Transparency International

Last Thursday, Transparency International (TI) issued its Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2020. Based on surveys carried out of knowledgeable businesspersons and country experts on the perceived level of corruption in the public sector, the CPI was compiled using 13 different data sources from 12 different institutions. For a country to be included, there must be a minimum of three data sources that respond to specific questions relating to:

(a) Bribery;

(b) Diversion of public funds;

(c) Prevalence of officials using public office for private gain without facing consequences;

(d) Ability of governments to contain corruption and enforce effective integrity mechanisms in the public sector;

(e) Red tape and excessive bureaucratic burden which may increase opportunities for corruption;

(f) Meritocratic versus nepotistic appointments in the civil service;

(g) Effectiveness of criminal prosecution for corrupt officials;

(h) Adequacy of laws on financial disclosure and conflict of interest prevention for public officials;

(i) Legal protection for whistleblowers, journalists and investigators when they are reporting cases of bribery and corruption;

(j) State capture by narrow vested interests; and

(k) Access of civil society to information on public affairs.

The 2020 CPI results

Most of the 180 countries surveyed have shown little or no progress in almost a decade to bring about improvements in their CPI scores. Two-thirds have scored below 50, with an average score of just 43. TI’s analysis shows that corruption not only undermines the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic but also contributes to a continuing crisis of democracy:

The emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic revealed enormous cracks in health systems and democratic institutions, underscoring that those in power or who hold government purse strings often serve their own interests instead of those most vulnerable. As the global community transitions from crisis to recovery, anticorruption efforts must keep pace to ensure a fair and just revival.

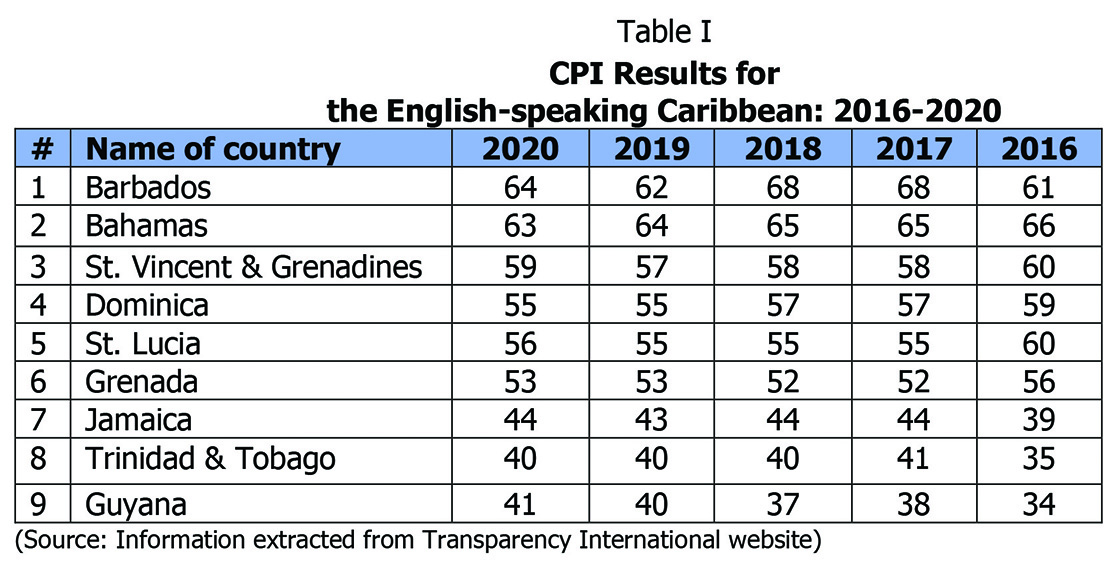

The countries that continue to score well on a scale of 0 to 100 are: New Zealand (88), Denmark (88), Finland (85), Switzerland (85), Sweden (85), Norway (84), Netherlands (82), Luxembourg (80), Canada (77), United Kingdom (77) and Australia (77). On the other hand, countries that scored poorly are: Somalia (12), South Sudan (12), Syria (14), Yemen (15), Venezuela (15), Equatorial Guinea (16), Libya (17) and North Korea (18).

