In this week’s edition of In Search of West Indies Cricket Roger Seymour looks at an entry in the Forgotten Scoreboard File.

“But sometimes we have to make the best of things, and the way we conduct ourselves when the chips are down …” – Harper Lee, To Kill A Mockingbird

Prologue

“Understand, Garry [Sobers] had one problem,” the speaker is Charlie Davis (The Charlie Davis Story, SN, 18th February, 2024). “He thought the game came to everyone as easy as it came to him. Apart from that, he was the most positive man I ever met. Nothing fazed him. Take for instance, the Fourth Test at Adelaide, on the 1968/69 Tour of Australia….”

West Indies Down Under 1968/69

The West Indies squad for the Australia/New Zealand tour began assembling in Bridgetown, Barbados. Newcomer Mike Findlay, the Windward Islands wicket-keeper, arrived from St Vincent on Wednesday, October 9, followed by part of the Guyanese contingent: Tour Manager Berkeley Gaskin, Masseur Hubert Cromarty, middle order batsman Basil Butcher, and opening batsmen Steve Camacho and Roy Fredericks on Friday. Trinidadians Joey Carew and Charlie Davis arrived on Saturday. The Barbadians: Assistant Manager Keith Walcott, middle order batsman Seymour Nurse, all-rounder David Holford, and fast bowler Richard Edwards joined the team for the Sunday departure to New York. There, Jamaicans: wicket-keeper Jackie Hendriks and fast bowler Lester King, and Guyanese off-spinner Lance Gibbs and middle order batsman Clive Lloyd met the squad for the Monday departure for Sydney.

Barbadians: Captain Garry Sobers, fast bowlers Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith, and middle order batsman Guyanese Rohan Kanhai were already in Australia for the Rothmans International World Double-Wicket Championship. The Sobers and Hall pairing took the title, whilst Kanhai and Griffith failed to win a single match in the five-round tournament played over two weeks at Australia’s then four Test centres and Perth, Western Australia.

The Australian series was the ninth of the decade for the West Indies, who had lost their previous series, 1–0 to England earlier in the year (Sobers’ Declaration at Port-of-Spain, SN, 28 January, 2024). Prior to that stumble, the West Indies had swept aside their opponents of the previous six years. After losing to England (1–0) at home in 1959/60, and away to Australia (2–1) in 1960/61, the West Indies swept India (5–0) in the Caribbean in 1962, beat England (3–1) in the summer of 1963, and defeated the visiting Australians in 1964/65 (2–1). They retained the Wisden Trophy in 1966, beating England (3–1) away, before conquering India (2–0) later that year on the subcontinent. Apart from the controversial loss to England earlier in 1968, the West Indies, led by Sobers, boasting an envied middle order, and the much feared fast bowling duet of Hall and Griffith, were a burgeoning dynasty. Their arrival was highly anticipated, as the local spectators were still raving about the exciting cricket played by Frank Worrell’s side on the previous tour. This was a very experienced squad, boasting a total of 322 Test appearances, with an average age of only 29 years and one month at the start of the first Test.

Whilst the West Indies were in flight, the Western Australian town of Meckering was struck by an earthquake on 14 October, at 10:58:52 local time. It had a moment magnitude of 6.5 on the Richter scale. It affected structures in Perth, the capital of Western Australia, 130 km west of Meckering.

Australia were led by dour opening batsman Bill Lawry, who had been appointed captain for the Third Test of the 1967/68 home series versus India after Bobby Simpson announced his retirement from first class cricket. Under Lawry, the Australians had retained the Ashes in the cold and wet summer of 1968 in a drawn series (1–1).

The West Indies arrived in Sydney on Tuesday 15 October and after a day’s rest flew to Perth, where they boarded a train to Kalgoorlie, a gold-mining town on the edge of Great Victoria Desert. It was the start of a long arduous tour. After disposing of the Western Australian Country XI by an innings in two days, the visitors beat the defending Sheffield Shield Champion Western Australia by six wickets, then succumbed to a Combined XI by seven wickets, as they raced to 354 in four hours and ten minutes behind undefeated centuries from Ian Chappell (188*) and Paul Sheahan (111*), after Butcher (115 & 172) and Kanhai (172*) in the second innings had seemingly guaranteed at least a draw.

