By Claudia Tomlinson

Abstract

Many notable individuals of African-Caribbean descent became activists for racial justice in Britain following migration in the 1940s and 1950s. This article looks at the couples from British Guiana who formed marriage, economic, and political partnerships either prior to, or after migration to Britain, and leveraged their relationships to make powerful and enduring contributions in the fight for racial equality in the Mother Country. The partnerships explored are Jessica and Eric Huntley, the political activists who were part of founding the movement for colonial freedom from the 1940s in British Guiana, and who, following migration to Britain, were prominent activists on behalf of other black people in Britain. They became the founders of one of the leading organisations in the fight for black liberation, Bogle L’Ouverture Publications. Pansy and Lionel Jeffrey were leading community activists and Pansy founded the first club for Caribbean elders in Britain. Sybil and Joseph Phoenix were fashion entrepreneurs as well as charity activists and Sybil was at the forefront of the resistance movement following the New Cross Fire. Waveney and husband Len Bushell were activists in a number of areas in racial justice campaigns in Britain. Waveney was at the forefront of resistance against the oppression of black children in the British education system and Len was active in independence campaigns on behalf of British Guiana. Elouise and Beresford Edwards were based in the north of England and were leading activists for race equality. Beresford made headlines in the 1960s when he sued and won a famous case against a leading and powerful trade union, and Elouise was at the forefront of many organisations working on behalf of migrants to Britain. This article will explore how these couples, often co-operating with each other, made enduring contributions to the social, economic, and political life in Britain.

Jessica and Eric Huntley

Jessica and Eric Huntley married in 1950 in British Guiana and migrated to Britain, with Eric leaving in 1956 and Jessica in 1958. Both are recognised and celebrated for their anti-colonial fight against Britain’s oppression in British Guiana, and were particularly active in this fight in the 1940s and early 1950s. They helped the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) to victory in 1953 as a multi-racial coalition of workers and professionals with a vision of unifying their country. Eric had been imprisoned for political activities in 1954, and left the country shortly after his release. Prior to emigrating, Jessica had worked in a garment factory before being sacked for political organising in the company. She worked as the Party’s Organising Secretary and also worked in a laundry next to the PPP’s office. As with the education of girls in the period, Jessica was trained in shorthand and typing.

Eric had worked in postal services since his teenage years, and following his release from political detention in British Guiana, he moved to Britain as he found himself unable to resume his career in the post office due to his political activities. On his arrival in Britain, it was his friend, Lionel Jeffrey, who helped him find lodgings and took him to the Employment Exchange to find work. This network of support, comprising friends and family members, was critically important to assist new arrivals with the process of settling in. Like many arrivals from the Caribbean, Eric had periods of unemployment, and worked in casual and short-term jobs in factories, for Standard Telephones and Cables company, and for the Post Office. He worked at Mount Pleasant Post Office sorting office in London, where mail came in centrally before it was sorted and shipped to other post offices around the country. Eric has spoken about the experience in the 1950s, working there in 1957 and how hard it was to save for his wife’s passage to Britain: ‘I worked twenty-four hours a day in order to save that money. I worked overtime. I lived at the Post Office, more or less, and a number of us did in fact because we were all in similar situations; mostly the migrants were the Postmen who worked excessive overtime’. He was eventually employed by American Life Insurance, where he worked for many years.

Jessica worked in a number of clerical roles in Britain prior to becoming a full-time publisher and owner of a bookshop, which was operated alongside her formidable programme of political and community activism. She worked for a shipping company, the Ministry of Pensions based in Haringey, London, a magazine publisher in Fleet Street and Collett’s bookshop, and a firm of solicitors in Ealing.

