan Cultural Centre entitled “Six Lokono Artists”. This was the first exhibition of its kind, and the first public showing of the work of most of the men involved. They were all students of Simon who had been guided by him in St Cuthbert’s Mission, and included Hussein and fellow sculptors the Klenkian brothers and Telford Taylor, also a sculptor. The leader Simon, as a painter, joined his students in the exhibition.

Linus Klenkian and Taylor were the two to have continued in an upward path since the exhibition to make a mark in national art alongside the two most prominent Simon and Hussein. The name “Lokono” signaled their ethnicity, since it is the Arawak word that describe their race and their Amerindian nation; it is the name, whose adjectival form is “Loko”, that is known to speakers of English as Arawak. It was used in the exhibition not only to identify the artists as Arawaks, but to signify the style, nature and preoccupations of their art.

Apart from Simon, who distinguished himself after 2000 in mythology, shamanism, and post-modernism, another Amerindian artist whose work has developed along a very different and personal trajectory that nevertheless still exhibits characteristics that typify Amerindian art, is the sculptor Winslow Craig, who is not a Lokono. Both of these, who rose to the very top of Guyanese art, need further description to capture the essence of their work, their originality, identity and artistic directions.

It will require another session of description and analysis to pinpoint the development and major features of their work as individuals to add to some of the characteristics of Linus Klenkian and the qualities such as the mythology, the strange reflections of Kanaima, the rainforest, the landscape, the animals, the wood used for carving and the spirituality that go together to make contemporary Amerindian art.