By Roger Seymour

In late August, 1997, during the final round of the Nortel West Indies Youth Cricket Tournament, Mike Findlay, a West Indies Selector, agreed to an interview provided the subject of “West Indies selection” was not broached. At the Courida Bar, Pegasus Hotel, Findlay, the former Test wicket-keeper reminisced on growing up in St Vincent and his involvement in West Indies cricket.

Findlay hails from the small village of Troumaca on the north west-coast of St Vincent, and his early childhood memories were of Vincentians, including his parents, journeying to Aruba to work on the island’s oil refinery. His interest in cricket, which was played everywhere in the rural community, commenced at a very early age; boys played at every opportunity, halting their games only at the fall of darkness. Their bats were carved from coconut branches, and any small fruit, such as limes, oranges, guavas, breadfruit and grapefruit served as balls since they could not afford to buy proper balls.

Beginnings

At the Troumaca Government School, the primary school games teacher, Fandolph Cottle, an uncle, provided encouragement and guidance to the enthusiastic cricketers. Initially, Findlay aspired to be a fast bowler, but after a few weeks, boredom set in and his desire to be more involved in the game led to wicketkeeping. (His father Fitzroy, in Aruba at the time, had been the wicketkeeper for the nearby village of Chateaubelair). On one of the walls of the school he was delighted to find a series of cricket charts, which detailed the various aspects of batting, bowling, fielding, and wicketkeeping. The visual aids were byproducts from the Know The Game series of books, which outlined the basics of many disciplines and hobbies, and were very popular in the 1950s and 1960s. Young Findlay spent many an hour memorising the illustrations to the point where he could close his eyes and visualise every detail.

Whilst still in primary school, Findlay began opening the batting for the Troumaca Village team in matches against other villages and schools. At that time there were no turf wickets in St Vincent, and the game was played on “jute matting” or hardened clay pitches. These competitive and friendly encounters took the village side all over St Vincent, much to Findlay’s delight. Harold Bentick, a pointer in the Baptist Church, loved cricket and skippered the village team. Almost every holiday, Bentick extended an official invitation to Layou, another west coast village, promising to ‘overwhelm you with hospitality’ at the highly anticipated match. In his final year in primary school, Findlay was selected for the National Primary XI to play against the St Vincent Grammar School (SVGS).

At the age of 11, Findlay moved to Kingstown, the capital of the archipelago, to attend SVGS. At that time, the 20-odd mile road connecting Troumaca to Kingstown was underdeveloped making daily commuting impossible. The alternative route was via the launch from Troumaca Bay, two miles from the village, which took about two hours to reach Kingstown.

Already quite adept at wicketkeeping when he entered SVGS, Findlay’s passion to improve knew no bounds, and his ascent from keeping for his House in the second year and wearing the gloves for SVGS soon afterwards, was built on application and maximising all resources. Benny Marshall, the school’s headmaster, who he said was, “a stern disciplinarian and cricket fanatic,” coached the school’s team and oversaw net practice which often took place on half concrete pitches. At these sessions, bowlers of varying speeds were rotated, thus Findlay, equipped only with a pair of gloves, learnt to master the art of standing up to both spin and fast bowling. Apart from working on his fitness and wicketkeeping on a daily basis, he read – a trait encouraged by Uncle Fandolph – every book he could find on cricket, especially on keeping and batting, listened keenly to live broadcasts of cricket matches and paid close attention to St Vincent’s outstanding keeper, Garnet Niles. Lithe and tall, and blessed with a pair of good hands, he soon became the school’s football goalkeeper.

In 1960, Findlay represented SVGS at Queen’s Park in Grenada at the biennial Inter-Schools Sports, where the main schools from the Windward Islands competed at athletics, cricket and football. SVGS competed against the Grenada Boys’ Secondary School, Dominica Grammar School and St Mary’s College of St Lucia. The versatile athlete led SVGS to the cricket championship; played in goal; and in track and field, competed in the 400 metres, the relays and leapt to a new school record in the long jump. (Findlay later represented St Vincent and the Grenadines, at football and volleyball, giving up the former, upon being selected for the West Indies). His performances on the cricket pitch earned the 16-year-old Findlay selection for Senior Windward Islands Goodwill Championship held in Dominica later the same year.