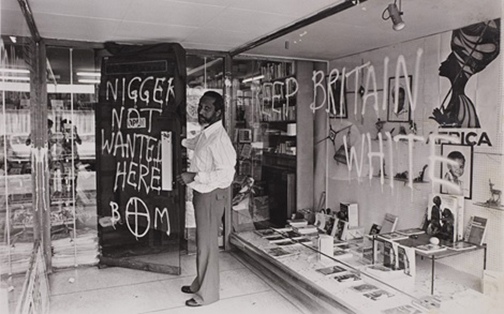

From 1968, both Jessica and Eric became company owners of Bogle L’Ouverture Publications, a publishing house established to produce publications by and for the African diaspora in London, and later Third World publications. To establish Bogle L’Ouverture Publications, Jessica Huntley raised funds from within the diaspora, and her friends from Guiana were among the main backers and supporters. It was also a base for their activism, predominantly on behalf of black people in Britain, the Caribbean, and the USA. They also opened a bookshop, which sold their publications, but also acted as a resource and cultural centre for black people, but it was also accessed by many other local people who wanted advice and assistance on a range of issues, particularly about the police and criminal justice system. Bogle L’Ouverture Publications launched the careers of many leading authors, including Walter Rodney, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Lemn Sissay, and Valerie Bloom. The bookshop came under frequent attack by racists, but the Huntleys fought back and defied threats to continue their work.

Sybil and Joseph Phoenix

An example of co-operation and collaboration between the couples being discussed was the friendship and partnership between the Huntleys and their friends Sybil and Joseph Phoenix. As business partners, the Huntleys assisted with the establishment of Phoenix Afro-European Fashions, known as ‘Phoenix Fashions,’ in London. In 1968, Eric Huntley served as Publicity Officer to assist with its launch and its inaugural fashion show. Jessica Huntley and her second son, Chauncey Huntley, assisted in modelling some of the collections in the fashion show. Phoenix Fashions was established as a successful company and held fashion shows across London.

Sybil Phoenix was born in 1927 in Georgetown, British Guiana, and worked as a seamstress upon leaving school. With exceptional skill and business acumen, she established her own business in British Guiana, Sunset Sports Wear and Leather Goods, for which she designed and sold clothing and handbags.

She married Joseph ‘Joe’ Phoenix, who was working in a bookshop in British Guiana and they became engaged there before getting married in Britain in 1958. Joseph worked in London for J. Lyons, an ice-cream maker, as Mixing Supervisor. After leaving that job, he trained as a social worker, but then moved to work in the family businesses and charities with his wife as his business partner. As entrepreneurs from a working background, Sybil and Joe Phoenix were in a position to fund other upcoming businesses, and provided financial backing to help establish Bogle L’Ouverture Publications in 1968. They also hosted fundraising events, and donated the proceeds to their favourite causes. One of the Phoenix’s favoured charities was Georgetown Hospital, for which the family regularly raised and donated funds for many years.

Sybil’s long life and career in Britain encompassed significant charitable work, fostering numerous black children in the care system, and setting up a black youth club, the Moonshot, which was burnt down by a racist organisation, but which she re-built within four years. She collaborated and co-operated with others to fight racial injustice in Britain and was one of those leading the resistance movement in the aftermath of the New Cross Fire, in which 13 black children died in a suspicious fire that was followed by an inadequate and indifferent police investigation. She participated in the Black People’s Day of Action, in which black people mobilised to march across London. She was the recipient of many awards and prizes, including the OBE.

Pansy and Lionel Jeffrey

Lionel and Pansy Jeffrey were one of the more established couples of their generation in Britain as they arrived in the mid-1940s, more than ten years before many who subsequently became part of their peer group of activists. They married in 1951.

Lionel ‘Jeff’ Jeffrey was born in 1926 and was one of the earliest of his generation to travel to Britain in 1947 to study at Oxford University. He was elected to senior roles in student union movements, and terminated his stay in Britain in 1953 when British troops arrived in British Guiana to overthrow the newly elected government. He returned home and took over the role of Secretary of the People’s Progressive Party following the imprisonment of Janet Jagan, but eventually returned to Britain in 1956. There he became actively involved in anti-colonial activism and collaborated with other leading activists, such as Pansy Jeffrey, Billy Strachan, Cleston Taylor, the Huntleys, John La Rose, Peter Blackman, Cleston Taylor, and Irma La Rose. He devoted many years to the forefront of the fight for race equality in Britain, as an advisor for Islington Council, and the Inner London Education Authority.

