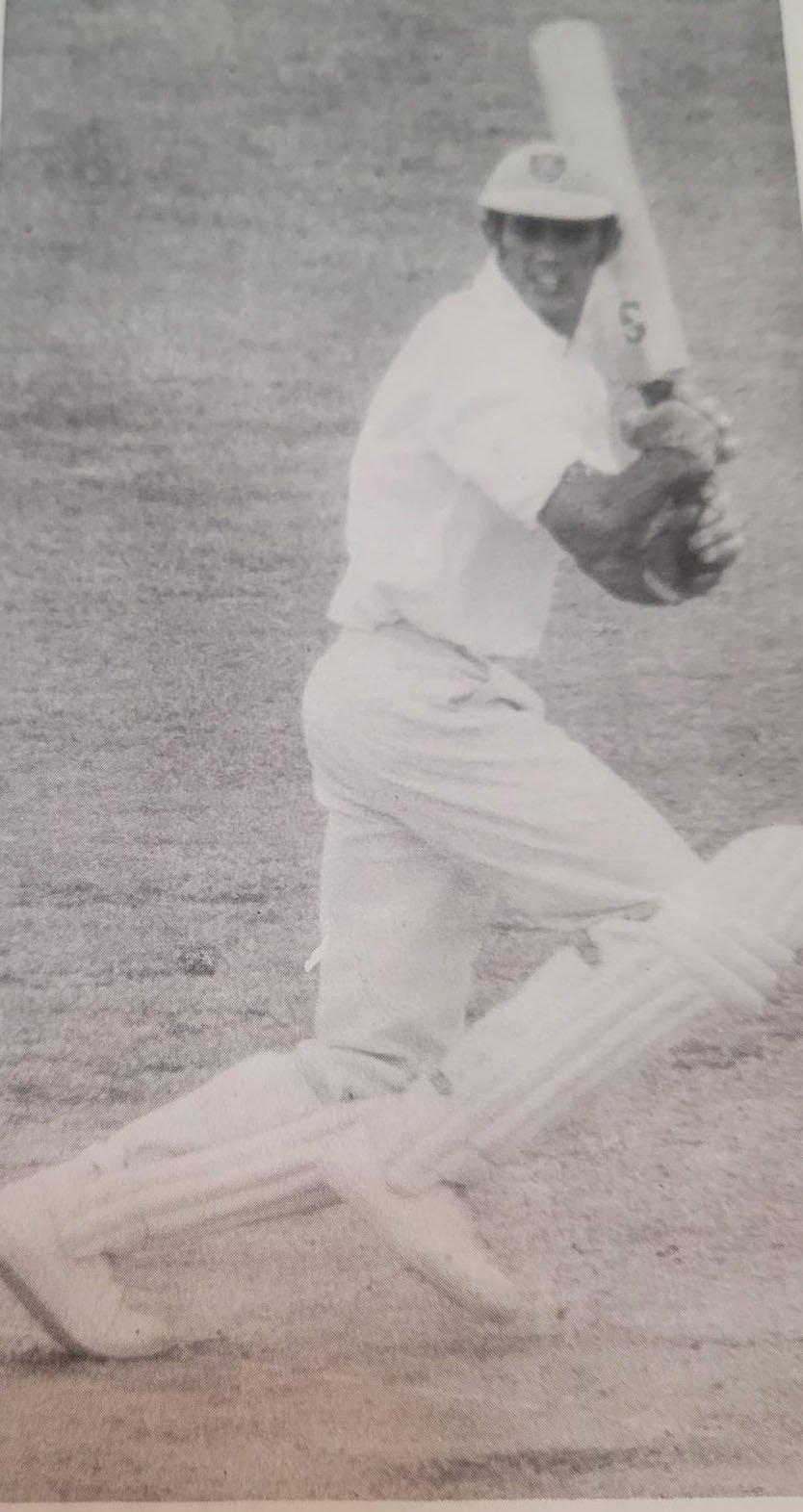

In this week’s edition of In Search of West Indies Cricket Roger Seymour looks at the oft overlooked Test career of Charlie Davis, the Trinidadian Boy Wonder.

Recently, I stumbled on my notes from the Charlie Davis interview. I can’t recall exactly how I got in touch with him, but he readily agreed to chat and we arranged to meet in the Food Court at Long Circular Mall, St James, a suburb of Port-of-Spain, at 10 am, on Tuesday, 11th March, 1997. Davis, affable and gracious, revealed a sharp memory of his cricketing days.

