Globalisation and Sugar

Today’s truly fundamental defining feature of the condition of the Guyana sugar industry (and Guysuco more particularly), is that, several decades ago it became mature, and from all appearances since the 1960s, it has entered a long-run declining phase, as described in classic industrial and firm theories. Cane sugar production can no longer reclaim the glory that it had earlier enjoyed in Guyana and the Caribbean, when plantation/estate sugar production was emerging as the leading edge of capitalistic modes of development (especially the emergence of global transnational enterprises and their internationalisation) as world markets for goods, services, capital and finance were being rapidly created. If truth be told, those economic outcomes of plantation enterprise were stupendous and in my view represent the decisive precursors to the present age of globalisation.

Several contributory factors are responsible for the present situation of the cane sugar industry in Guyana, and for that matter worldwide. Here, I would stress two: 1) the emergence of sugar extraction from other plant sources (particularly beet) and 2) the growth of a wide range of substitutes for sugar, both caloric (particularly high-fructose corn syrup) and non-caloric (particularly artificial sweeteners like Splenda and Equal). Importantly, these alternate sweeteners have found wide acceptance among consumers everywhere.

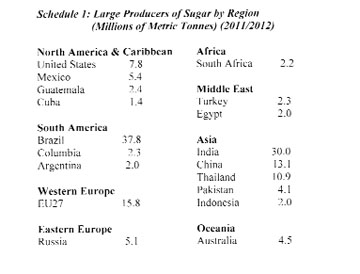

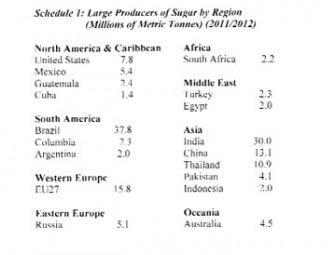

At the outset of the current series of columns on sugar, I had listed the ten (10) leading global producers of sugar (See Stabroek News, September 9, 2012). Actually, however, there are today about a score of countries, located on all the continents and major regions of the world, which are producing annually cane or beet sugar in amounts well in excess of 1 million metric tonnes. (See Schedule below)

While production in those countries does not necessarily come from a sole monopoly producer, what the Schedule suggests is that the total volume of their domestic production could represent the possibilities for the domestic market to be used as a platform for achieving economies of scale.

Economies of Scale

What are economies of scale? Economies of scale in sugar production require that, as more sugar is produced (that is, the scale of production expands), on average less input costs are incurred. Several factors would make this likely. Particularly, economists would expect a greater division of labour, an increased ability to enhance labour skills, the possibilities of learning by doing, more innovation, the wider application of technology, funding of Research and Development, as well as an increased resort to specialisation in the production, distribution and marketing of sugar.

Readers should be aware that such economies of scale can be classed as either internal or external to Guysuco. When they are internal, this requires that the economies of scale are achieved within Guysuco. When they are external, this requires that all enterprises operating within the sugar industry as a whole (for example, the independent cane farmers) would both benefit from, as well as contribute to the benefits of reduction in costs, due to the expanding scope of the industry.

Economists would also normally expect that, with the reduction of the long run average cost of production, which economies of scale permit, this would in turn contribute positively to Guyana’s economic growth. However, readers should recall the observation made above: the physical limitation of Guyana’s size, constrains the scale or availability (hectares) of land suitable for commercially profitable cane sugar cultivation.

In the above sense therefore, searching for economies of scale in sugar production in Guyana at levels of output well below half-a-million metric tonnes annually, would be elusive. It reveals the basic illogic underlying the US$185 million plus Skeldon Sugar Modernization Project (SSMP). Given the global configuration of the leading competitive sugar producers as presented in the Schedule above, even in the best of circumstances the gains from economies of scale at an output of 450,000 tonnes annually would be marginal on a global scale. There is no real hope for Guyana becoming again a competitive global exporter, given the present demand and supply structure of the world sugar market.

This constraint is reinforced by the consideration that Guyana’s sugar production is principally for export (that is, for sale in external markets Guyana cannot control). As I shall more fully explain in subsequent columns, the future configuration of our sugar industry must therefore, necessarily centre on this fundamental illogic. Otherwise, if Guysuco remains a state-owned entity there is grave danger of the state directing scarce resources to sugar for purely political reasons, particularly as this burden can be passed on (through taxation) to the citizenry at large.

Conclusion

In previous columns on sugar I had examined the key performance indicators of the industry in some detail. I do not intend to repeat this in the current evaluation, since only one full crop year (2011) and the First Crop for 2012 have elapsed since then. However, for readers’ benefit I shall briefly refer to these as part of next week’s column.