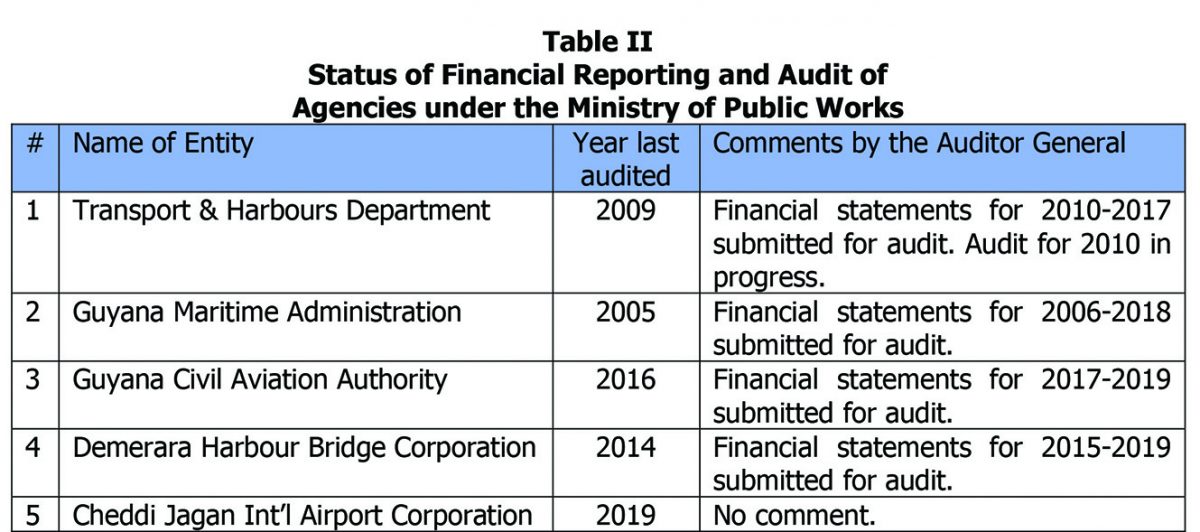

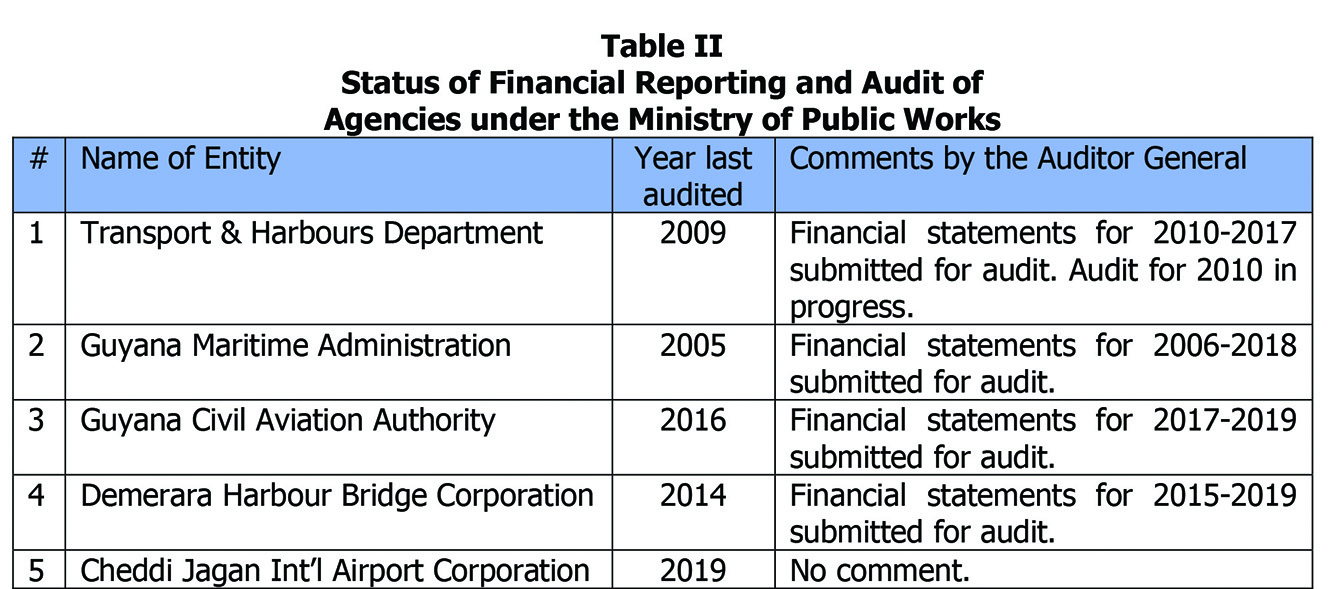

For the English-speaking Caribbean, Barbados and The Bahamas continue to top the list with scores of 64 and 63, respectively. Guyana received a score of 41 out of 100 and a ranking of 83, a one point percentage increase over its 2019 score. It has overtaken Trinidad and Tobago which is now at the bottom of the table, as shown at Table I:

TI’s recommendations

TI has made the following recommendations to assist countries in improving on their scores and ranking on the CPI:

Strengthen of oversight institutions: The COVID-19 response has exposed weaknesses and inadequacy in transparency and oversight arrangements. In this regard, anti-corruption agencies and oversight bodies must be provided with adequate funding, resources and the level of independence needed to effectively discharge their mandates. This is particularly so to ensure resources reach those most in need and are not subject to theft by the corrupt.

Ensure open and transparent contracting: Many governments have drastically relaxed procurement processes, resulting in rushed and opaque procedures that provide ample opportunities for corruption and the diversion of public resources. Contracting processes must remain open and transparent to combat wrongdoing, identify conflicts of interest and ensure fair pricing.

Defend democracy and promoting civil space: The COVID-19 crisis exacerbated democratic decline, with some governments exploiting the pandemic to suspend parliaments, renounce public accountability mechanisms, and incite violence against dissidents. To defend civic space, civil society groups and the media must have the enabling conditions to hold governments accountable.

