Introduction

The issue of contracted employees attached to the Office of the President as well as the level of salaries offered has been the subject of a recent intense debate in the National Assembly. The outcome of the debate was that the Assembly did not approve of amounts totalling $150 million sought by way of supplementary estimates for 2012 to meet the wages and salaries of some of these employees.

Today, we look the Public Service Commission (PSC), an institution of the State that the public looks forward to in ensuring that there is a fair, equitable and transparent system for government employment.

Composition of the PSC

* Three appointed by the President after meaningful consultations with the Leader of the Opposition;

* Two appointed by the President upon nomination by the National Assembly after it has consulted such bodies as appear to it to represent public officers or classes of public officers; and

* One other member appointed by the President in accordance with his own deliberate judgment.

The tenure of appointment is for three years or such earlier period as specified by the instrument of appointment. A person who is a public officer is not eligible for appointment to the Commission. “Public officer” is defined as the holder of any public office and includes any person appointed to act in any such office. “Public office” is an office of emolument in the public service and includes the office of a teacher in the public service and any office in the Police Force. The Constitution is, however, silent on the question of re-appointment and ineligibility after serving for a specified period, say two consecutive terms.

Functions of the PSC

The Constitution vests with PSC the power to make appointments to public offices, and to remove and to exercise disciplinary control over persons holding or acting in such offices. However, the authority to appoint the following persons vests with the President:

* Auditor General, Commissioner of Police, Solicitor General; Permanent Secretary, Secretary to the Cabinet, Ambassador and High Commissioner;

* Principal representatives of Guyana in any other country or accredited to any international organization; and

* Such offices in the department responsible for external affairs, as may be designated from to time by the President.

In addition, appointments to the personal staff of the President can only be made with the concurrence of the President.

One of our inheritances from the British is that of a Public Service which is politically neutral and “permanent”. Governments may come and go, but it is the Public Service that remains to serve the government of the day. It provides the institutional memory for continuity. This apart, the model provides a high degree of assurance that government employment practices are fair, equitable and transparent. There are detailed rules for the recruitment, transfer, promotion and removal of public officers.

Analysis of the Guyana situation

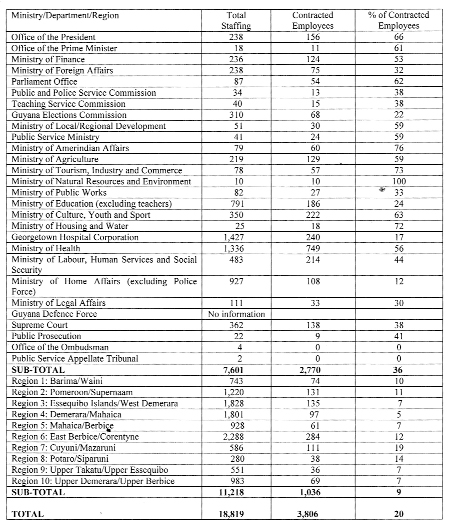

A review of the estimates of revenue and expenditure for 2012, as presented in the National Assembly, revealed that a significant number of persons are employed on a contractual basis, and therefore the PSC would not have been involved in their recruitment and the fixing of their remuneration. The table below, which does not include teachers and police, summarises the staffing for 2012:

The Office of the President has 156 contracted employees out of 238, or nearly two-thirds, and their emoluments account for 88 per cent of the wages and salaries paid by that office. Similarly, at the Ministry of Finance, contracted employees account for a little over 50 per cent (124 out of 236) and their emoluments represent 69 per cent of the wages and salaries.

In his book, “Commonwealth Caribbean Public Law”, Prof. Albert Fiadjoe made the interesting observation that the constitutional intention of a neutral depoliticised Public Service is somewhat diluted by the opportunity available to governments to create posts outside the public service umbrella and therefore outside the protection afforded by the Constitution via the Service Commissions. He quoted Prof. Carnegie as having observed that this practice “seems to be that of compromise between the politicians’ felt need to have control over those who have to execute their policies and the tradition of the politically neutrality of the Public Service”.

Prof. Carnegie’s observation seems relevant in any analysis of the Guyana situation, though he might not have anticipated the scale of such a practice. What appears to be the case is that there are two types of public service: the traditional public service over which the PSC has jurisdiction over the appointment, discipline and removal of public officers; and a parallel public service comprising contracted employees recruited and remunerated outside of the constitutionally mandated PSC umbrella with enhanced emoluments and conditions of service.

Is this practice reflective of a need to exercise political control or is it a lack of trust in the traditional public service? Is it a question of pay whereby the Government finds it difficult to attract and retain the necessary skills? Or is the traditional public service so inefficient and bureaucratic that there is a need to put in place an alternative mechanism to lift standards of efficiency and performance?

One of the main criticisms of Public Services generally is that they have been slow to respond and adapt to the rapidly changing environment in which governments operate, especially as regards resource constraints they face in the delivery of services. The UK government has made stringent efforts since the days of Margaret Thatcher to make the service more efficient, accountable, and customer-oriented, and to adopt a more business management approach. For example, in June 2009, a UK parliamentary report entitled “Good Government” assessed the effectiveness of government against five requirements identified as prerequisites for good government: good people, good process, good accountability, good performance and good standards.

The report emphasized the importance of recruiting and cultivating the right people so that they can deploy their skills to the work of government. This equally applies to government ministers, civil servants and public servants more generally. High ethical standards in public life are also vital in ensuring public trust and confidence in governing institutions. The report concluded that the civil service was not unfit for the purpose, but there was much scope to improve operational capability.

Conclusion

Regardless of the justification offered, the practice of employing contracted employees on a scale undertaken by the Government dilutes the authority of the PSC and is very costly to the taxpayers. The whole effort appears to be one of short-termism in that should there be a change in government, most of these employees, especially if they are politically aligned, are likely to be replaced by a new set of contracted employees. This could very well be a never ending cycle. Meanwhile, the traditional Public Service is likely to die a slow death.

The ultimate solution is reforming the Public Service so that there is a uniform system in place for the appointment, discipline and removal of public officers. Barbados started the process of phasing out of casual employees in 1997 by establishing such posts as public office posts within the meaning of its Constitution. In addition, the suggestion of Sir Carlise Burton et al about the strengthening of the human resource capability through the following, is worthy of serious consideration:

* Development of appropriate human resource policy statements;

* Review of existing orders, rules and regulations;

* Development of human resource information systems;

* Development of appropriate performance appraisal systems;

* Strengthening training and development functions, and providing more managerial training for middle and senior level managers; and development of a core of personnel technicians to work in line with ministries.