In this week’s edition of In Search of West Indies Cricket, Part 1.5 of a two-part series, Roger Seymour takes a look behind the scenes of the West Indies’ last-minute rescue act to save an International Cricket Tournament in Toronto, Canada.

The Kargil War

“The year was 1999. The list of cities, places, and names connected by the dots stretched across the globe ….,” the narrator paused, seemingly lost in thought, and then resumed, “… Kashmir, Mumbai, Lahore, New Delhi, Washington, London, Antigua, Singapore, Sahara, Toronto. Apologies if you think I’m referring to John Le Carre’s 1999 novel, ‘Single & Single’, which delves into the workings of an international money-laundering operation. Our yarn involves a holy war, armed conflict, threat of nuclear escalation, money – always money – and the game of cricket. Yes, cricket in far-flung former English colonies and outposts.

“Our narrative began high up in the Himalayas, along the Line of Control which snakes through the stunningly beautiful Kashmir Valley, separating India and Pakistan. This border was closely guarded by soldiers on both sides throughout the year, although the terrain made it difficult to enforce strict border control. Hundreds of mules were utilised by the army in their patrols. However, in the frigid winter months, it was common practice for both armies to regularly descend to lower altitudes to escape the harsh climatic conditions.

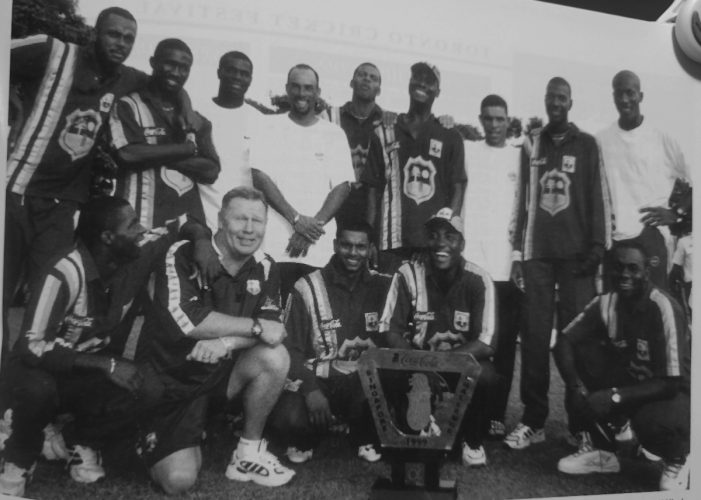

Courtney Walsh, Wavel Hinds, Reon King, Jimmy Adams, Mervyn Dillon, Hendy Bryan, Ricardo Powell,

Adrian Griffith and Nixon McLean; front row: Sherwin Campbell, Dennis Waight (physio), Shivnarine

Chanderpaul, Brian Lara (captain), and Ridley Jacobs; missing are Nehemiah Perry and Clive Lloyd

(manager) (Source: Red Stripe Caribbean Cricket Quarterly October / December 1999 Vol 9 # 4)

“In May, 1999, it was reported that bearded men dressed in traditional garb and topi hats announcing themselves as mujahideen (holy warriors) declared a jihad (holy war) seeking to free Kashmir, and invaded India’s side of the divide. They took control of several mountain peaks in the Kargil range vacated by the Indian army, overlooking the highway which connects Srinagar (southwest) and Leh (southeast). By blocking the highway, they could cut off the only link between Ladakh and the valley.

“In the previous summer, both India and Pakistan had tested atomic bombs, and now, the world held its breath, viewing Kashmir through a nuclear prism, and fearing escalation of the conflict. Independent analysts pointed out that the Pakistani freedom fighters must have had sophisticated military assistance to engage in combat at altitudes of 5,000 metres amidst bitter cold and low oxygen. In some quarters, it was assessed that most of the fighting was done by Pakistani soldiers, and it was not a holy war as was proclaimed.

“Once, India realised that its border had been infiltrated, it launched Operation Vijay (Victory) a massive counterattack. The undeclared war, for the most part, took the form of hand-to-hand combat, resembling trench warfare, and lasted for two months. While the fighting raged, intense diplomatic negotiations between the foreign ministers and meetings between the military leaders failed to produce any resolutions. By the time Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif ordered the withdrawal of his outnumbered troops, much to the consternation of the religious warriors, the corpses of hundreds of soldiers from the two armies littered the Kashmir Valley. When the cease fire was announced in mid-July, it was estimated that the death toll was over 2,000 combatants on both sides.

