Corruption is like a balloon that is just getting bigger and bigger and bigger. We have seen situations where a Government is in office. They come in poor like a church rat. Some of them don’t want to come out of office but when they do, they want to go out as multi-billionaires because they believe that they are entitled to public monies and to the good life. And God alone knows what they wouldn’t do for it.

Prime Minister of Trinidad & Tobago, Dr. Keith Rowley

Introduction

Corruption is as old as humankind. No country is immune from it, be it a developed country or an underdeveloped one, a rich country or a poor one. Corruption is an immoral and unethical act committed by politicians and bureaucrats for their personal gain and at the expense of the broader interest. Corruption disproportionately hurts the poor, the disadvantaged and other the vulnerable groups, including the unemployed, the sick and the elderly. It results in the misallocation of scarce resources, and areas that are in genuine need of developmental assistance are overlooked in preference to programmes and activities that offer the greatest rewards to the corrupt.

High levels of corruption result in not only a distortion of trade but also goods and services becoming more costly, thereby adversely impacting on the quality and standard of living of citizens, especially middle- and low-income and other vulnerable groups. Research has shown that the corrupt politician tends to target major infrastructure works where there are large one-off payments and fewer officials involved, thereby rendering the risk of exposure is less. Corrupt governments also tend to contract high levels of long-term public debt.

Measuring corruption

Given the opaque nature of corruption, it is extremely difficult to measure actual levels of corruption in a society. An alternative therefore had to be found that is generally acceptable, with the primary intention of creating an awareness of the adverse effects of corruption and providing a basis for actions to be taken to bring about an improvement. It is against this background that the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPT) was developed. The Index is calculated based on surveys carried out of the perceptions of knowledgeable people, such as senior businessmen and political country analysts, of perceived levels of corruption in a country. The results, when computed using statistical methods, correlate well and provide some confidence about the actual levels of corruption.

Most of the countries surveyed consider the CPI as an authoritative pronouncement of what is perhaps the best substitute measure for the actual levels of corruption in their countries. Countries that share a deep concern for good governance, transparency and accountability, view the index as an important measure in their fight against corruption. An improvement in a country’s CPI score as well as its ranking is considered an indicator of a reduction in the level of corruption. The first step in the fight against corruption therefore must be the acknowledgement of the existence of corruption and the extent to which it is perceived to exist. The failure to do so will only serve to embolden those who are bent on indulging in corrupt behaviour, thereby perpetuating this immoral and unethical conduct that enriches the few at the expense of the vast majority of the citizens. In this regard, political leaders must set the tone at the top by striving to lead by example and taking condign action against those found guilty of the abuse and misuse of public office for personal gain.

The Corruption Perceptions Index 2021

On 25 January 2022, Transparency International (TI) issued its CPI for 2021. Initial reaction from around the world was generally positive, with several countries welcoming the results and pledging to take appropriate actions to bring about improvements in their performance on the Index. However, a few countries, especially those whose governments came to power with a strong anti-corruption agenda, sought to trivialize the Index when their scores and rankings have declined. According to TI, ‘[d]enial, refusing to engage with evidence that is not produced by the government itself, insisting that corruption has already been eradicated or simply blaming others will not help in the fight against corruption’.

Another concern expressed is that the Index did not fully take into account recent events. TI acknowledges this and explained that ‘data sources often take time to catch up to real-life experiences and situations. Corrupt activity not within the timeframe of this year’s Index could take a year or more to affect the scores of a country’. TI also referred to other types of studies it undertakes which are meant to complement the CPI, such as the Global Corruption Barometer that focuses on the experiences of ordinary people in dealing with corruption as they go about their daily lives.