Publish relevant data and guaranteeing access: The publication of disaggregated data on spending and distribution of resources is particularly relevant in emergency situations, to ensure fair and equitable policy responses. Governments should also ensure people receive easy, accessible, timely and meaningful information by guaranteeing their right to access information.

Strengthening of oversight institutions

In Guyana, the anti-corruption and oversight bodies are the Integrity Commission, the State Assets Recovery Agency (SARA), the Public Procurement Commission, the Audit Office, and the Public Accounts Committee (PAC).

Integrity Commission and SARA

Successive administrations have failed to live up to their obligations to deal condignly with corruption, paying lip service to the two international conventions for which Guyana is a signatory – Inter-American Convention Against Corruption and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption. The Integrity Commission, which was established by legislation 24 years ago in consequence of the former, has had a checkered history in its functioning and is currently starved of resources to enable it to effectively discharge its mandate. SARA also appeared to be non-functional, and its effectiveness left much to be desired. It has since been dismantled by the new government.

Public Procurement Commission

The Public Procurement Commission is responsible for ensuring that the procurement goods/services and the execution of works is conducted in a ‘fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost effective manner’. It is required to monitor compliance with the Procurement Act. However, after 15 years since the Constitution was amended to provide for the establishment of the Commission, it was not until 2016 that the five members of the Commission were appointed. Additionally, since October 2019, the Commission has been without the services of three of its five members because their tenure of appointment came to an end, without any replacement. The tenure of office of the remaining two members ended in October 2020.