“I was about 15 years old when I decided I was going to play for the West Indies,” Davis said. A prolific run scorer as a schoolboy, he seemed destined to wear the Maroon colours. Davis came from a sporting family in the suburb of Belmont. His mother, Kathleen (nee Lambie) represented Trinidad in hockey, while his father, Charles Allan, was a keen all-round sports fan. His sister Alana also represented Trinidad in hockey in the 1970s. Charlie and his brother Bryan spent countless hours playing cricket in their yard. Four years senior, Bryan batted most of the time whilst his younger sibling bowled.

At the age of 12, Davis was on the Belmont Intermediate School team, and a year later, he entered St Mary’s College, where Bryan, captain of the College’s First XI, had already made a name for himself. Davis made rapid progress under the watchful eye of the college’s coach, Kelvin ‘Pa’ Aleong, and formed a firm kinship with his sons, Eddie and Andy. When two players failed to appear for a match, Andy and Charlie found themselves in the school’s Intermediate XI. In 1959, at the age of 15, Davis was selected for the annual match against arch rivals, Queen’s Royal College, captained that year by future West Indies wicketkeeper, Deryck Murray. In the following season, Davis scored a century against rival Fatima College, and five half-centuries in other matches.

In 1961, Davis grabbed newspaper headlines, becoming a household name in Trinidad. He compiled a double century against San Juan United, whose attack included Charran Singh, the left-arm, orthodox spinner, who had represented the West Indies in two Test matches versus England in the previous year. He won his first cap for Trinidad against E W Swanton’s XI – a touring team of Test and English County cricketers – at the Queen’s Park Oval, April, 7, 8, 10, & 11. It was a bittersweet first class debut for Davis, as the hosts surpassed the visitors’ first innings total of 302 by 29 runs, with the Davis brothers leading the way. Bryan, opening the batting, scored 68, while Charlie chipped in with 58, and Joey Carew, 53. However, Trinidad collapsed in the second innings for 164 runs and lost by 88 runs. Bryan, 74, Willie Rodriguez, 40, and Charlie, 11, were the only batsmen to reach double figures. In the annual Beaumont Cup match, North Trinidad versus South Trinidad, his second First Class appearance, Davis scored 115, for the former, followed by another hundred for Trinidad B versus Tobago.

In the 1961 Quadrangular Tournament held in October in British Guiana, Davis’s appetite for runs continued on his inter-territorial debut at Rose Hall, Berbice. Replying to British Guiana’s mammoth total of 501 (Joe Solomon, 166, Glendon Gibbs, 129), Trinidad were in deep trouble at 17 for four, when Davis, batting sixth, arrived at the wicket. Standing head and shoulders above his more experienced teammates, the 17-year-old led the rear guard action against an attack spearheaded by Test off-spinner Lance Gibbs and fast bowler Charlie Stayers. At 81 for seven, Davis found an unlikely ally in Charran Singh, 80, as he shepherded the tail, and guided Trinidad to a score of 257. His innings of 127 reflected his temperament to deal with pressure. Following on, the visitors compiled 414 for seven declared, with both Davis brothers falling to Gibbs with their scores on 97. British Guiana knocked off the 171 runs required for the victory, but the teenager had arrived on the Caribbean stage.

Shortly afterwards the headlines of the Trinidad newspapers screamed, “Charlie Davis called for WI 23”. The West Indies selectors had included the Boy Wonder in the squad to prepare for the 1962 India Tour of the Caribbean. Davis dismissed any thought of selection. The West Indies’ 1961 side – just back from the 1960/61 Tour of Australia – was a unit on the ascent, and the middle order was filled with illustrious names: Rohan Kanhai, Seymour Nurse, Basil Butcher, Frank Worrell, Garfield Sobers, Joe Solomon. “I thought it was irrelevant, I knew I had no chance of getting picked,” Davis told Veersen Bhoolai in a January 1996 interview. Davis, unaware of how good his chances were, had lacklustre scores of 20-odd and 30-odd, playing for Trinidad Colts and Trinidad, respectively, in India’s first two matches on the tour, both at the Queen’s Park Oval. Later, Sobers inform-ed him that if he had made just 50, he would have been selected as Worrell was looking to see that he was in good nick.

Back at St Mary’s, Davis was appointed captain of the college’s First XI, a post he held until leaving the school in 1963. In his final year, the dependable right hand batsman scored seven centuries in eight matches in the Trinidad Cricket Council’s North Zone Senior Grade Competition. The only team spared was the Queen’s Park Cricket Club, which he later joined. An offer from Gloucestershire County Cricket Club to the Davis brothers did not appeal to him, since it meant abandoning any hope of playing Test cricket, and a long period of residential qualification. (In 1968, when the registration rules were changed to allow counties to sign one overseas player without any residency stipulation Bryan spent two seasons with Glamorgan in 1969 and 1970. In his initial season Glamorgan won the County Championship and finished in the runner-up position the following year, with Bryan surpassing 1,000 runs in both two campaigns.)