“In the 1960s there were not many opportunities for cricketers in the smaller islands. There was hardly any contact between the Windwards and Leewards,” Findlay said. “The Leewards had the Hesketh Bell Shield and the Windwards took part in the Cork Cup. At home, we had an inter-village competition where most of the batsmen were sluggers and the bowlers were medium pacers. At that time, the West Indies Cricket Board of Control hardly paid any attention to the smaller islands. The first person to highlight our cricket was a Barbadian sports journalist, Don Norville, who wrote for the Barbados Advocate. He started travelling to the islands, and in 1964 visited Dominica, exposing Windward Islands cricket. Up until then only one player from the smaller islands had represented the West Indies in Test cricket, the Vincentian, Alfie Roberts, who had played in one Test in New Zealand in 1956. [The West Indies team for the 1955/56 New Zealand tour was considered a B team since several first choice players were not selected.]

“My first exposure to top cricket was representing the Windward Islands against the 1965 Australians in Grenada, playing against the likes of [Alan] Davidson, [famous wicketkeeper Wally] Grout, and [Bobby] Simpson. In 1966, the first year of the Shell Shield Competition, I was the Combined Islands reserve wicketkeeper to Auckland Hector from St Kitts. In 1967 and 1969 Shell Shield [there was no tournament in 1968], the Leewards and Windwards participated as separate units, playing two matches each, and I kept in all four matches for the Windwards. In 1968, the MCC [in those days England toured under the Marylebone Cricket Club banner] played the Windwards in St Lucia, and I held five catches in a match which had to be abandoned. Both the English Manager, Les Ames [England’s great wicketkeeper/batsman of the 1930s], and the Captain, Colin Cowdrey spoke very favourably of my keeping.”

Findlay’s performance could not have come at a more opportune time. The Windwards/MCC match took place between the Third and Fourth Tests, and the full complement of the West Indies Selection Committee was in attendance. In addition to Findlay’s five snares, including the prize scalp of Geoff Boycott in both innings, Dominica’s middle-order batsman Irving Shillingford, also made a good impression with a solid innings of 69. At the time, West Indies’ incumbent wicketkeeper Jackie Hendriks was injured, and Deryck Murray, who had displaced David Allan (retired in 1966) on the 1963 Tour of England, had returned to the fold in the previous series, the 1966/67 Tour of India, as second keeper. Murray was not enjoying a good series, and would eventually concede 90 byes in England’s eight innings in the five tests.

West Indies team

The West Indies team for the 1968/69 Tour of Australia and New Zealand was announced on 4th April, 1968, the day after the drawn Fifth Test, as England took the series 1-0. Thaddeus Michael Findlay was named as the second wicketkeeper to Hendriks in the 17-member squad. Findlay, with only six first class matches to his name, was the first Windward Islander to earn a place on a West Indian tour. (Alfie Roberts was based in Trinidad at the time of his selection for the 1955/56 Tour of New Zealand.) The discarded Murray was placed on standby, in case Hendriks was declared unfit due to a back strain. The West Indies team departed Barbados for Australia via New York on 12th October.

“My name was being mentioned as West Indies material, but still it was a bit of a surprise when I was selected for the 1968/69 tour of Australia and New Zealand,” he said. “It was a tough tour, but I have great memories. Our tradition was to have a senior player room with a newcomer to the side, and my mentor was Wes Hall. Hendriks spent a lot of time with me passing on his experience.”

Findlay, for the first time, witnessed Gary Sobers in full flight with a bat, an enthralling experience. In the opening first-class match, Sobers tore apart Western Australia’s attack of Test bowlers Graham McKenzie, Laurie Mayne and Tony Lock, with a blistering century of 132 in under two hours, inclusive of 25 boundaries. It was also his initial exposure of keeping to bowlers of the calibre of Hall, Charlie Griffith, Sobers and Lance Gibbs. He paid close attention to Hendriks’ performance behind the stumps in the five tests in Australia and the three in New Zealand, as the West Indies lost the former series 3-1 , and then held the Kiwis to a 1-1 draw. Findlay appeared in ten first-class fixtures on the arduous five-month tour.