Pansy Jeffrey was born in 1926 in Berbice in British Guiana, and in 1946 travelled to Britain, where she trained as a nurse, midwife and health visitor. Pansy was politically active since her youth in British Guiana, attending Town Hall meetings, with a particular concern for improving child poverty and welfare. Pansy also supported Jaganism and collaborated with Cheddi and Janet Jagan’s PPP. She was appointed to the position of ‘West Indian Social Worker’ in 1959 in North Kensington, the area of the Notting Hill Riots, and where the murder of Antiguan carpenter Kelso Cochrane occurred. Her role was part of the response these events, and she served in a number of organisations and charities over many years. Like her husband, she collaborated with peers from Guiana and other parts of the Caribbean. For example, she was co-founder, with Jessica Huntley and others, of the group Women for Development in Action to assist women of African descent in Britain and Europe experiencing poverty. Pansy’s most enduring organisation is the Pepper Pot Club, which she founded in 1981 to alleviate isolation of Caribbean elders in England through the provision of lunch and activities. Now the Pepper Pot Centre, it has been patronised by the Queen, who opened the Centre, and other members of the royal family.

As well as being political associates of the Huntleys, Lionel and Pansy were part of their social circle, and part of the circle of couples who met at each other’s homes to entertain each other with West Indian food, music and dance, to maintain the friendships and keep their culture alive. Pansy and Lionel Jeffrey donated their personal and political records to the archives of Jessica and Eric Huntley, the Huntley Collection, at the London Metropolitan Archives.

Waveney and Leonard Bushell

Waveney Bushell was born in 1928 and qualified as a teacher in British Guiana and secured work in London’s East End in a tough primary school, in the same way as other compatriots, such as Beryl Gilroy. Many teachers who arrived from the Caribbean found themselves given jobs in the toughest and most deprived areas of the country, such as London’s East End, as depicted in the film To Sir With Love. She progressed to become an Educational Psychologist (EP), and may have been the first black EP in Britain, and in delivering that role encountered and fought the systematic oppression of black children in British schools.

She was a pioneer in the establishment of Black Supplementary Education schools, usually holding lessons on Saturdays, to meet the educational needs of black children who were failing educationally in schools. The story of this battle and Waveney’s contribution has been recently depicted in the documentary Subnormal: A British Scandal. She led the way, with others such as the Huntleys, Bernard Coard, Albertina Sylvester and John La Rose, and other prominent activists from the Caribbean, in speaking out at conferences. She was a founding member of the Caribbean Education and Community Worker’s Association (CECWA), an important campaigning and resistance group fighting for race equality in Britain. She took a risk as an establishment insider, to blow the whistle on what she observed as the systematic oppression of black children in the British education system. She challenged the very basis of racist psychological theory and practice, particularly the use of culturally biased testing to label black children as subnormal. She has recently been featured in a major article in The Psychologist, the Journal of the British Psychological Society. For two to three weeks while waiting to start her teaching job she worked in bookkeeping at Lyons Corner House headquarters in Kensington. Waveney Bushell and Len Bushell also provided funds in the late 1960s to assist with the establishment of Bogle L’Ouverture publications.

Leonard ‘Len’ Bushell, (1929 – 2018) was born in Kitty, Georgetown, and after completing secondary education he worked as a civil servant. Always interested in improving life for all and eradicating social justice, Len became politically active and joined the People’s Progressive Party in its early phase. Len migrated to Britain in the 1950s and although he knew Waveney as a friend in British Guiana, they married in Britain after their migration. Despite being an experienced civil servant, Len had to accept work not reflective of his experience and worked for British Railway on night shifts, as an assistant to the electrical works. This enabled him to study and he obtained a degree in Economics. He also worked in Lyons Corner House, a company already noted for providing casual labour for many immigrants from the Caribbean during the 1950s and 1960s. Len also worked in factories, again a source of casual labour for Caribbean arrivals during this period. He eventually became a college lecturer and maintained this career until his retirement.