“This strife was in stark contrast to the diplomatic olive branch Prime Minister Sharif had extended to India’s Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee in February, three months prior, inviting his counterpart to ride a bus across the border to Lahore. There, the two heads of state signed a declaration vowing to resolve bilateral differences, including Kashmir, through negotiation.

“The fallout from the invasion had a ripple effect around the world. Sharif was summoned to Washington for an audience with US President Bill Clinton, where he had to acquiesce to India’s pre-conditions for a cease fire; a withdrawal of Pakistani military back to the Line of Control – couched in face-saving explanations that he would request the holy warriors to withdraw. Sharif had antagonised India, lost Vajpayee’s trust, lost standing with the international community, while many of his countrymen felt humiliated by his Washington directive.

“Whilst bullets were flying in the Kashmir Valley, the two nations were locked in another intense battle, further afield. On 8th June, at Old Trafford, Manchester, England, Pakistan (Winners of Group B) clashed with India (Runners-up of Group A) in the fourth match of the Super Sixes stage of the 1999 ICC World Cup. Pakistan restricted India to 227 for six off 50 overs, but were scuttled for 180 in reply, as India won by 47 runs. Ironically, it was India’s lone victory in their five second round matches, as they finished in the cellar. Pakistan, headed the points table on net run rate, convincingly defeated New Zealand by nine wickets in the semi-final, before suffering a humiliating eight-wicket defeat by Australia in the final.

“India and Pakistan were scheduled to resume their Sahara Cup rivalry in Toronto in September. The series, which had been conceived by the International Management Group (IMG), was entering the penultimate year of a five-year contract. The first sign that the event might be in jeopardy was a statement from Subrata Roy, Chairman of the Indian conglomerate Sahara sponsoring the series. He was quoted in the Indian press on 30th July as saying, ‘We are pained, enraged and disgusted with the developments at Kargil. Sahara can never be associated with anything that is against the interests of our country in any manner.’

“Roy’s pronouncement followed sentiments expressed by Kapil Dev, the former Indian captain and cricket hero, two days earlier, who, after visiting military hospitals in the war zone, declared, ‘India should not play against Pakistan anywhere.’

“The wheels were beginning to come off the Sahara Cup. Andrew Wildblood, Senior Vice-President of IMG, based in London immediately denied the withdrawal of Sahara’s sponsorship when contacted by the Toronto Star newspaper for a comment on the quote from the Sahara Chairman. ‘The news is definitely not accurate. Sahara is concerned over the fighting in Kashmir and assured me today that there is no change in plans. Sahara is faced with a difficulty but it is very premature to say it has withdrawn its support or that the teams will not travel to Toronto. As far as we are concerned, the event is definitely on,’ he told the Star.

“Whether Wildblood was being very optimistic, or just executing a public relations stunt to buy precious time was never ascertained. The Sahara Cup took months of precise planning and execution to pull off. Construction of the four temporary stands, which were erected to accommodate the 5,000 daily spectators expected to attend the matches, had to commence in August for the mid-September tournament. Mike Corley, the head groundsman of Scarborough Cricket Club in Yorkshire and TCCB Deputy Pitches Consultant, had already made several monthly visits to prepare the pitch at the Toronto Cricket, Skating and Curling Club. Millions of dollars worth of television equipment had to be shipped and assembled. Flights and hotels for the teams, officials, IMG management and support staff, Trans World International (TWI) [television production company, subsidiary of IMG] had to be booked long in advance.

“While the clock ticked, Dr Geoff Edwards, President of Canadian Cricket Association (CCA), kept his hopes high, telling the Toronto Star, “If Wildblood says it is on, I think it is on. I am an eternal optimist and it is pivotal for Canadian cricket that this series continues well into the new millennium.” Dr Edwards’s positive thoughts centred around the fact that the CCA had been awarded the 2001 ICC Trophy Tournament, the qualifying competition for ICC affiliates for 2003 ICC World Cup, and IMG had been bankrolling the CCA to the tune of Cdn$100,000, every year that the Sahara Cup was staged in Toronto.