Within a month of their return from the Antipodes on March, 26th, 1969, the West Indies were off to England for a half tour – three Test matches – on April, 20th. It was a team in transition, the great side of the 1960s was being dismantled. The pillars of the pace attack, Hall and Griffith were dropped, and Seymour Nurse, the dashing middle-order batsman retired from Test cricket. Rohan Kanhai was unavailable due to a knee injury, while all-rounder David Holford and fast bowlers Richard Edwards and Lester King, members of the Down Under tour party failed to retain their places. Nottinghamshire County, which was losing Sobers for the duration of the tour, indicated to the WI selectors that they would only release Murray (who was also under contract to Notts CCC) for Test matches. Thus, Murray was deemed unavailable for the tour. Findlay, who retained his place, was pleasantly surprised to discover that Dominican Grayson Shillingford (Irving’s cousin), a fast bowler, had been selected among the six first-time tourists.

Test cricket

After losing the First Test by ten wickets at Old Trafford, the West Indies made three changes for the Second Test. Steve Camacho replaced Joey Carew as Roy Fredericks’ opening partner, and the Windward Islanders, Findlay and Shillingford, made their Test debuts, as Hendriks and Maurice Foster, respectively, lost their places. Staged at Lord’s, the Test match commenced on Thursday, 26th June, and was blessed with five days of perfect weather for cricket. The thrilling encounter was drawn, with the West Indies holding the upper hand for the first three days, after scoring 380 and reducing England to 46 for four. Set 332 to win in five hours and 20 overs, England got to 295 for seven wickets.

