2019 Global Corruption Barometer Report for Latin America and the Caribbean

At a rally to launch the APNU+AFC election campaign, the President stated that constitutional reform would be a priority if the coalition wins the forthcoming elections. In apparent reference to the 21 December 2018 no confidence vote, he asserted that one of the reasons for doing so is to ensure that ‘the nonsense they tried with us over the last 12 months does not happen again’. Critics would argue that in 2014, when in opposition, the President’s party, APNU, joined forces with the AFC to table a motion of no confidence in the Government. The only difference was that before the motion could have been debated and voted on, former President Donald Ramotar prorogued Parliament, then dissolved it, thereby paving the way for the historic May 2015 national and regional elections.

In any system of democratic governance, democracy and accountability are the twin sides of the same coin. In considering the relationship between the two, it is more often than not found that democracy leads to accountability which in turn leads to development. A lack of democracy leads to a lack of accountability which in turn leads to a lack of development and hence economic stagnation. It also breeds corrupt behaviour among politicians and senior public officials. Democracy starts with the casting of the ballot in a free, fair and transparent process. The party or coalition of parties that wins the election is responsible for managing the affairs of the State on behalf of the citizens for a specified period, usually four to five years. If an elected government fails to honour its obligations at any time during its tenure of office, citizens have the right to remove that government from office. They invariably do so through their elected representatives in the legislature via a vote of no confidence in the government, especially where there is a minority or near minority government. It follows that a provision for a vote of no confidence, or any variant of it, is indispensable to any system of democratic governance.

Last Thursday, Transparency International (TI) published its 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) which is the leading global indicator of public sector corruption. The CPI provides an annual snapshot of the relative degree of corruption among the countries surveyed by independent and reputable institutions, such as the Economic Intelligence Unit, World Bank, the World Economic Forum, African Development Bank and Varieties of Democracy. The results, when computed/tabulated, correlate well and provide a reasonable basis to assess the extent to which corruption is perceived to exist in the countries involved.

Overall 2019 CPI scores

For the 2019 CPI, 13 data sources were used, and 180 countries were assessed. According to TI, more than two-thirds of countries scored below 50, with an average score of only 43. Since 2012, only 22 countries have significantly improved their scores, including Estonia, Greece and Guyana. Twenty-one have shown significant declines, including Australia, Canada and Nicaragua. The United States dropped two percentage points down to 69, the lowest in eight years at a time when trust in the U.S. Government was only 17 percent. Similarly, Canada has dropped four percentage points to 77 and seven points since 2012.

The countries scoring the highest on the 2019 CPI are New Zealand (87), Denmark (87) Finland (86), Singapore (85), Sweden (85) and Switzerland (85). On the other hand, the countries that scored the lowest are Somalia (9), South Sudan (12) and Syria (13), Yemen (15), Venezuela (16), Sudan (16), Equatorial Guinea (16) and Afghanistan (16). On an overall basis, the majority of countries have shown little or no improvement in their CPI scores. According to TI, ‘[o]ur analysis shows that corruption is more pervasive in countries where big money can flow freely in electoral campaigns and where governments listen only to the voices of wealthy and well-connected individuals’.

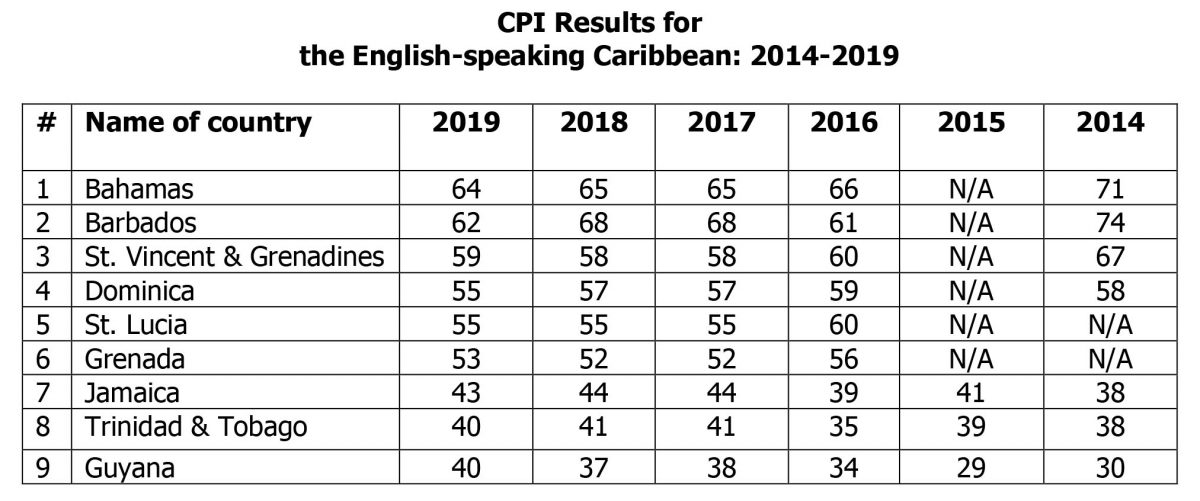

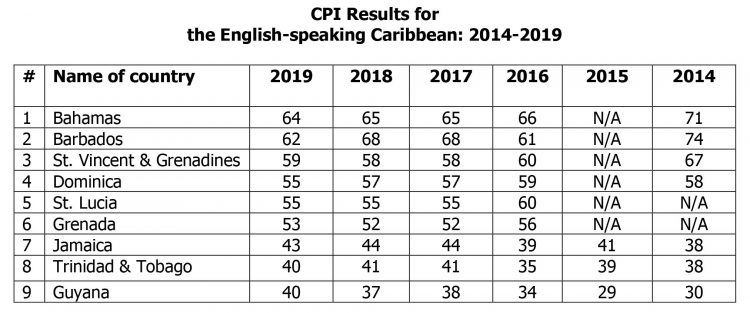

CPI scores for the English-speaking Caribbean

Here in the Caribbean, Guyana scored 40 on a scale 0 to 100, compared with 37 in 2018, joining Greece and Estonia that have also shown improvements in their CPI scores. It also ranked 85 among the of 180 countries surveyed. In fact, Guyana has improved by 12 percentage points since 2012 from a score of 28 to 40. According to Dr. Troy Thomas, President of Transparency Institute Guyana Inc., the current Administration has taken several measures that would have contributed Guyana’s good showing. These include:

