By Miranda La Rose

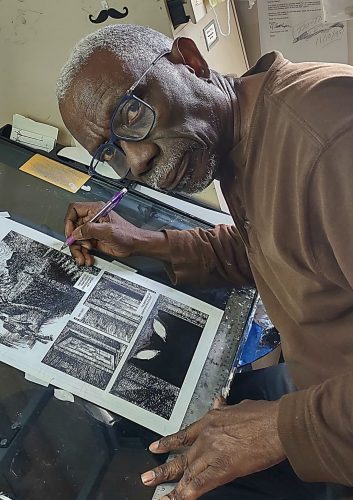

Harold Bascom, self-taught in every sphere of his professional life, is an award-winning playwright, artist/illustrator, stage director and author. Formerly, Bascom was a public service employee who also taught in the secondary and, partially, in the tertiary education systems based solely on the skills and experiences he accumulated over time.

“Somehow my method of learning has rubbed academics the wrong way. I find I have been resented, sidelined and obscured by my fellow Guyanese because they say, ‘Bascom should not be among us because he has no degree’, but I’m okay with that,” Bascom told Stabroek Weekend from his home in Georgia, USA.

The late educator Samuel Small, he said, once asked him to teach creative writing on the University of Guyana’s Distance and Continuing Education programme after reading his first novel, Apata.

“He was amazed at my method of teaching people how to write creatively. The class was going very well until one day, Mr Small told me the university’s people said I had no university degree and as such I could not teach under UG’s name,” he recalled.

On another occasion, he said, his then wife, who was a student in the sociology class at UG said one of her lecturers wanted him to speak at the university on the subject of mediocrity in Guyana as he saw it.

“I delivered the lecture but subsequently there were grumbles about who had the temerity to bring this man without a degree to the university. I have six subjects at College of Preceptors to my name but I have this ability to pick up books or manuals, read, practice and learn,” he said.

Another day he was introduced to a University of the West Indies professor who told Bascom he was a “mere storyteller. Well, I’m happy creating and I know I’m good at what I do. Creatively, I’m like the shark. The shark has to continue swimming lest he sinks to the bottom. I have to continue creating, if I don’t, I don’t know what will happen to me.”

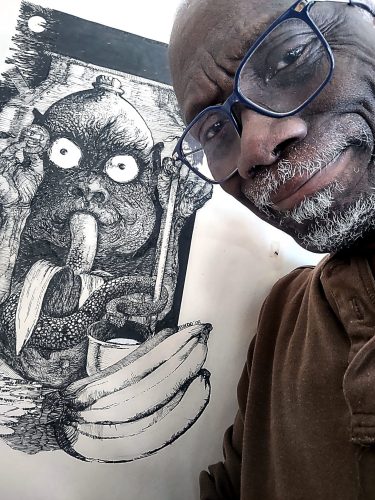

He recently composed a series of graphics of Guya-nese mythological figures, ole higue, jumbie, moongazer, bacoo, kanaima and water people. “People are using those images without giving me credit,” he noted.

Now 72 years old, along with Apata, Bascom has written 19 full-length plays, a self-published book of 101 words that tells you are a Guyanese, a Guyana colouring book and several other unpublished works. He also plays the trumpet and the flute, having taught himself.

He is a four-time winner of the Guyana Prize for Litera-ture in the drama category.

“My first play, Two Wrongs, won the Guyana Prize in 2004. That story, influenced by my brother George and his best friend Kumar Jagdeo who were inseparable growing up and who in the story died together under the vicious blow of racism, was based on the 1962 race riots.”

Jagdeo migrated to Canada.

Bascom won the Guyana Prize again for Makantali in 2006, and in 2010 for a radio documentary drama called Blank Document. In 2014, he yet again took the top prize for the play, Desperate for Relevance.

Nomadic

Bascom was born in Vergenoegen, East Bank Essequibo but his family moved a few years later to Best Village, West Coast Demerara, then New Road, Vreed-en-Hoop, a cross-cultural community that influenced his first novel and for which he still gets nostalgic. “Even though we were Black kids, we used salutations like ‘What happening deh Babu? It never dawned on me until I left New Road that a lot of my language, intonations were actually inter-mixed with East Indian lingo,” he recalled.

A writer friend who looked at Apata’s manuscript had expressed concern about Bascom’s use of the word ‘bhai’ many times, noting its East Indian origin.

While living in New Road, Vreed-en-Hoop, Basdcom’s father sold women’s clothing from a grip (suitcase) in Linden. After a while the family joined him in Linden for a short period.

In Linden, Bascom attended Christianburg Wismar Multilateral School. He was still there when the family returned to New Road. Then his mother returned to Linden and he went to live with his uncle in Middle Road, Pouderoyen.