As the West Indies rose to the summit of the cricketing world, there was still no place for Davis, despite scoring heavily in territorial matches and Trinidad club cricket. By this time, the Davis boys were fixtures in the Trinidad XI (his sibling, Bryan, was a solid opening batsman) . When Australia visited the West Indies in 1965, there was no settled opening partner for the prolific Conrad Hunte, and Seymour Nurse was pushed up the order to open in the First Test, which the hosts won by 179 runs. In the drawn Trinidad v Australia territorial match, Charlie had scores of 71, and 51, while Bryan notched 26, and 30. Bryan was then chosen as Hunte’s partner for the rest of the series, enjoying knocks of 54 and 58 on debut, whilst sharing opening stands of 116 and 91. His only other score of note was in the second innings of the Fourth Test at Kensington Oval, Barbados. With the visitors trailing 2-0, Australian Captain Bobby Simpson, desperate to try and salvage the series, declared his team’s second innings; thus tempting the West Indies to chase 253 for victory in four and a half hours. Although Hunte, 81, and Davis, 68, rattled off 145 in 170 minutes, a new West Indian record for the first wicket versus Australia, the West Indies, with five wickets intact, were 11 runs short of the target when time expired. Although Bryan was selected for the 1966/67 Tour of India and Ceylon, he didn’t play in any of the Tests, and his brief Test career was over.

A new middle-order star, born the same year as Davis, the Guyanese left-hander, Clive Lloyd, emerged on that Asian Subcontinent tour. The next opportunity for Davis to show his mettle to the selectors arose when the President’s XI faced the MCC in their initial First Class match of the 1967/68 Tour of the Caribbean on 3rd – 6th January, at Kensington Oval. The first six batsmen in the batting order were all jostling for places on the West Indies team: Steve Camacho, Geoffrey Greenidge, Roy Fredericks, Maurice Foster, Charlie Davis and Richard de Souza. After Camacho’s 85 (run out) had propelled the home side to a solid start, Davis stole the show. Former England Captain Brian Close, who covered the series as a journalist, described Davis’ innings thus: “The enterprising Davis swiftly put a damper on the note of enthusiasm appearing among the MCC players who had seen the President’s team slide from 163 for two to 169 for four. Davis, finding a dour partner in De Souza, put in some useful propaganda work on his own behalf with 60 untroubled, neatly stroked runs before the close.

“He played with such confidence and freedom that his century [158] looked inevitable and it came on the second day as the President’s XI took their score to 435 [for nine] before declaring.”

Three days later at the Queen’s Park Oval, Davis took 68 off the MCC attack on the first day of the drawn four-day encounter with Trinidad, and followed it with another half-century, 62, in the second innings. An undefeated century, and two fifties, but still, no place for Davis in the West Indies XI. (Camacho played all five Tests as an opening batsman).

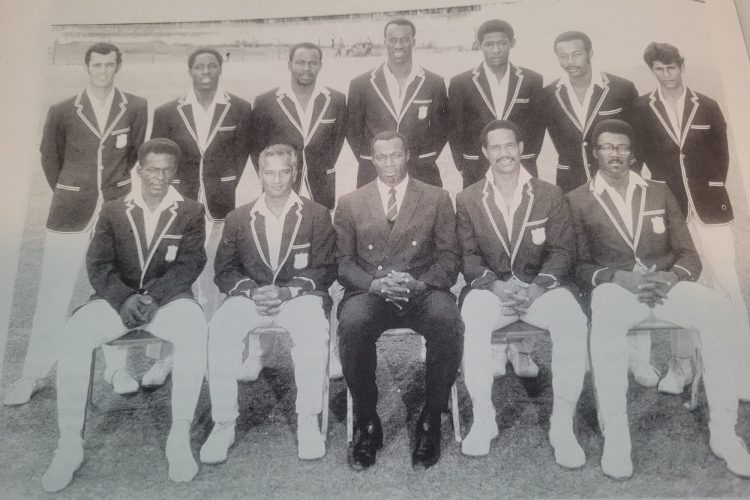

On 31st March, 1968, the rest day of the Fifth Test match between England and the West Indies in Georgetown, the selection panel comprising Chairman Berkeley Gaskin, Everton Weekes, Esmond Kentish, F L Thomas, Jeffrey Stollmeyer (in place of the unavailable Gerry Gomez) and Captain Garry Sobers met to select the team for the 1968/69 Tour of Australia and New Zealand. The chosen few were announced on 4th April, the day after the Test was drawn, and England had won the series. There were four new names in the tour party; Charles Allan Davis, Richard Edwards, Mike Findlay and Roy Fredericks.