For the 2021 CPI, 180 countries were surveyed using data gathered from 13 sources by 12 different institutions, such as the Economic Intelligence Unit, World Bank, World Economic Forum and Varieties of Democracy. For a country to be included in the Index, there must be a minimum of three data sources that respond to specific questions relating to the following:

Bribery;

Diversion of public funds;

Use of public office for private gain without facing

consequences;

Ability of governments to contain corruption and enforce effective integrity mechanisms in the public sector;

Red tape and excessive bureaucratic burden which may increase opportunities for corruption;

Meritocratic versus nepotistic appointments in government;

Effectiveness of criminal prosecution for corrupt officials;

Adequacy of laws on financial disclosure and conflict of interest prevention for public officials;

Legal protection for whistleblowers, journalists and investigators when they are reporting cases of bribery and corruption;

State capture by narrow vested interests; and

Access of civil society to information on public affairs.

The 2021 CPI results globally

About 86 percent of the 180 countries surveyed did not make any significant progress in the last decade to bring about improvements in their CPI scores, of which 131 countries were evaluated as not having made any progress at all. Two-thirds continued to score below 50, while the global average remained at 43 for the tenth year in a row. Additionally, 23 countries have significantly declined while 27 countries have recorded their lowest score ever. These statistics indicate that corruption remains a serious problem worldwide. According to TI, the analysis shows that: protecting human rights is crucial in the fight against corruption; countries with well-protected civil liberties generally score higher on the CPI, while countries who violate civil liberties tend to score lower; and the COVID-19 global pandemic has been used by many countries to curtain basic freedoms and to side-step important checks and balances.

Daniel Eriksson, CEO of TI, argues that ‘[i]n authoritarian contexts where control rests with a few, social movements are the last remaining check on power. It is the collective power held by ordinary people from all walks of life that will ultimately deliver accountability’. Delia Ferreira Rubio, Chair of TI, added her voice:

Human rights are not simply a nice-to-have in the fight against corruption. Authoritarianism makes anti-corruption efforts dependent on the whims of an elite. Ensuring that civil society and the media can speak freely and hold power to account is the only sustainable route to a corruption-free society.

The countries that continue to score well on a scale of 0 to 100 are: New Zealand (88), Denmark (88), Finland (88), Sweden (85), Norway (85), Singapore (85), Switzerland (84), Netherlands (82), Luxembourg (81), Germany (80), United Kingdom (78), Hong Kong (76), Canada (74) and Australia (73). On the other hand, countries that scored poorly are: South Sudan (11), Somalia (13), Syria (13), Venezuela (14), Yemen (16), North Korea (16), Equatorial Guinea (17) and Libya (17).

CPI results for the English-speaking Caribbean

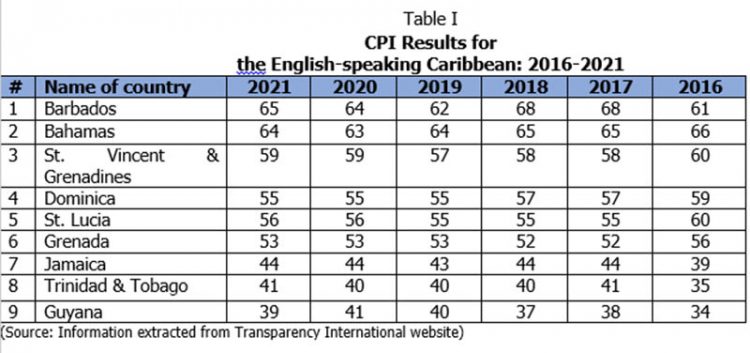

For the English-speaking Caribbean, Barbados and The Bahamas continue to top the list with scores of 65 and 64, respectively, with Guyana and Trinidad & Tobago jostling for the bottom place, scoring 39 and 41, respectively, as shown at Table I.

Acknowledging that corruption remains a serious problem for Trinidad & Tobago, the Government recently tabled legislature in Parliament on whistleblower protection. In Guyana, the Protected Disclosures Act was passed in January 2018 ‘to combat corruption and other wrongdoings by encouraging and facilitating disclosures of improper conduct in the public and private sectors, to protect persons making those disclosures from detrimental action…’. Regrettably, the Act is yet to be brought into effect. As a result, the Protected Disclosures Commission responsible for receiving and investigating disclosure of improper conduct is yet to be established.

