At 91, Doris Harper-Wills is still basking in the afterglow of Carifesta 72, the first ever such festival to be held in the Caribbean. Fifty years later, by her recollection and that of others who played a part in that inaugural kaleidoscope of artistry, there has never been another such festival.

Accomplished musician Marilyn Dewar, who was part of a mass choir, remembers the excitement of visiting the houses in Festival City, which were built primarily as lodgings for the visiting delegations from the 25 countries which participated in the August 1972 extravaganza. She can still have a hearty laugh at the Cubans who thought it best to strip the beds of their linen and the windows of their curtains and use that to adorn themselves for a trip to the city. The linens and curtains were made of some pretty tie-dye material, so it was understandable.

But the real reason for that first festival living on in Dewar’s memory is the fact that one night after practice, her husband David Dewar, also an accomplished musician, proposed to her.

Dudley Charles, who was one of the artists in charge of setting up the art gallery at the Bishops’ High School, believes there has not been a Carifesta that was as good as 1972’s.

“Because it was the first, it was the most powerful and profound Carifesta. No other country could ever repeat that,” Charles said in a recent interview from his United States home. “And also because we had a champion for the arts. He was a cultural person who was the enforcer in the name of [the then prime minister Forbes Burnham].”

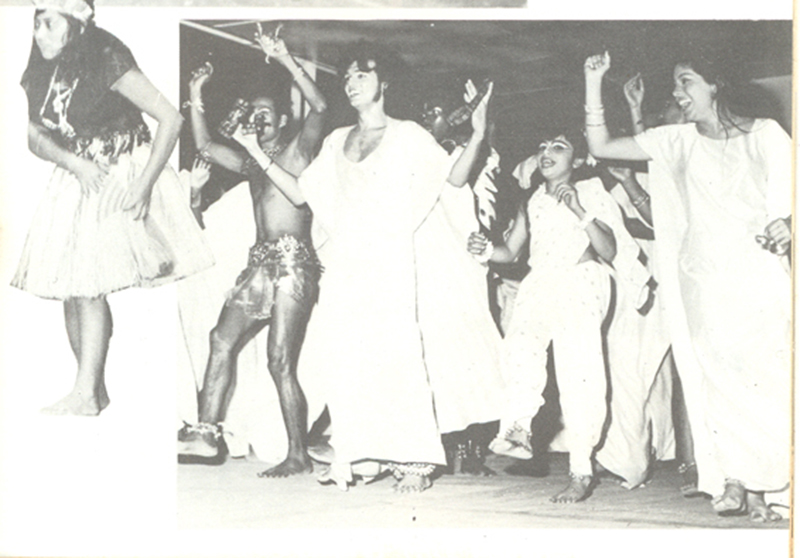

August 25, 50 years ago was the grand opening of Carifesta with input from Caribbean artists, writers, painters, sculptors, dancers and dramatists. The opening of the festival was held at the National Park as the National Cultural Centre, which was being constructed for the occasion, had not been completed. Events were still hosted there, including “The Legend of Kaieteur”, an oratorio composed by the late Philip Pilgrim, under a temporary roof consisting of tarpaulin and scaffolding.

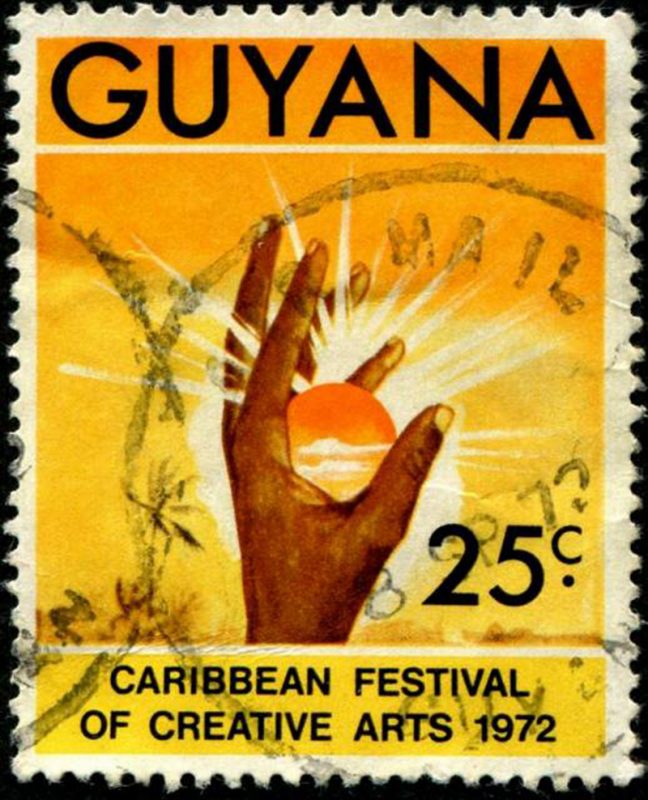

The Carifesta logo was designed by artist David Lanyi and it was of a dark hand grasping the sun depicting the skills and aspiration of a tropical people with talent.