The Procurement Act regulates the procurement of goods/services and the execution of works in order to promote competition among suppliers and contractors as well as fairness and transparency in the procurement process. However, successive reports of the Auditor General have highlighted significant breaches in the Act such as failure to adhere to the tendering process; contract-splitting; and lack of effective monitoring and supervision, resulting in short-delivery of goods/services and overpayments to contractors. Why are these breaches allowed to take place year after year without evidence of any sanctions being imposed on defaulting government officials and suppliers/contractors?

Audit Office

While the Audit Office has been timely in producing audited public accounts, the quality and comprehensiveness of the results have left much to be desired. That apart, the focus has been mainly on central government activities, considering that the public accounts also include local government bodies and all entities in which controlling interest vests in the State. Many of these entities are perhaps in greater need of scrutiny, for which significant amounts of backlogged accounts are in the possession in the Audit Office awaiting to be audited. For example, in his 2019 report, the Auditor General reported on the status of the five entities under the Ministry of Public Works that have made news in relation to purchasing gifts for government officials, as per Table II.

It would be of interest to the public if the Auditor General were to publish the list of entities his office is required to audit and the status of these audits, including the accounts in the Audit Office’s possession awaiting to be audit, and for how long.

A disturbing aspect of the Audit Office’s work is that the Auditor General is being asked to undertake ‘forensic’ audits of areas that he had already certified and pronounced on. Two examples will suffice – fees paid for legal services at the Ministry of Legal Affairs; and the expenditure on the overhead overpasses on the East Bank Demerara. He is also asked to undertake a similar assignment at the Georgetown City Council when his office has in its possession years of backlogged accounts of the Council still to be audited.

The Auditor General walks a thin line and has to be careful when asked to undertake assignments that have political motives, and not to jump at any request made. One recalls the request from the Cabinet in early 2016 for his office to undertake a transaction audit of the National Industrial and Commercial Investments Ltd. Five years on, the Auditor General is yet to honour this request. The Audit Office needs to focus on the significant amount of backlogged accounts in its possession, instead of playing to the gallery and pandering to wishes of the politicians.

The Public Accounts Committee

The PAC is responsible for examining the accounts showing the appropriation of the sums granted by the Assembly to meet public expenditure and ‘such other accounts laid before the Assembly as the Assembly may refer to the Committee together with the Auditor General’s report thereon’. Its last report was in respect of 2012-2014 and was issued in July 2017, some five years later in respect of 2012. The PAC is currently examining the public accounts for the year 2016, the results of which will be reflected in a combined report for 2015-2016.

The other accounts that are required to be laid in the Assembly are the accounts of public corporations and other entities in which controlling interest vests in the State as well as those of other statutory bodies. Section 80 of the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act requires these bodies to submit annual reports (including their audited accounts) within four months of the close of the financial year to the concerned Ministers; and for these Ministers to present them to the Assembly within two months of their receipt. However, more often than not, there has been no-compliance with these requirements. Additionally, although the accounts of many of these bodies are in need of greater scrutiny by the PAC, they are not referred to the Committee for such scrutiny. It is hoped that the current PAC will insist on compliance with the above requirement and begin its examination of these accounts.

Throughout the entire post-Independence period, the effectiveness of the work of the PAC has been adversely affected by the lack of timeliness of its examination and reporting. This has resulted in not only a build-up of backlogged accounts to be examined but also the findings and recommendations of the Auditor General repeating themselves in successive reports. Our analysis has shown that for the years 1992-2014, it took on average three and one-half years after the issuance of the Auditor General’s report, for the PAC to complete its examination and reporting back to the Assembly. Does this not explain why the findings of the Auditor General keep repeating year after year?

Unless the PAC can expedite its examination of, and reporting on, the public accounts, its work will remain an academic exercise, and the findings of the Auditor General will keep repeating themselves year after year. A fundamental principle in public financial management is the timeliness in not only financial reporting and audit but also the legislative scrutiny of results and the action is taken to remedy the deficiencies highlighted. Indeed, public accountability delayed is public accountability denied!

To be continued –