► Making petroleum contracts publicly available;

► Dismissing employees found guilty of corruption;

► Halting a major contract for parking meters in the capital

city, which violated the procurement laws, following protests

by citizens;

► Re-establishing the Integrity Commission;

► Updating the code of conduct for public offcials;

► Appointing the Ombudsman;

► Establishing the State Assets Recovery Agency;

Strengthening anti-money laundering laws;

Passing whistleblower protection legislation; and

Implementing several other interventions with implications for integrity in public life.

To the above, we must add the activation of the Public Procurement Commission and the approval of the National Budget before the beginning of the fiscal year. Dr. Thomas, however, warned that ‘[t]he establishment of anti-corruption agencies and the passage of laws do not necessarily mean that everything is functioning well, or that things are fully operational. These developments are still significant though, and might account for a growing optimism that ending impunity for corruption is finally possible.’

One could legitimately enquire whether Guyana’s score and ranking reflected the events that took place in the aftermath of the no confidence vote as well as the Auditor General’s findings in his leaked report for 2018 which is yet to be officially made public. Suffice it to state that the 2019 CPI was arrived at based on sources of information published within the last two years, with a cut-off date of around August 2019. Therefore, it would not have fully reflected the impact of such events, if at all. We will have to await the publication of the 2020 CPI assessment.

Despite its improved performance on the CPI, Guyana still remained at the bottom of the table for the English-speaking Caribbean, this time joined by Trinidad & Tobago which has dropped one percentage point. According to TI, ‘[w]hile there is still much work to do, the government is demonstrating political will to hold former politicians accountable for the misuse of state resources’. The table below shows the CPI results for the period 2014-2019 for the English-speaking Caribbean:

2019 Global Barometer Report

TI had issued a complementary report last year entitled “2019 Global Corruption Barometer Report for Latin America and the Caribbean”. The report was compiled based on surveys carried out during the first quarter of 2019 of citizens’ views and experiences of corruption. The results show that more than half of all citizens think corruption is getting worse in their country and that their government is doing a bad job at tackling it. A key finding is that:

A lack of political integrity risks undermining democratic foundations… This can be seen in the abuse of electoral processes, such as vote-buying and the spread of fake news, and in the weakening of political institutions. A growing distrust and disappointment in government has contributed to increasing anti-corruption sentiment across the region, but this is empowering populist leaders who frequently make matters worse.

It was the first time that Guyana was included in the survey that assessed the opinions of 890 Guyanese citizens. The key findings were:

40 percent think that corruption increased in the previous 12 months while a similar percentage believe that it has decreased;

67 percent think that the Government is doing a good job at tackling corruption while 29 percent believe that it is doing badly;

42 percent believe that officials of the Police Force are corrupt, followed by Members of Parliament (36%), the offices of the Presidency and Prime Minister (29%), government officials (27%), local government officials (24%), business executives (24%), NGOs (21%), and judges and magistrates (20%);

27 percent of public service users paid a bribe for public services in the previous 12 months; and

82 percent think that ordinary people can make a difference in the fight against corruption.

TI’s recommendations

TI has made the following recommendations for governments to consider if they are to improve their scores and ranking on the CPI:

(a) Conflicts of interest: Reduce the risk of undue influence in policy-making by tightening controls over financial and other interests of government officials; and address “revolving doors”, establish cooling-off periods for former officials and ensure rules are properly enforced and sanctioned.

(b) Political financing: Improve and properly enforce campaign finance regulations to prevent excessive money and influence in politics; disclose political parties’ sources of income, assets and loans; and empower oversight agencies with stronger mandates and appropriate resources.

(c) Electoral integrity: For democracy to be effective against corruption, ensure elections are free and fair; prevent and sanction vote-buying and misinformation campaigns essential to rebuilding trust in government; and ensure citizens can use their vote to punish corrupt politicians.

(d) Lobbying activities: Promote open and meaningful access to decision-making; consult a wider range of groups, beyond well-resourced lobbyists and a few private interests; and ensure lobbying activities are made public and easily accessible.

(e) Preferential treatment: Create mechanisms to ensure that service delivery and public resource allocation are not driven by personal connections or are biased towards special interest groups at the expense of the overall public good.

(f) Citizens’ empowerment: Protect civil liberties and political rights, including freedom of speech, expression and association; engage civil society; and protect citizens, activists, whistleblowers and journalists in monitoring and exposing corruption.

(g) Checks and balances: Promote the separation of powers, strengthen judicial independence and preserve checks and balances.

Conclusion

It is indeed refreshing that Guyana has improved on its CPI, moving from 28 in 2012 to 40 in 2019. This was due mainly to the several key anti-corruption measures taken by the present Administration. However, enforcement poses a significant challenge due mainly to weak and inadequate institutional capacity as well as insufficient funding for the key agencies involved.

The task of any new Administration formed after the conclusion of the 2 March 2020 elections, must be to ensure effective implementation of the various anti-corruption measures through to the provision of adequate resources and strengthening institutional capacity. The failure to do so would be seen as providing lukewarm support for these measures to appease the international community of its commitment to fighting corruption.