In the next match, a young South Australia state team handed the tourists their second consecutive defeat; this time by ten wickets, with a day to spare, as another century by Chappell and a seven-wicket haul by leg spinner Terry Jenner led the way. A draw against the Victoria state team was followed by a confidence boosting victory over New South Wales by nine wickets, with Camacho and Sobers passing the century mark. In the last first-class match before the First Test, the West Indies were saved from another possible embarrassing defeat against Queensland by second innings hundreds from Fredericks and Butcher

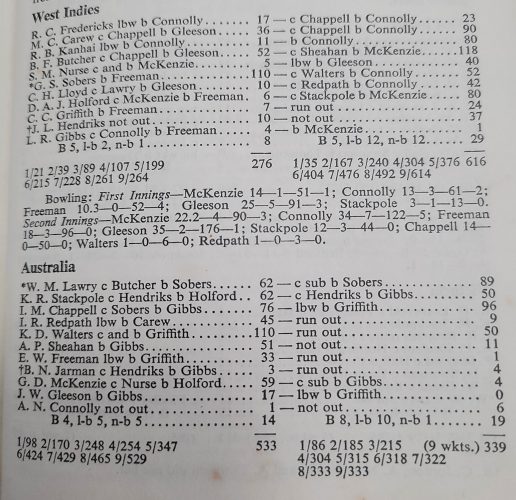

First Test, Brisbane, Queensland, December, 6, 7, 8, 10. Scores: West Indies, 296; Kanhai, 94, Carew, 83, & 353, Lloyd, 129, Carew, 71*, J Gleeson, five for 122. Australia, 284; Lawry, 105, Chappell, 117, Gibbs, five for 88, &, 240, Chappell, 50, Sobers, six for 73. West Indies won by 125 runs, with a day to spare. After winning the toss and batting first on a pitch which broke up as the match progressed, the West Indies took the series lead behind the combined haul of 15 wickets by Gibbs (8) and Sobers (7), and Lloyd’s match-deciding hundred.

The next first class encounter, a drawn match with South Australia, after consecutive seven-wicket wins against Country XIs in two-day fixtures, saw the visitors struggle once again with the bat. After the State side posted 484, mainly due to Chappell’s 180, and Skipper Les Favell’s knock of 113, the West Indies lumbered to 281 – Davis, 69, & Findlay, 59, and 219 for seven.

Within a fortnight and the dawn of the New Year, the West Indies found themselves in a desperate position, down 1–2, in the Test series.

Second Test, Melbourne, Victoria, December, 26, 27, 28, 30. Scores: West Indies, 200; Fredericks, 76, G McKenzie, eight for 71, & 280, Nurse, 74, Sobers, 67, Gleeson, five for 61. Australia, 510; Lawry, 205, Chappell, 165, (fifth in as many matches versus the West Indies), D Walters, 76. Australia won by an innings and 30 runs. First, McKenzie, and then Gleeson destroyed the West Indies batting lineup, and only a fifth wicket stand of 134 in the second innings by Nurse and Sobers prevented a larger margin of defeat.

Third Test, Sydney, New South Wales, January, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8. Scores: West Indies, 264; Lloyd, 50, & 324, Butcher, 101, Kanhai, 69. Australia, 547; Walters, 118, I Redpath, 80, E Freeman, 76, & 42 without loss. Australia won by ten wickets. As in the previous Test, the West Indies’ batsmen failed to apply themselves in the first innings, and then the last four Australian wickets added 198 runs to put the match out of reach.