Speaking at the virtual forum where he received the 2022 Guyana Cultural Association Lifetime Achievement Award, Lanyi recalled that the “crowd went wild” when the animated logo was revealed at intervals behind the stage as Burnham spoke. He said it took about 20 minutes for the entire logo to be revealed.

Director

Harper-Wills, who was at a restaurant in England having lunch when she was originally contacted for this interview and therefore could not accommodate it at the time, was a pageant director and choreographer at the festival.

“As an artist I enjoyed meeting other artists, especially the Brazilian Viva Bahia group,” she later recalled.

Today she still receives praise from former students, whom she said are quite famous and include Menes de Griot, Gail Nunes, and dance director Verna Walcott, all of whom live in the US, Margaret Kellman in Guyana and many others.

Harper-Wills, who now lives in England, had left Guyana when her husband was posted as ambassador to Zambia. She recalled that she attended Carifesta X as a special guest and was given much publicity. She is a performance poet, writer, dancer, dramatist, and choreographer who was born in 1931 in the village of Agricola. Over the years she has dramatised her songs and stories for international festivals in Guyana, New York (Lincoln Center and Billie Holiday Theater), London (Trafalgar Square and Covent Garden), events at the Commonwealth Institute, and British Natural History and Science Museums, as well as for BBC Radio and various television programmes.

Gwenette Kellman did not play a part in the actual art of the festival. A ‘housekeeper’, the former teacher still recalls how electrifying the excitement of the event was and she took pleasure in preparing breakfasts for the visitors. She was among a number of women who were purposely trained at the Carnegie School of Home Economics.

“I just saw the advertisement and I applied,” she shared.

She recalled that they were assigned to different houses where they prepared breakfasts for the teams and after the delegates left for their various activities, they tidied up and exited the houses until the following morning. She recalled catering for an “amazing and dramatic dancer” from Martinique who was the only participant from his country. At 78, her memories of that time live on.

The choir

Marilyn Dewar was one of 200 choir members who performed for “The Legend of Kaieteur”. They were drawn from the Woodside Choir, the Police Male Voice Choir and various churches. They rehearsed both separately and together over the weeks of preparation, at times going late into the night. As a young woman, Dewar recalled, she was very excited to be part of such an event.

It was following one of the rehearsals that David proposed to Marilyn. Laughing at the memory, she recalled how he entered her home and proposed to her in front of her shocked father. Her father, she said, was an “old time person”. David had ‘written home’ for her twice. The first time, her father gave permission for David to visit Marilyn, but he later rescinded the decision. A determined David wrote again and was successful. Next year will mark 50 years since David and Marilyn tied the knot.

Marilyn Dewar (then Hunt) was also in a play written by Frank Pilgrim for the famous Jamaican poet Louise ‘Miss Lou’ Bennett-Coverley, which chronicled her arrival in Guyana and what she was greeted with as she entered the various villages. This journey was to climax on stage, but Dewar said, “honestly between me and you the play never had an end because as fast as we were rehearsing Frank was writing and the play had no end”. She remembered that after the festival Robert Narain and Andre Sobryan put on a production at the Theatre Guild about the play that never had an end.

In 1972, Dewar’s mother was also a housekeeper in Festival City and she used to “tag along with her”, she said, so she was exposed to another aspect of the inaugural event. It was during one of those visits that they realised the visiting Cuban delegation had taken the bed linens and curtains, which were made by the Women’s Revolutionary Socialist Movement (the women’s arm of the PNC) and used them as wraps, as they had fallen in love with them.

In the night, as well, the delegations danced in the streets of Festival City to the beats of Jamaican drummer Count Ossie. “Everyday day you had something to go to,” Dewar gushed. “They used up Theatre Guild, Critchlow Labour College, everywhere. I don’t think any other Carifesta could come to that one, it was really, really great…”