“On the weekend of 21st – 22nd August, in the wake of the Kargil War, the largest and deadliest of the border clashes, the Indian government intervened and barred its cricket team from playing Pakistan in the Sahara Cup. The sponsor soon followed the government’s lead. Anyone who has read Mark McCormack’s (IMG Founder) book ‘What They Don’t Teach You at Harvard Business School’ is keenly aware of IMG’s innovative and resourceful approach to problem solving. With most of the pieces already in place for an event that was no longer happening, Wildblood set to work behind the scenes hoping to salvage it.

“Wildwood made dozens of international phone calls and followed up with dozens of emails to Mumbai, Lahore and Antigua, enduring sleepless nights as he communicated within multiple time zones.

No doubt, one of his first calls was to Stephen Camacho, the former West Indies and Guyana opening batsman, then the Chief Executive of the West Indies Cricket Board (WICB), and based in St John’s, Antigua.

Singapore

“While Wildwood tried to pull a rabbit out a hat, the West Indies cricket team headed off to Singapore, the latest former English colony to host an international cricket tournament. The Singapore Cricket Club had been established in 1837, and once served as a regular host for Australian teams on their way to England for Ashes series. The Coca-Cola Singapore Challenge ODI tournament involved the West Indies, India and Zimbabwe.

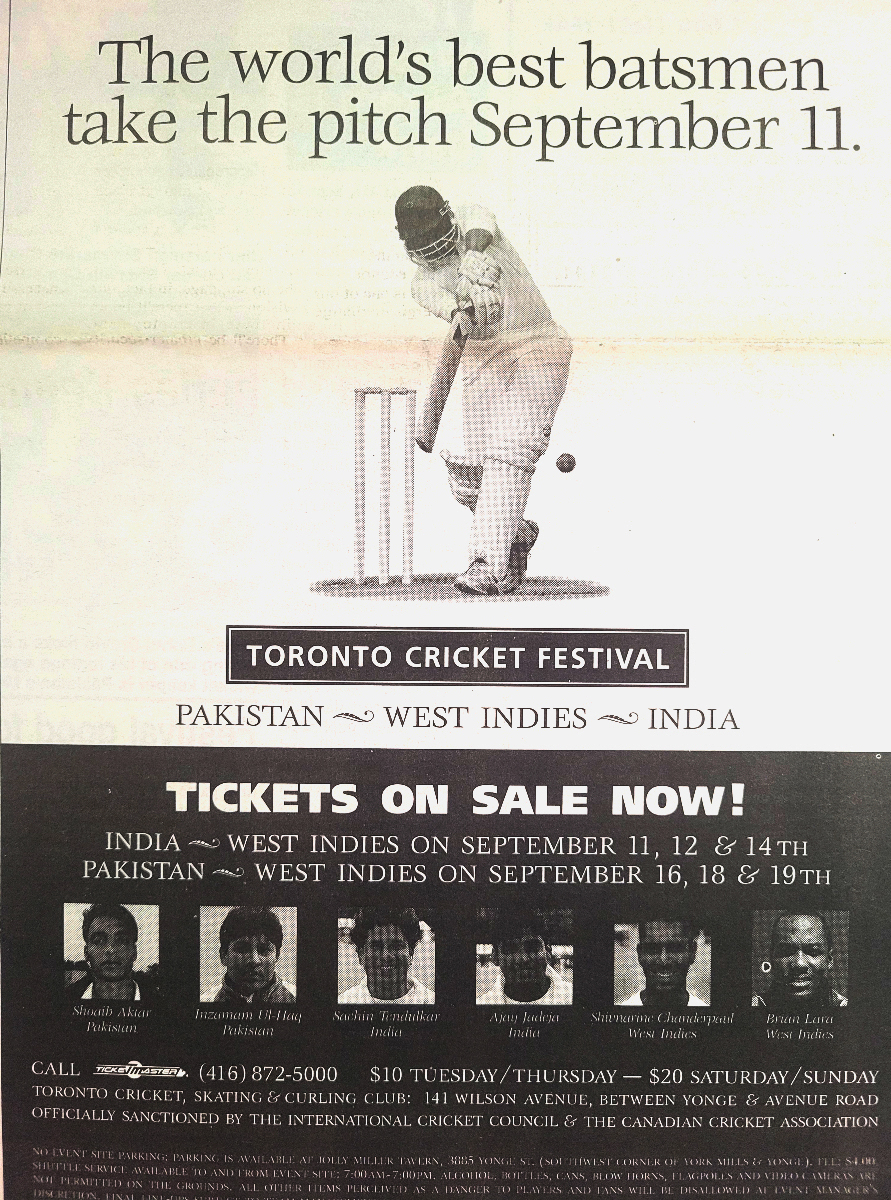

“On 31st August, IMG Offices in Toronto, issued a press release advising that the West Indies, India and Pakistan were to play in Toronto on September 11, 12, 14, 16, 18, 19. It was billed as the Toronto Cricket Festival ‘99 and said to be replacing the annual series of matches between Pakistan and India which were suspended until 2000.

“Across the globe, on 2nd September, the West Indies defeated Zimbabwe in the first match. Scores: Zimbabwe, 244 for nine off 50 overs; West Indies, 247 for four off 43.4 overs. Two days later, the West

Indies defeated a weakened India side (no Tendulkar) by 42 runs. Scores: West Indies 196 for seven off 30 overs; India, 154 for eight off 30 overs. The final, West Indies vs India (who also defeated Zimbabwe), played on 7th September, was abandoned after 38.2 overs due to the weather, with India on 149 for six wickets. The final was replayed the next day. Scores: India, 254 for six off 50 overs, R. Dravid, 103*. West Indies, 255 for six off 47.4 overs. West Indies won by four wickets.