In Britain, Len became a founding member of the British Guiana Freedom Association and picketed Downing Street with demands for freedom for British Guiana from colonial tyranny. They were joined in this movement by the Huntleys, and other compatriots after their arrival. Archival records relating to Len Bushell’s contribution are to be found in the Labour History Archive in the People’s History Museum in Manchester, and the Institute of Commonwealth Studies Library, University of London.

Waveney Bushell survives her husband and lives in south London, Britain. Archival records relating to Waveney’s work are to the found in the Huntley collection at the London Metropolitan archives, and the George Padmore Institute in London.

Elouise and Beresford Edwards

Beresford ‘Berry’ Edwards, born in 1930 at Mackenzie in British Guiana, was educated in Georgetown, the capital city. On entering the workforce, he became a worker in lithography eventually becoming a foreman at a lithography firm in Guiana. When he left Guiana in 1960 it was to study lithography and he became a skilled and experienced printer in Britain. It was during the course of this work that he became caught up in a legal case that would contribute to changing trade unionism in Britain.

In 1967, Berry Edwards, by then an extremely skilled and experienced printer in a well-paid job, was employed in a printing firm in Manchester, in the north of England, and joined the company trade union, the Society of Graphical and Allied Trades (SOGAT). At this time, unions in Britain operated a ‘closed shop’ system whereby all employees had to be a member of the union. Edwards had a temporary membership and instructed the union in writing to deduct the subscriptions from his salary. Due to an administrative oversight, the deductions were not made, and Edwards fell into several months’ arrears, unknown to him. His union membership lapsed and as he was no longer a member, the closed shop system meant he was sacked from his job. His offer to make up the arrears were denied, and he was out of a job, six days before Christmas in 1967. The employer expressed reluctance at having to dismiss Edwards, and it was the union that was the driving force behind his dismissal. There was an element of racial injustice as four white union members, who were also in arrears with their subscriptions, had been permitted to pay the arrears whereas Edwards was denied this opportunity. Further, the union threatened to strike if Edwards was not kicked out of his job. Edwards took his case against SOGAT to court.

On 27 November in 1969 in the High Court in London, Edwards won his case against SOGAT, and was awarded just under £8,000 in damages, estimated to be approximately £140,000 in today’s currency value. The union accepted that at the time he was sacked he was still a temporary member of the union because he had signed a form authorising the union to deduct his subscriptions and it was due to an oversight of the union that he fell into arrears. During the course of the hearing, SOGAT was strongly criticised by Edwards barrister, Peter Pain: ‘The Society is a large, rich and powerful union. In the ordinary way, one would expect it to be a pillar of support to a Guyanese worker trying to establish himself in this country. But in this case, the normal position has been unhappily reversed. The union, through its members and officers in Manchester, has quite literally sought to bring about the economic destruction of Mr. Edwards’. Edward’s victory resulted in a change in British law, recognising a person’s right to work. The presiding Judge Lord Denning found that ‘where a closed shop operated, a union could not adopt a rule which would permit it to expel any member on grounds which are arbitrary or capricious. Such a rule would be contrary to public policy, as being an unwarranted encroachment on a man’s right to work’. Following his dismissal, Edwards for a long period was only able to secure low paid labouring work, for which he earned a fraction of his previous salary. The damages were calculated on the projection of ten years of lost salary for Edwards.

For the remainder of his time in Britain, Edwards worked on a number of campaigns as part of the long fight against racial oppression in Britain directed at black people. He was a member of the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, the coalition of all racialised immigrants in the UK, established by Martin Luther King’s visit to the UK in 1964. He was a youth worker, and established a Black Supplementary school, and set up Manchester’s first bookshop specialising in African Caribbean literature, the African Caribbean Centre.