It was a disappointing trip for Davis as he experienced failure for the first time. For the Second Test at Melbourne, fast bowler Charlie Griffith, Lloyd (injured) and all-rounder David Holford were replaced by debutants Edwards, Fredericks and Davis, respectively. Davis was selected for his bowling after taking seven wickets for 106 in the drawn match versus South Australia, three days prior, and was slotted in at number eight in the first innings. Arriving at the wicket with the West Indies in dire straits at 170 for six, Davis joined his roommate, opening batsman Fredericks, who had batted through the entire first day of that Boxing Day Test, albeit shortened by rain. When Fredericks departed seven runs later, Davis held firm for 79 minutes, garnering 18 runs before succumbing, as the seventh of eight victims for the Australian speedster Graham McKenzie. In the second innings, batting ninth, Davis stuck around for 50 minutes as the West Indies lost by an innings and 30 runs.

It was the only Test of the eight on the tour that Davis played, as Lloyd returned for the Third Test. In 11 first class matches, Davis compiled 323 runs, with a solitary 50 in 20 innings, for a paltry average of 16.15. Two memories linger with Davis from that trip. He had roomed with Fredericks, and for the rest of his Test career he steadfastly refused to share accommodation with anyone else, as the two developed a firm friendship. Also, he adopted his ‘run out is not an out’ philosophy. In the Australian series, Davis was twelfth man in the other four Test matches, and was on the field for most of the matches, as “Rohan Kanhai did not like to field” and was always complaining of some injury. (Kanhai did not play in any Tests in New Zealand and missed the subsequent 1969 Tour of England with a knee cartilage injury). Towards the end of the tour, Davis said, he addressed his teammates in the dressing room: “Gentlemen I have paid my dues. I have fielded too many balls, therefore when I go out to bat, you’ll have to get me out with a chisel. From now on I don’t consider run out, to be out. So any time there’s a mix up at the wicket, it’s someone else who will be out, not me. Run out is not out. You run yourself out.”

On 20th April, 1969, less than a month after their return from the arduous five month Australasia trip, the West Indies team departed from Barbados for a three-Test series in England. Davis figured he was selected because his bowling might be an asset, although he thought it was affecting his batting. In fact, it was further dismantling of the great 1960s team. Only five players returned from the successful 1966 tour. Nurse had announced his retirement from Test cricket during the trip Down Under, Griffith and Hall had played their last Tests in New Zealand, and Kanhai was injured. There were six more new faces: Phil Blair, Maurice Foster, Vanburn Holder, Pascal Roberts, John Shepherd and Grayson Shillingford. The West Indies were in transition.

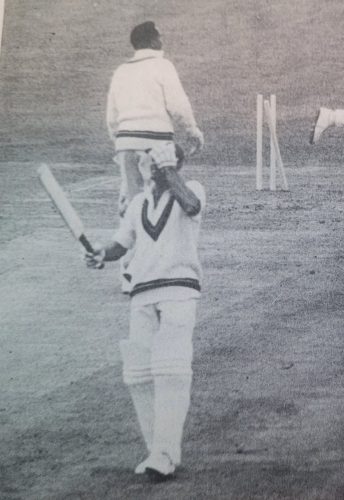

The English tour was another disaster, with the West Indies losing 2-0. In the First Test at Old Trafford, Davis, batting fourth, top scored in the first innings collapse with 34, as the West Indies, 147 all out, were forced to follow on, and eventually lost by ten wickets. In the Second Test at Lord’s, Davis batting at three, went to the middle after Fredericks, 63, and Camacho, 67, had given the West Indies their best ever opening stand in England; their 106 surpassing the 103 established by Rae and Stollmeyer at Trent Bridge in 1950. With Davis holding the fort at one end, and Sobers, 29, beginning to open up, the visitors were cruising along at 217 for three, when there was a terrible mix up and Sobers was run out. Davis, the non-striker, called for the run, Sobers said no, Davis turned back, only to be surprised to hear Sobers running towards his end. Too late, Boycott fielded the ball, sprinted in and broke the wicket.

Mortified at having run out his idol, Davis decided, “the safest thing I could do was to stay out there and to bat for as long as possible.” His innings of 103 – the only Test century scored by the West Indies on that tour – lasted for 371 minutes and was the centrepiece of the first innings total of 380. He recalled, “I didn’t know it at the time, but Sobers is not one to bear grudges. When I returned to the pavilion, he was the first person to greet me and offer congratulations.” The match finished in a draw with both sides pressing for victory; England 38 short of the target, as the West Indies fought to capture the last three wickets.