“The West Indies’ first overseas tournament success in over four years was due to a swashbuckling innings from the 20-year-old Jamaican Ricardo Powell, who arrived at the wicket with his side floundering at 67 for four. Powell’s maiden international century (103) included eight sixes and nine fours as he waylaid the Indian attack. First, Powell added 61 in 9.4 overs for the fifth wicket with Chanderpaul (20), and then 118 for the sixth wicket off 19 overs with Nehemiah Perry 38*. The West Indies and India teams then set off on a very long flight to Toronto. Heading east, the players crossed the International Date Line, losing one day in time.

Canada

“At noon on Friday, 10th September, 1999 the DMC Toronto Cricket Festival held a press conference in the dining room of the Toronto Cricket Skating & Curling Club.

“Andrew Wildwood said, ‘I thought that by including a third team we could save the annual tournament, but there was still a question of what format we should use . But once that was established, we managed to work it out with the countries involved.’ The West Indies and India were scheduled to play three matches in the first week for the DMC Cup, and then the West Indies and Pakistan would also engage in three matches for the DMC Trophy.

“Wildwood noted, ‘IMG has had a strong relationship with the West Cricket Board since 1988 when it became the first cricket board to be represented by our company.’ [TWI, an IMG subsidiary, was the first organisation to televise cricket from the West Indies – In Search of West Indies Cricket, ‘The origin of live televised cricket from the West Indies, 5 November, 2023.]

“At the press conference the cricket festival’s sponsor was introduced. Sudhir Thomas, a young professional expat from India, and the Managing Director of DMC, a Toronto-based computer software company. Also introduced were the captains of India – Saurav Ganguly and the West Indies – Brian Lara; India’s coach Aunshuman Gaekwad and Clive Lloyd West Indies’ Manager/ Coach.

“‘More than a billion television viewers will take in the action,’ stated Bill Sinrich, an IMG Director.

Television coverage for the festival was: ESPN (Asia), ATN (Canada), PTV (Pakistan), SABC (South Africa), ZeeTV (UK) and Kelly Broadcasting (USA). Radio commentary was being provided by Pakistan Broadcasting Corp, and the Caribbean News Network.

“IMG officials refused to disclose the financial arrangements at the press conference, other than that the winner of each game would collect Cdn$20,000, and there were also prizes for each man of the match. The following day the Toronto Star reported that Pakistan Cricket Board Chairman Mujeeb-ur-Rehman was on the record as stating that his country was receiving match fees of US$500,000. It was later disclosed that TWI had signed the West Indies to play three matches against each team for US$200,000.”