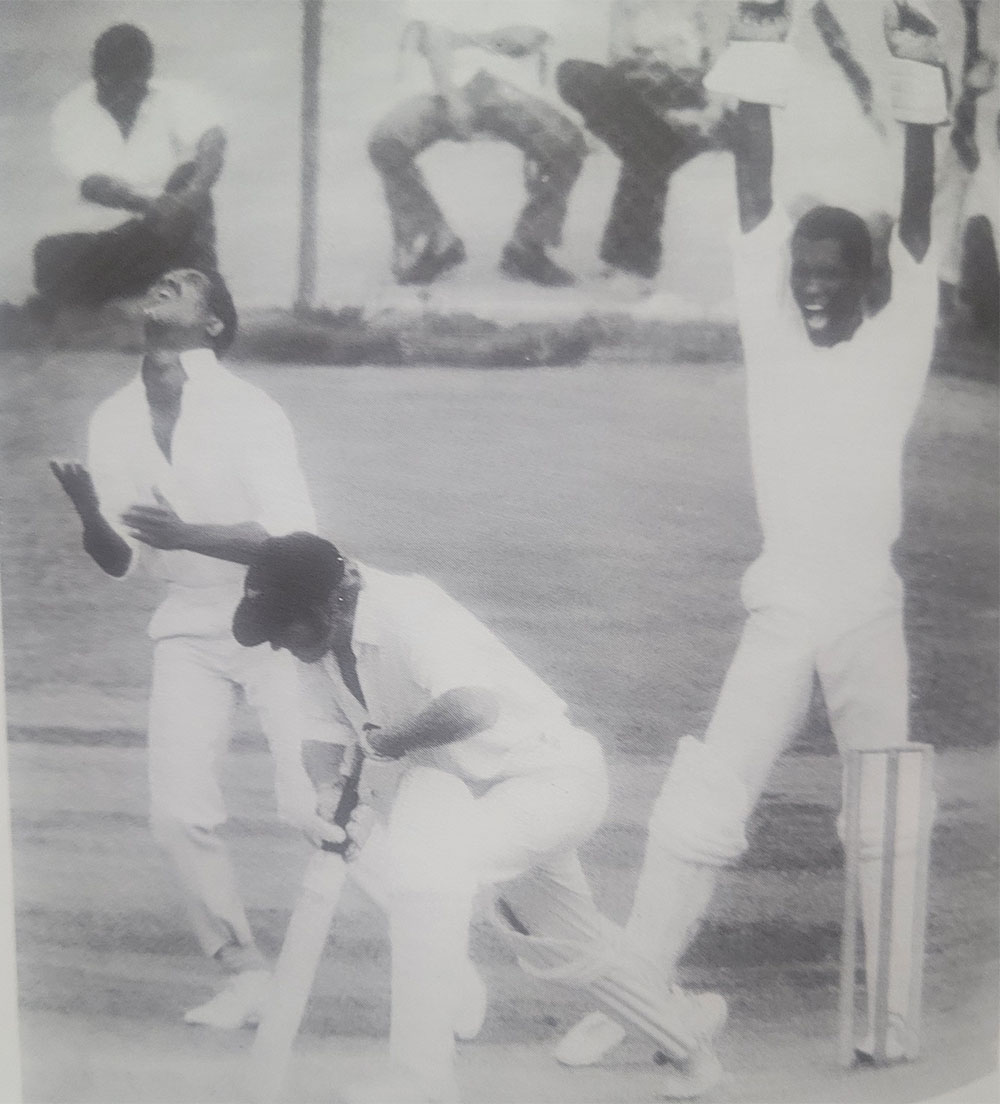

Findlay’s debut Test, in which he took three catches – Boycott off John Shepherd being his first Test victim – and had scores of 23 and 11, was a memorable occasion. Camacho (67) and Fredericks (63) first innings stand of 106, was the highest ever in England, surpassing Allan Rae’s and Jeffrey Stollmeyer’s 103 at Trent Bridge in 1950. Charlie Davis, after being involved in Sobers’ run out, eked out a century (103), the only one scored by a West Indian in the series. John Hampshire, on Test debut, hammered a crucial century (107), as did his fellow Yorkshire men, Skipper Ray Illingworth (111), batting at eight, and Boycott (106), in the second innings’ run chase. On Monday, 30th June, after lunch, the Queen, accompanied by Prince Philip and Prince Charles, met the officials and players of both teams.

The West Indies lost the Third Test in dramatic fashion by 30 runs. Set 303 to win, the visitors were cruising at 219 for three, when Basil Butcher, leading the way, was given out to a disputed catch at the wicket, for 91. With Sobers failing to score, the West Indies capitulated. The Windward Islanders, the last pair, battled for half an hour, adding 28, trying to emulate their English counterparts of David Brown and John Snow, whose 37-run partnership, was the difference in the end. Findlay (16) was the final wicket, as the West Indies lost two Tests in a series versus England for the first time since 1957. It was the sixteenth Test in 18 months for the battle-weary West Indians, their seventh loss, with only two victories. In its summary of the tour, the 1970 Wisden Cricketers Almanac observed, “Hendriks came as the number one wicketkeeper, but he had an unsatisfactory first Test and was replaced by Findlay, who acquitted himself well behind the stumps, and also showed some promise with the bat.”

The West Indies played no Tests in 1970, and when India visited the Caribbean in 1971, Findlay wore the gloves for the first two Tests, the second of which the West Indies lost by seven wickets at the Queen’s Park Oval, despite Jack Noreiga’s famous nine for 95 haul. Findlay appeared to be collateral damage of selectorial panic and confusion, as the West Indies utilised 20 players in the series. His replacement, Desmond Lewis, was considered a better batsman, and had notched scores of 96 and 67 not out, opening the batting for Jamaica in India’s first match on the tour. Lewis appeared to have justified the selectors’ fate in him, with scores of 81 not out on debut, 88, 14, 72 and 4 not out, for an average of 86.33, and opened the batting in the last two Tests.

In 1972, the chopping and changing of the Test side continued, Lewis was discarded (never to play Test cricket again), and Findlay, once again, was behind the stumps for all five drawn Tests against New Zealand. On the first day of the Third Test at Kensington Oval, Findlay saved the West Indies from complete embarrassment. After winning the toss and opting to bat, the West Indies were in dire straits at 52 for six. Findlay joined Sobers and proceeded to lead the rescue act, eventually top scoring with 44 not out, after adding 31 for the last wicket with fellow Windward Islander, Shillingford.

The indecisive West Indies selection policy continued into the 1973 season, as the selectors named two keepers, Findlay and Murray, in the 14-man squad for the First Test versus Australia at Sabina Park, Jamaica. Findlay was chosen with the burden of knowing that he was on trial, and that his replacement was close at hand. His performance was below par, and Murray returned for the next Test, his first appearance since 1968. Findlay’s Test career was over after ten matches, as Murray held the reins until 1980. The young Barbadian David Murray garnered the backup duties for the next two tours of India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka in 1974/75 and Australia in 1975/76.

“One night in 1976 the telephone rang. It was Alvin Corneal calling from Trinidad to inform me that I had been selected for the 1976 tour of England,” Findlay recounted. (Unconfirmed reports later said that David Murray was being disciplined for an incident on the Australian tour). Findlay, whose teammates included Leeward Islanders Andy Roberts and Viv Richards, played in 16 of the 26 first class matches on the tour. Findlay’s swan song on a Maroon tour was a memorable one, as the West Indies romped to a 3-0 victory, a fitting reward for the trail blazer from St Vincent and the Grenadines.