“As a young man, I went back to Linden. Then my brother Wilbert found me a job at Designs and Graphics in Georgetown after which I got married and lived in Georgetown. I subsequently worked at the old Chronicle then at the Ministry of Education before going back to Linden to teach. I was quite nomadic,” he recalled.

Bascom was twice married. Both wives died and he now lives with a partner.

The Bascoms

The Bascoms are a creative family in drawing and painting, Bascom said. His father, a joiner, with no regular schooling, was gifted in sketching. His brother Wilbert, once the general manager of the Guyana National Cooperative Bank, was an artist. The brother before Bascom was also an artist.

“I found that I could draw. In my preteens, I told myself I wanted to be like the American painter and illustrator Norman Rockwell,” he recalled.

Bascom had his primary education at St Swithin’s Anglican School, Malgre Tout Government School on the West Bank Demerara and after passing the CP examinations he went to West Demerara Secondary and Christianburg Wismar Secondary Multilateral schools.

He did not complete his secondary education and began working at the Demerara Tobacco Company Limited (Demtoco) as a sign artist, which was not what he wanted to be.

“I decided I wanted to illustrate books and produce cartoons,” he said. He prepared a portfolio, took it to the Demtoco public relations office and to the Chronicle newspaper then located next to Bookers (Guyana Stores) Ltd. At Chronicle he met the art director, Eddie Hooper (Guyanese singer).

“I worked with him as his assistant. I was 19 years old when the Mighty Sparrow came to Guyana and he wanted Eddie to help him arrange his music. That was how I became the art director in 1970 at Chronicle at 19 years old,” he recalled.

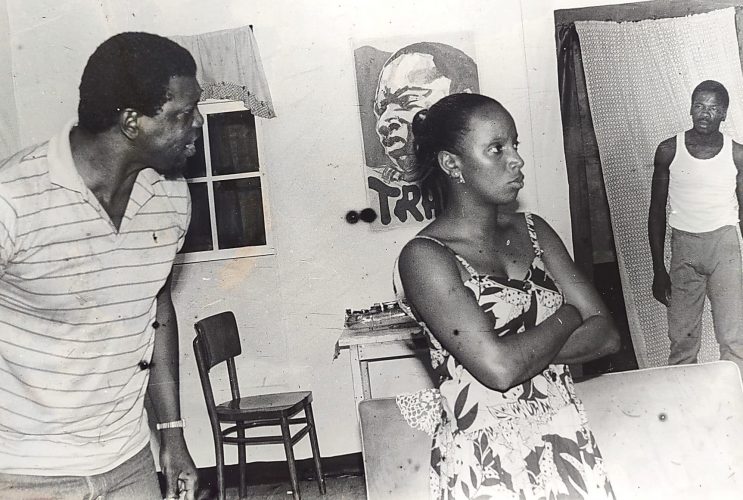

While he was there, African-American illustrator Tom Feelings visited Guyana to teach a core group that included Bascom how to design and illustrate books.

“In 1973, I left the Chronicle and became an illustrator with the Ministry of Education. After Feelings left I became the chief illustrator in the ministry. We created the books, ‘Our First Village’, ‘The Moco-Moco Tree’, ‘The Cumfa Drums are Calling’ and a series called ‘We Came From India’, ‘We came from China’ etc,” he stated.

Bascom worked between the ministry and the Guyana National Service publishing centre in West Ruimveldt.

“I had my department of civilian illustrators while the GNS had theirs. A conflict arose between me and the person in charge of the publishing centre. As a public servant I had to return to the ministry. I was drawing money without doing any work so I started writing articles for the Chronicle. I then suggested to the ministry that I teach graphic arts in Linden. I developed my own syllabus and taught at Christianburg Wismar Multilateral School between 1983 and 1985,” he explained.

After that, he returned to Georgetown and worked with the National Centre for Educational Resource Development in Queen’s College compound. He subsequently left the ministry to focus on producing plays and directing them at the National Cultural Centre (NCC).

During that time, he also taught graphic arts at the Burrowes School of Art.

“Everything I taught was basically self-taught except for what Tom Feelings passed on to me. I read a lot of books and researched a lot,” he noted.

Playwright

His first play at the NCC was ‘The Barrel’. “I can say, I revolutionised theatre in Guyana. It brought the masses out to the cultural centre. Most of what I’ve done in writing and in the arts and what I continue to do was because I wanted to become a film director. It still continues to be my dream,” he said.

Noting that he had seen stories in books set to the screen, he thought he should write a novel about Guyana, turn it into a film which he would direct. That was the origin of Apata.

As an eight-year-old, he remembered the excitement that the manhunt, led by Sir David Rose, in Parika Backdam for the criminal Clement Cuffy brought about. He watched from New Road as police cars made their way to Parika and heard the adults talking about Cuffy’s escapades.