After drawing with Tasmania, which was highlighted by Kanhai’s 151, an unbroken second innings opening partnership by 147 between Fredericks (70*) and Carew (74*), and a fine century (114) from Tasmania’s Captain Yorkshireman John Hampshire (who was coaching there), the visitors beat a Combined XI by ten wickets in the final first-class match before the critical Fourth Test. Sobers hammered an undefeated 121 in 99 minutes, before declaring at 351 for five. Lloyd (73) and Butcher (57) were the other significant contributors to the score. The Combined XI were dismissed for 152 and 216, with Hampshire hitting a defiant 92 in the second innings.

Fourth Test, Adelaide, South Australia, January, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29. For the fourth time in a row, Sobers called “heads”, won his third coin flip and elected to bat on a pitch described as “a heartless strip for the bowlers” by Australian sportswriter, Phil Tressider, in his book on the tour, “Captains on a See-Saw”. In the sweltering heat of 96 degrees Fahrenheit, the stage was set for the visitors, who replaced Edwards and Hall with Griffith and Holford, to rebound. It was not to be. The pattern of the previous two Tests was repeated. The West Indies batsmen failed to apply themselves and were dismissed by rash strokes. Alan Connolly trapped Fredericks and Kanhai LBW, and when Nurse was spectacularly caught and bowled by McKenzie, the visitors were 107 for four, just after lunch. Sobers then joined Butcher, and dominated the proceedings from thereon. In two hours and 12 minutes, the captain tore the Australian attack to shreds, smashing two sixes and 14 fours on the way to his 20th Test century.

Almost five decades later, Tony Cozier, in his weekly newspaper column, ‘Cozier on Sunday’ – “Late night out no problem for Gayle, Sobers” (SN, 20 March, 2016) – provided some colourful backdrop for Sobers’ century. “Two nights before the Adelaide Test of the 1968-69 series, he [Sobers] joined Dr Rudi Webster [who would go on to become a world famous sports psychologist], a fellow Barbadian who had bowled fast for Warwickshire in the county championship and was then practicing in Australia, and myself for a night out. We were about to call it quits when Sobers talked us into heading to the Arkaba, a hotel owned by Murray Sargent, a former South Australia player Sobers knew from his time with the state team a few years earlier.

“It must have been two a.m. when he finally accepted our concerns that the Test was imminent and agreed to head back to the hotel, proclaiming that he felt ‘good and relaxed’ and promising a hundred. He duly delivered, compiling 110 on the first day without any problems.”

Despite Sobers’ heroics, and useful support from Butcher (52) in a fifth wicket partnership of 92, the West Indies could only muster 276 in five hours, on a perfect wicket for batting.

Australia began the second day on 37 without loss and duly turned the screws on the West Indies, scoring 387 runs. The hosts headed for the rest day, perfectly poised on 424 for six, with Walters, 85 and Jarman, 0, at the wicket. Fifties from Lawry, Stackpole, Chappell and Sheahan had decidedly taken the match and the series away from the visitors. On the third day, Monday, 27 January, Australia Day, the two teams lined up on the field for a ceremony, and Sir Donald Bradman, flanked by the two captains raised the Australian flag. It was an ominous start to the day. When Griffith captured Walters’ wicket, caught and bowled for 110, the hosts were 465 for eight, leading by 189. It was now Mckenzie’s turn to pile on the frustration, as he compiled 59, occupying the crease for an hour and a half before being the last wicket to fall with the score on 533. The West Indies, 257 in arrears, had averaged 267 in their last four innings. The Australians probably placed a call to the engraver to prepare the plate for the Sir Frank Worrell Trophy.

The West Indies settled down to the task at hand, avoiding another embarrassing defeat. By the close, they had raced to 261 for three, with Butcher, 44, and night watchman, Griffith, 10. The fightback was led by Carew (90) and Kanhai (80) in a second-wicket partnership of 132. Bogeyman of the previous two Tests, Gleeson, conceded 98 runs from 19 wicket-less overs, as only Connolly, adapting to medium pace off cutters off a shortened run, commanded any respect, whilst taking the three wickets to fall; dismissing Kanhai with an unplayable ball.