Beresford Edwards married Elouise Edwards, MBE, in British Guiana in 1955 and their eldest child was born in 1958. Elouise joined Beresford in Britain in 1961. Elouise was born in 1932 in Georgetown. Couples were able to leverage their economic power from the fact that when one wasn’t working, there was increased opportunity for financial support for the family as there was a second person to work. This was the case with the Edwards, and it was Elouise who provided for the family with four sons when she worked in the canteen at Manchester University, then a large hotel in Manchester. Many of her work associates were exploited workers who had emigrated to Britain and she became an advisor to them, and the Edwards home was a calling place for those in need of advice, support and assistance. She was a co-founder of the West Indian Organisations Coordinating Committee that helped black people with employment, education, accommodation, legal affairs and other matters. For example, they kept a registry of employers who would employ black people and landlords who would rent them rooms at the time of a strong colour bar.

In 1977, she also co-founded the Manchester Black Women’s Mutual Aid, which worked to provide educational advice and support to disadvantaged children. She also co-founded the Manchester Sickle Cell & Thalassaemia Centre to bring attention to conditions predominantly affecting black people in Britain and for which there were poor health and social care services. In 1994, Elouise was awarded the MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) for her services to the community. She and Beresford were also honoured by the communities they served, becoming Mama Elouise and Nana Bonsu, respectively. Elouise and Beresford Edwards returned to Guyana and died there in 2003. Elouise returned to live in Guyana and died in Georgetown in 2021. The Nana Bonsu Oral History Workshop was established in Manchester to honour their legacy. Their archives are available at the University of Manchester and the Black Cultural Archives in London.

As the current British government is proceeding to roll back as many of the gains and protections won by this generation of fighters for racial justice, it is imperative that the scrutiny and action undertaken by these couples in Britain continue. We have seen the introduction of racist legislation, such as the Nationality and Borders Bill, which will see Black Britons who have another country in which they can claim citizenship being at greater risk of sudden and unannounced withdrawal of British Nationality if Britain deems them a threat to the country. The case of Child Q, in which teachers permitted a 15-year-old black girl to be strip-searched by police officers on school premises, as well as countless ongoing atrocities experienced by black children and youth in the British education system shows that gains are being rolled back. Lastly, the deal struck between the Conservative government and the government of Rwanda, to ship undocumented migrants to Rwanda for offshore processing, is irredeemable on many levels. An understanding of the battles of recent as well as more distant history provides many lessons to inspire future generations. Learning from the experience, activities, struggles and victories of these outstanding couples from British Guiana is invaluable for generations going forward.

Further Reading

‘The life of Mama Elouise Edwards’, The Open University, 17 July 2021, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/the-life-mama-elouise-edwards

Nana Bonsu Oral History Project: The Life of a Pan-African Community Activist in Manchester, UK, https://nanabonsu.com/

‘Mrs. Sybil Phoenix MBE, OBE, MS: a profile by Yvonne Field’, Marsha Phoenix Memorial Trust. http://www.marshaphoenix.org.uk/about/history

K.D. Ewing, ‘Judicial Control of Union Rule-Book: Expulsion of Member’, The Cambridge Law Journal, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 42, No.2, pp.207 – 209, p.207.

A Guyanese by descent and based in Britain, Claudia Tomlinson is a researcher, writer, and campaigner. She is also currently a doctoral candidate researching the life of Jessica Huntley. She would like to thank the following individuals who provided information and photographs to assist with this article: Eric Huntley, Waveney Bushell, Howard Jeffrey, Woodrow Phoenix and Tony Reeves.

This article is the basis for a featured talk at the 2022 Annual Virtual Conference of the Guyana Institute of Historical Research, which takes place from 23 to 25 June, 2022. For further details and conference Zoom link visit:

Conference Zoom address: https://morehouse.zoom.us/j/99451762400

Website address: http://hazelwoolford.wix.com/gihr