“As a young man I thought I should write a novel about Clement Cuffy,” he said.

Bascom started to research articles about Cuffy at the National Archives and then archivist Tommy Payne, he said, asked him why he was wasting time doing research on a criminal.

“On a parallel level the Americans were writing stories about John Delinger and Baby Face Nelson and others and making money. I said, ‘Man, I’m writing this novel’. True to form, I started writing, researching and reading other novels to get ideas. I started in 1983,” he recalled.

Before Apata was published, Bascom said, there were many detractors. People told him he had to be out of the country to publish his book. He wrote letters to different publishers asking if he could submit a manuscript from Guyana because he was not living in England.

“The response was ‘Why not?’ I sent my manuscript for Apata, the story of a reluctant criminal, to Heinemann Educational Books, London. It was published in 1986. With that I said my chance of making a movie is here but the reality of making it into a movie was a different thing. Nothing came out of Apata as a movie,” he said.

He recalled Allan Fenty reading short stories on the radio. He wrote one and sent it to the then Guyana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC). “They wrote telling me the story was too short. I went to the National Library, borrowed a few books on how to write short stories and I wrote another short story. I sent it back to GBC and it was a hit,” he reminisced.

Bascom then turned to writing and directing plays hoping he could later turn one into a film.

While teaching at Christianburg Wismar Multilateral School he wrote his first small play called Quadruped, a story about a four-footed animal, involving a cast of first formers. “It was a hit in the school’s auditorium,” he said.

Quadruped inspired him to aim for something bigger. “During the 1980 economic crisis when you had to join the oil line, the rice line, the butter line and other lines for basic commodities, I wrote a play called The Butter Line. When I staged that play at the Lichas Hall in Linden, it was sold out. I saw audiences who were excited to see their own Guyanese cast live on stage in a respectable way. Prior to that, the only time you saw a local character was in the kitchen or the backyard while the main characters were middle class, upper class people speaking the Queen’s English,” he recalled.

He took inspiration for The Butter Line from a collection of plays by Russian playwright, Maxim Gorky, whose plays, set in the Russian Revolution, were about the Russian peasants and their regular life. “I said, if Gorky can write a play about his regular people, why can’t I?” he recalled.

When a housewife from Canvas City, Linden congratulated him on The Butter Line, it made him realise that he needed “to write plays, sketch paintings, create music about our lives and based on common experiences.”

When Bascom returned to Georgetown in 1985, he wrote and staged the play, The Barrel, based on the economic situation at the time.

After The Barrel’s success he left teaching to focus on writing plays full time.

“My last play, Cockle House, after which I came to the US, I took to New Amsterdam and Linden because I was dealing with this plague of elderly men with money sexually ravaging young women and I wanted to expose it in my play. In the play, when the s..t hit the fan, they went to the homes of the young women and paid off the parents. Cockle House ended with the daughter of the man who assaulted young women, offering a mother a certain amount of money and the mother refused to accept it as the offer got higher and higher,” he explained.

Bascom calls his plays, ‘mirror plays’ because they reflect society. “I want Guyanese to see themselves. If they see the negative, my hope is that they correct it. If they see the positive my hope is they enhance it and continue with it. It is the same thing with my art,” he added.

Bascom held his first exhibition of paintings in 1993 at the then Park Hotel on Main Street. “It was an exhibition of nudes depicting the tough things Guyana was experiencing economically,” he recalled.

He migrated to the US in 1996.

His first 171-page graphic novel, Stray, inspired by a Guyanese jumbie story, is set in a fictional city in Georgia.

“When I was small,” he said, “I heard the story of a woman who was coming home one night, and picked up a baby crying at the roadside. As she gets closer to her home the baby gets heavier. When she reaches her gate the baby transforms into a jumbie who demands, ‘Take me back whey you get me.’”

He took that story and turned the baby into a pet that becomes a vampire and is picked up by unsuspecting victims.

“If foreign writers can take our folklore and make creative property out of them, why shouldn’t we use our own folklore and make international properties out of them?” he asked rhetorically.

Bascom works closely with local writer Michael Jordan and Guyana 2022 prize winner for poetry Berkley Semple. No writer works without a developmental editor. “Berkeley and Jordan understand that,” he said. The three act as developmental editors for each other.

“The developmental editor does not tell you what to write. He tells you if what you write makes sense. That is how we get the best out of our work,” he adds.

At one time, Bascom said, some people claimed that only writers who lived outside of Guyana could win the Guyana prize because of access to publishing. “It is harder to get stuff published in the established press here because it is based on business and not politics,” he said.

In his spare time, Bascom writes snippets about local writers and artists on Facebook titled ‘Lest we forget’. “As a country we have done horribly in terms of documenting our past creatives. There is a dearth of information on local writers and creatives on the whole,” he lamented.