The fourth day belonged to the West Indies. They continued to feast on the Australian bowling, as Griffith stuck around for an hour before he was run out. Nurse’s innings of 40, a 45-minute cameo of fluent drives with four boundaries was recorded by the 1970 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack as “the best innings of the match” before he was given out LBW to Gleeson. 376 for five. Sobers joined Butcher, who notched his second consecutive second innings century of the series before lofting a McKenzie delivery into the safe hands of Sheahan at cover. 404 for six.

Once again, Sobers put on a fine display of hitting, singling out Gleeson for special attention in six overs, as “he extracted eight boundaries to reach a sizzling 50 in 74 minutes”, according to Tressider. Sobers and Lloyd added 72 for the seventh wicket before the former departed to a mistimed shot off Connolly offering the easiest of catches to Walters. When Lloyd followed soon after for 42, the Australians must have breathed a collective sigh of relief which turned out to be short-lived. Holford and Hendriks (who required a runner halfway through his innings) then joined the fray, and in two hours and 20 minutes added 122 for the ninth wicket, eclipsing the previous record set by Jerry Alexander (another Jamaican wicketkeeper) and Wes Hall in the famous Tied Test at Brisbane in the 1960/61 tour. Holford led the way with some attractive strokes before he was caught by Stackpole in the slips, a juggling effort, off the last ball of the day, for 80. 614 for nine. It was the highest ever total compiled by the West Indies against Australia, whose bowlers had not experienced such a pommelling since the 1928/29 English team led by Percy Chapman had accumulated 636 at Sydney.

Fifth day. The West Indies added two more runs, before McKenzie bowled Gibbs, leaving the hosts a target of 360 in five and three-quarter hours to seal the series. An explosive start by Lawry and Stackpole posted 86 on the scoreboard, with the 50 partnership coming in 30 minutes, as Sobers first three overs cost 37 runs. At lunch, the Australians were 106 for one. When play resumed, Nurse emerged with the wicket-keeper gloves, and Davis and Camacho appeared as the emergency fieldsmen for Kanhai and Hendriks. The plundering of the West Indies bowling continued as Lawry and Chappell added 99 for the second wicket, before the former on 89, pulled Sobers, then bowling spin, straight to Davis fielding forward of square-leg.

Controversy then erupted as Griffith stopped during his run up, swivelled and swiped the bails at the non-striker’s end to run out Redpath, who had been backing up by almost a yard, as the Australians stole sharp singles to keep the score ticking along. (It was later confirmed that Sobers apologised to Lawry in the Australian dressing room at the tea interval.)

When the last hour commenced, in which 15 overs had to be bowled, Australia were 298 for three requiring 62 from 120 deliveries. Griffith trapped Chappell LBW for 96, curtailing a sixth century against the tourists, and then in 15 minutes, the match swung again. Walters, Freeman and Jarman were all run out by a combination of good fielding and bad calling by Sheahan, who was involved in all three dismissals. The Australians slumped from 315 for five to 322 for seven. Any one of four results became possible.

McKenzie arrived at the crease with specific instructions from Lawry “to hang on”. Twenty-five minutes later he skied a catch off Gibbs, and when Griffith trapped Gleeson LBW, Australia were in dire straits at 333 for nine. Twenty balls remained.

Tressider observed, “On the very same ground eight years before the one and only ‘Slasher’ Mackay and lastman Lindsay Kline played out their epic final 90-minute stand to rob the West Indies of a victory that would have levelled the series. History was about to repeat itself.”

Sobers took the new ball, but his efforts to last man Connolly went mostly down the leg-side. A long conference was held by the West Indies. Griffith was bestowed the honour of the final over. His eight deliveries (Australia were still bowling eight-ball overs) were right on target, but Sheahan held firm. Match drawn.

Sobers declared, “it was the most exciting game I have played in, next to the tied Test.”

