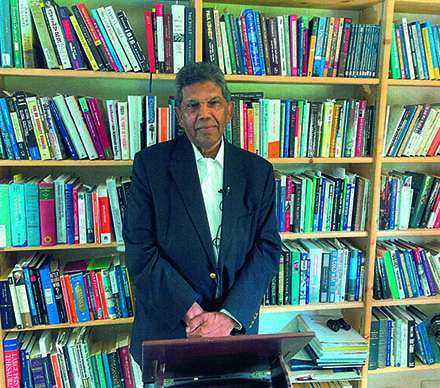

By Dr Bertrand Ramcharan

Seventh Chancellor of the University of Guyana.

Previously Fellow at the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

‘Disorder: Hard Times in the 21st Century’ is the title of a highly regarded 2022 book by Professor Helen Thompson, Professor of Political Economy at Cambridge University. Her telling conclusion in the book is: “How… democracies can be sustained as the likely contests over climate change and energy consumption destabilize them will become the central political question of the coming decade.” We need to add, in the Guyanese context, the lethal ethnic politics in our fragile and contested democracy.

Thompson thinks that in order to mitigate against the possibly destructive nature of the politics to come, collective understanding will need to catch up with what the conjunction of physical realities about energy and the realities of climate change entails. On top of this, there is the ever-present risk of geopolitical conflict, including over territory where critical resources are located – such as Guyana.

Energy, Thompson writes, is the foundation of all economic activity, including the production of food, and is subject to the laws of physics. It needs technological innovation. To succeed, the technology will have to facilitate an energy revolution. Alas, thus far, renewable energy has increased overall energy consumption rather than replacing fossil fuel energy consumption. And, for the moment at least, the attempted energy revolution has been entirely reliant on the fossil fuel energy inputs it seeks to replace, as well as on potentially scarce materials like rare earth metals. It is, she thinks, more likely that there will be a long energy transition than a rapid one.

Thompson cites Angela Merkel, who pointed out that energy change ‘means turning our backs on our entire way of doing business and our entire way of life.” Personal transportation, in particular, will become a site of political conflict: “The future could well entail a return to the pre-[Henry] Fordist world where car ownership was a luxury good and a source of class resentments. At some point, the difficulties around oil and the difficulties of electrifying the transportation sector will meet. Will we, in Guyana, have to go back to railways? Electrified ones?

The 21st century, Thompson writes, has brought a powerful tide of geopolitical, economic, and democratic shocks. Their fallout has led central Banks to create over $25 trillion of new money, brought about a new age of geopolitical competition, destabilized the Middle East, ruptured the European Union, and exposed old political fault lines in the United States.

‘Disorder: Hard Times in the 21st Century’ is a long history of this present political moment. It recounts three histories – one about geopolitics, one about the world economy, and one about western democracies – and explains how in the years of political disorder prior to the COVID pandemic the disruption in each became one big story. It shows how much of this turbulence originated in problems generated by fossil-fuel energies and it explains why, as the green transition takes place, the long-standing predicaments thrown up by energy issues will remain in place.

In the process, in countries with new found energy resources, “large-scale infrastructure projects are open invitations to cronyism when contracts are awarded”. Thompson cites as an example the Obama administration’s provision of funds to a huge construction project to give California a high-speed railway which produced not a new public transport system for the state but a bonanza for consulting firms! Can we think of local examples of this?

Thompson writes that as we go into an unpredictable economic future, overall energy costs will rise and, once again, will act as an inflationary pressure. The inefficiencies of intermittent renewable capacity have thus far often yielded higher electricity prices for consumers.

Politically, energy consumption will invariably cause fierce new distributional conflicts that will reinforce the old ones. In Guyana we already have an intense debate over alleged horizontal inequities across ethnicities.

Where, then, will Guyana be in the energy transition, and when the fossil fuels are gone? We will have had new roads and infrastructures, new cities and schools, new hospitals and health centres. But will our people be better off? Which will prevail: sustainable life-styles or gleaming infrastructure? And how will our people make their living? What will they use for fuel? Will we have saved enough to finance the future of our people, their well -being, their subsistence in dignity?

This is the season of party congresses, in preparation for next year’s general elections. Will our main parties tell us what their visions are for the post-fossil-future of our Dear Land? This is clearly a passing phase. We will have to face the realities of climate change and the replacement of fossil fuels.

We would do well to remember Professor Thompson’s caution that “How… democracies can be sustained as the likely contests over climate change and energy consumption destabilize them will become the central political question of the coming decade.” And let us remember that ours is a fissile country that requires the most delicate handling, with decency and wisdom.

“To Guyana, with Love.”