The West Indies lost the Third Test at Leeds by 30 runs, as they chased 303 on the final day. Davis, coming in at the early dismissal of Fredericks, batted attractively whilst adding 61 with Camacho, before he was given out to a controversial decision, caught and bowled by Derek Underwood for 29. Butcher, 91, appeared to be leading the West Indies to a convincing victory when he was also ruled out – caught at the wicket – in contentious circumstances. In 16 first class matches, Davis scored 848 runs at an average of 42.40, with two centuries, and finished fifth in the averages and fourth in the aggregates.

As India’s 1971 visit to the West Indies approached, Davis didn’t have much hope of retaining his Test place. Kanhai had been recalled at the eleventh hour and there was a clarion call for the inclusion of two dynamic young players, Lawrence Rowe and Alvin Kallicharran. Married in July 1970, Davis’s wife was expecting their first child and he decided to concentrate on his business career. A sales representative for the West Indian Tobacco Company, he attended a business course on the Isle of Wight in late January. His return to Trinidad coincided with the territorial game versus India at Guaracara Park, Pointe-a-Pierre. Davis compiled an even century and was selected for the Second Test two days later at Queen’s Park Oval. As the mysterious and feared Indian spin quartet of Bishen Singh Bedi, Erapalli Prasanna, Salim Durani and Venkataraghavan spun circles around the befuddled West Indies line up on the spin-favoured Trinidad wicket, Davis was completely at home. In the Second Test loss, Davis was undefeated in both innings with scores of 71 and 74. In the drawn Third Test at Bourda, Davis scored 34, and 125 not out, sharing an unbroken fourth wicket stand of 170 with Sobers, 108. In Bridgetown, Davis enjoyed innings of 79 – while adding 167 for the fourth wicket with Sobers, 178* – and 22 not out. In the final Test, at Queen’s Park Oval, Davis, 125, and Sobers, 132, once again tormented the Indian spinners whilst adding 177 for the fifth wicket, in the first innings. His second innings score of 19 was crucial for the time it occupied, as the hosts batted through the final 20 overs to save the match. Davis topped the series averages with 132.25 whilst compiling 529 runs in eight innings.

Davis attributes his success against the Indian quartet to the way he was taught by Aleong, who “didn’t believe a spinner should get anybody out.” He was instructed to play a good ball on merit and bad balls where to be dispatched to the boundary. “I think they were shocked because I was the first West Indian coming down the wicket and this upset their line,” he observed. He rated Bedi as the best spinner he ever saw: “he could bowl the ball however he wanted. It would always land in the same place. Bedi was able to turn the ball three ways; he could give it a little turn, bigger turn, and then bounce and turn.”

The India series was the highlight of Davis’s Test career. He appeared in all five Tests the following year against New Zealand, scoring 466 runs at an average of 58.25. After collapsing for a meagre 133 in the first innings of the Third Test at the Kensington Oval, the Kiwis built a lead of 289, and required a miracle to save the match. Once again, Davis and Sobers constructed a marathon partnership adding 254, just 20 short of the then all-time West Indian record. Sobers’ 25th Test century (142) lasted six hours and five minutes, whilst Davis was at the wicket for ten hours and two minutes getting his highest first class score of 183. Ironically, he ran himself out as he pushed towards a double century. In the Fourth Test, he was involved in the controversial run out of Lloyd, who had just started to plunder the New Zealand attack.

Despite outstanding performances in back-to-back home series the selectors did not initially include Davis in the squad for the 1973 visit by the Australians. Drafted in for the last two Test matches, Davis’s contributions were not significant. With a young family to focus on, Davis retired from international cricket.

Legacy

Charlie Davis’s career numbers make for interesting discussion. In 29 innings in 15 Test matches, he scored 1301 runs at an average of 54.20, with four centuries and four fifties. Only four West Indians who played at least 15 Tests have a higher batting average than Davis: Headley (22 Tests) 60.83, Weekes (48), 58.61, Sobers (93), 57.78, and Walcott (44), 56.68. Davis’s career coincided with the doldrums period (1969-1973) when the West Indies played 20 Tests without a single victory. Davis never played in a winning Test side, but certainly saved the West Indies from several embarrassing defeats. Fate has not been kind to Davis. He lost an eye following an accident in a soccer game in 1979 and was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis in 1983. The illness took a toll on his assets and his marriage. Yet, Davis, who turned 80 on New Year’s Day and is now in a wheelchair, continues to astonish his doctors with his resilience and stoicism.