Epilogue

“After Australia had completed their first innings, we were in a hopeless position, behind by more than 250 runs, and about to lose the series. Sobers looked around the dressing room and addressed the team along these lines, ‘Okay, let’s show them what we can do. Carew, you and Fredericks will give us an opening partnership of at least 80. Lal [Sobers often referred to Kanhai – middle name Babulal – as Lal] you will make 100. Butcher, you give us another big 50. Seymour, you are due for a century. Clive, David, and me will contribute 50 each. Hendriks and Charlie [Griffith] will chip in with 20 each. That should give us about 600, enough of a lead for us to bowl them out and level the series,” Davis stated. “The man is a genius.”

Notes

The aggregate of 1,764 runs scored in the Test had been exceeded on only two previous occasions: South Africa versus England (1,981) at Durban in March 1939, and West Indies versus England (1,815) at Kingston, Jamaica in April 1930. The two were Timeless Test matches which lasted 12 and 10 days, respectively, and were both drawn. The Pakistan–England aggregate of 1,768 at Rawalpindi in December, 2022 is now third on the list of the highest aggregates in Tests.

In the West Indies second innings, the lowest score of 23 of the first ten batsmen is the best ever in Test match history.

Fifth Test, Sydney, February, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20. Scores: Australia, 619; Walters, 242, Lawry, 151, &, 394, Redpath, 132, Walters, 103. West Indies, 279; Carew, 64, Lloyd, 53, &, 352, Nurse, 137, Sobers, 113. Australia won by 382 runs, took the series 3–1, and regained the Sir Frank Worrell Trophy.

The West Indies series loss was partially attributed to Sobers’ leadership, or lack thereof. He was frequently absent from the team, playing golf, or reportedly courting Pru, his soon-to-be Australian wife. The sad reality was that Hall and Griffith were spent forces and one account estimated that the West Indies had dropped 35 catches during the series. Casting the blame solely on Sobers, who was playing with a shoulder injury and coming off of a decade of continuous cricket was grossly unfair.

In China, nature’s signs have been traditionally understood to foreshadow major events. On 28th July, 1976, an earthquake, with a magnitude of 7.5 on the Richter scale, almost flattened the Chinese industrial city of Tangshan. The death toll, anywhere from 242,000 to 655,000, was thought to be one of the largest natural disasters in recorded history. It violently shook the sickbed of Mao Zedong, the leader of China, 68 miles away in Beijing. Mao died on 9th September, 1976, and on 23rd October, 1976, there was a total solar eclipse over south west Asia. Mao’s passing between a devastating earthquake and an eclipse, marked the end of a dynasty, according to an ancient Chinese belief.

On Tuesday, 18th March, 1969, at 4.15 am UTC, part of the Annular Solar Eclipse was visible in Perth, Western Australia.

On Sunday 23rd March, 1969, the West Indies departed from Auckland International Airport having drawn the three-Test series 1–1, after winning the First Test at Auckland.

The West Indies dynasty of the 1960s had come to an end.

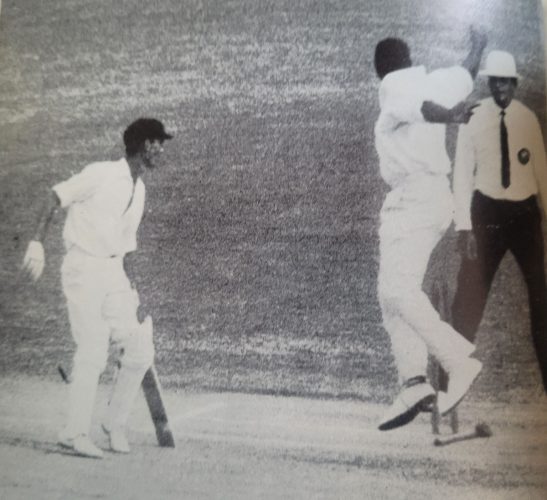

![Kanhai drives John Gleeson during the Fourth Test (Source: Captains on a See-Saw/Phil Tressider [1969])](https://s1.stabroeknews.com/images/2024/03/Kanhai-drives.jpg)