Mounting exhibition

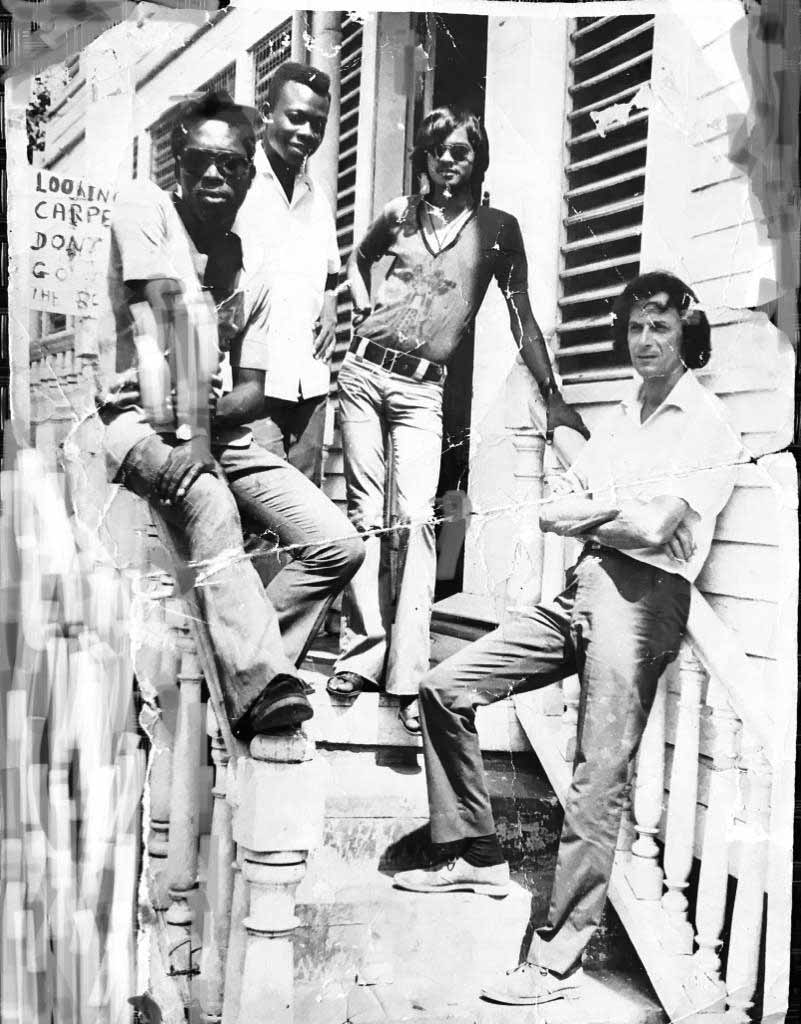

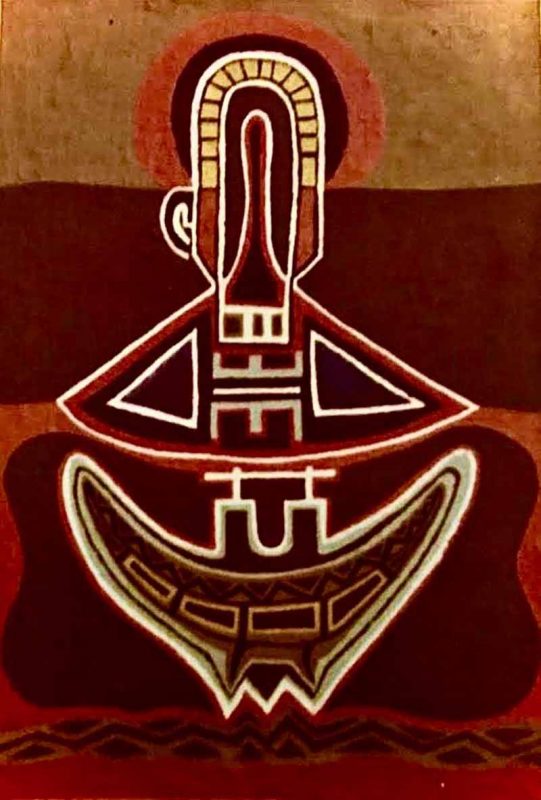

Charles was one of the artists chosen to create a gallery for all artists who were part of the festival. The building used was the Bishops’ High School, The other artists were Christie Goodheart, Zaman Ali and Cletus Henriques. According to Charles only he and Ali are still alive.

The 77-year-old said the group was given the mandate to mount the exhibition and all they were told was that countries were expected to send works of art.

They had to wait for school to be out to start preparation and the first thing they did was to remove the furniture and store them in a safe place. The interior of the school was then repainted. Crates of artwork started to arrive in the country about two weeks before the festival. It was arranged so that each country’s art was displayed in a different classroom and Charles recalled that the preparation was so arduous, they started early in the morning and worked late into the night, only to continue the cycle the next day.

“We had to make sure each piece of art sent to us was catered for,” he said.

Screens and panels were made to ensure no damage was done to the school’s interior and glass cases made to accommodate sculptures. Because Guyana had never before held such an exhibition, it was new to most of them except Henriques who had lived in Brazil and had witnessed large exhibitions.

The group of artists were thrilled to be part of history in the making and for Charles it was a success and the memory has lived on with him. He bemoaned, however, that 50 years later, Guyana still does not have a designated building for artists to mount exhibitions.

While he acknowledged that there is the Castellani House, he said there is still need for another building. Stating that visual arts has no boundary, Charles said a country should always focus on the arts.

“In Guyana there seems to be no champion to activate this part of the culture, there seems to be no appetite and I don’t know the reason why. In spite of all that, we still produce the work because it is in our nature,” the artist said.

Charles worked with the National History and Arts and later the Department of Culture. He attended the second Carifesta in Jamaica and said it was nothing compared to Guyana’s.

“I met some artists from the year before and they all said ours was better, even an artist from Jamaica said it could never be like what happened in Guyana,” he boasted.

Charles left for the US many years ago and has only returned twice, in 2004 and 2011.