In 2012, Guyana’s CPI score was 28 out of 100. Eight years later, it moved to 41. This 13-point increase occurred mainly during the period 2016-2020 when its score increased from 29 to 41. The largest increase was in 2016 when Guyana scored a five-point increase, moving from 29 to 34. This enhanced performance was mainly due mainly to the following:

Amendments to Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML-CFT) Act;

Conduct of numerous forensic audits of State institutions, and the involvement of Special Organised Crime Unit (SOCU) in instituting charges against certain officials;

Establishment of the now disbanded State Assets Recovery Agency (SARA);

Activation of the Public Procurement Commission (PPC);.

Appointment of new members of the Integrity Commission and the revision of the Code of Conduct contained in the Integrity Commission Act;

Establishment of Guyana’s Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative; and

Passing of whistleblower protection legislation.

In a previous article, we had stated that Guyana had the opportunity to build on this improved performance if it could continue to intensify its efforts to improve its governance, including transparency and accountability, and ensure appropriate disciplinary actions are taken against those found guilty of undermining such efforts. In this regard, we had estimated that within five years it would have been able to achieve the 50 percent mark on the CPI. Regrettably, events since the 21 December 2018 have marred such efforts, although both the 2020 and 2021 CPI did not appear to have taken these into account. Once again, Guyana has been relegated to the bottom of the table of English-speaking Caribbean countries, a position that it held since 2005 when it was first assessed, except for 2020 when it overtook the twin island republic by one percentage point.

The AML-CFT Act was amended to address the deficiencies identified by the Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF) in its third evaluation report of July 2011 and to avoid the possibility of the country being blacklisted. Prior to the May 2015 elections, there was intense political wrangling over the extent of such amendments. As regards the PPC, it took 15 years for the Commission to be activated through the appointment of the five commissioners in October 2016. Their tenure of appointment expired in October 2020. Since then, there have been no new appointments.

After 12 years’ hiatus, new commissioners for the Integrity Commission were appointed in 2018. Their tenure of office expired in February 2020. Since then, there have been no new appointments. The Commission, however, needs to go beyond monitoring the submission of annual financial returns, and carry out the more critical task of comprehensively reviewing the annual declarations of public officials to ensure there is no mismatch with their observable lifestyles. Additionally, Guyana needs to follow the example of Jamaica by merging the functions of the Integrity Commission and the Public Procurement Commission into a single anti-corruption agency. This will provide a more effective mechanism for promoting and enhancing standards of ethical conduct as well as for preventing, detecting, investigating and prosecuting acts of corruption.

TI’s recommendations

TI has made the following recommendations to assist countries in improving on their scores and ranking on the CPI:

Uphold the rights needed to hold power to account: Governments should roll back any disproportionate restrictions on freedoms of expression, association and assembly introduced since the onset of the pandemic. They should ensure justice for crimes against human rights defenders are given urgent priority;

Restore and strengthen institutional checks on power: Public oversight bodies such as anti-corruption agencies and supreme audit institutions need to be independent, well-resourced and empowered to detect and sanction wrongdoing. Parliaments and the courts should also be vigilant in preventing executive overreach;

Combat transnational corruption: Governments in advanced economies need to fix the systemic weaknesses that allow cross-border corruption to go undetected or unsanctioned. They must close legal loopholes, regulate professional enablers of financial crime, and ensure that the corrupt and their accomplices cannot escape justice; and

Uphold the right to information on government: As part of their COVID-19 recovery efforts, governments must make good on their pledge contained in the June 2021 United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Corruption (UNGASS) political declaration to include anti-corruption safeguards in public procurement. Maximum transparency in public spending protects lives and livelihoods.