Lines are ubiquitous in the natural and man-made environments. Look out your window, which itself is an arrangement of lines creating shape, you will likely see the wires of GPL and GTT. These are lines. The poles they are attached to are lines also, thick vertical lines. In the natural world, lines are everywhere. Look closely at a leaf. The veins on a leaf are lines. Even the overgrowth of grass in one’s yard can be read as lines. Depending on the type of grass the thickness of the grass will vary.

The presence and absence of line in art is perhaps as important as colour. Lines can be characterised by how they define things and how they function. In the last article, as I wrote about Alyce Cameron’s Oshun I referred to an invisible line. In fact, this was an example of an implied line. Needless to say, I did not want to jump the gun. Now that we have gotten to discussing line, I use correct art terminology to identify it. An implied line is one that is suggested and not actually present. This you may have already inferred. Implied lines are suggested by a pointing finger, a gaze, or movement of the body in space.

Similarly self-defining as an implied line, the actual line is – as the name implies – actually present. These lines can be straight, curvy, broken, continuous, diagonal, horizontal vertical…need I continue? Actual and implied lines can combine to make a line drawing in which all that is seen is communicated through lines only. No shading. In drawing a picture of a lemon attached to a stem with one leaf, the artist may draw a circle attached to a line with a leaf shape attached to it. This is an outline drawing. When the artist begins to draw the veins of the leaf the drawing ceases to be an outline drawing.

In outline drawings, the artist also does not attempt to define the form of the object by indicating areas of darkness or light. However, using the above example of the lemon, in a more worked-on line drawing the artist may do so to give an illusion of the object’s three-dimensional shape. To communicate this, the artist may use a series of parallel lines to communicate dark areas. Lines used in this manner are called hatched lines. By overlaying another series of parallel lines oriented at 90 degrees to the previous layer, the artist is able to go beyond the limits of the hatched lines. In this instance, the artist is using cross-hatching. The artist may continue to build lines in this manner to communicate areas of darkness on the form.

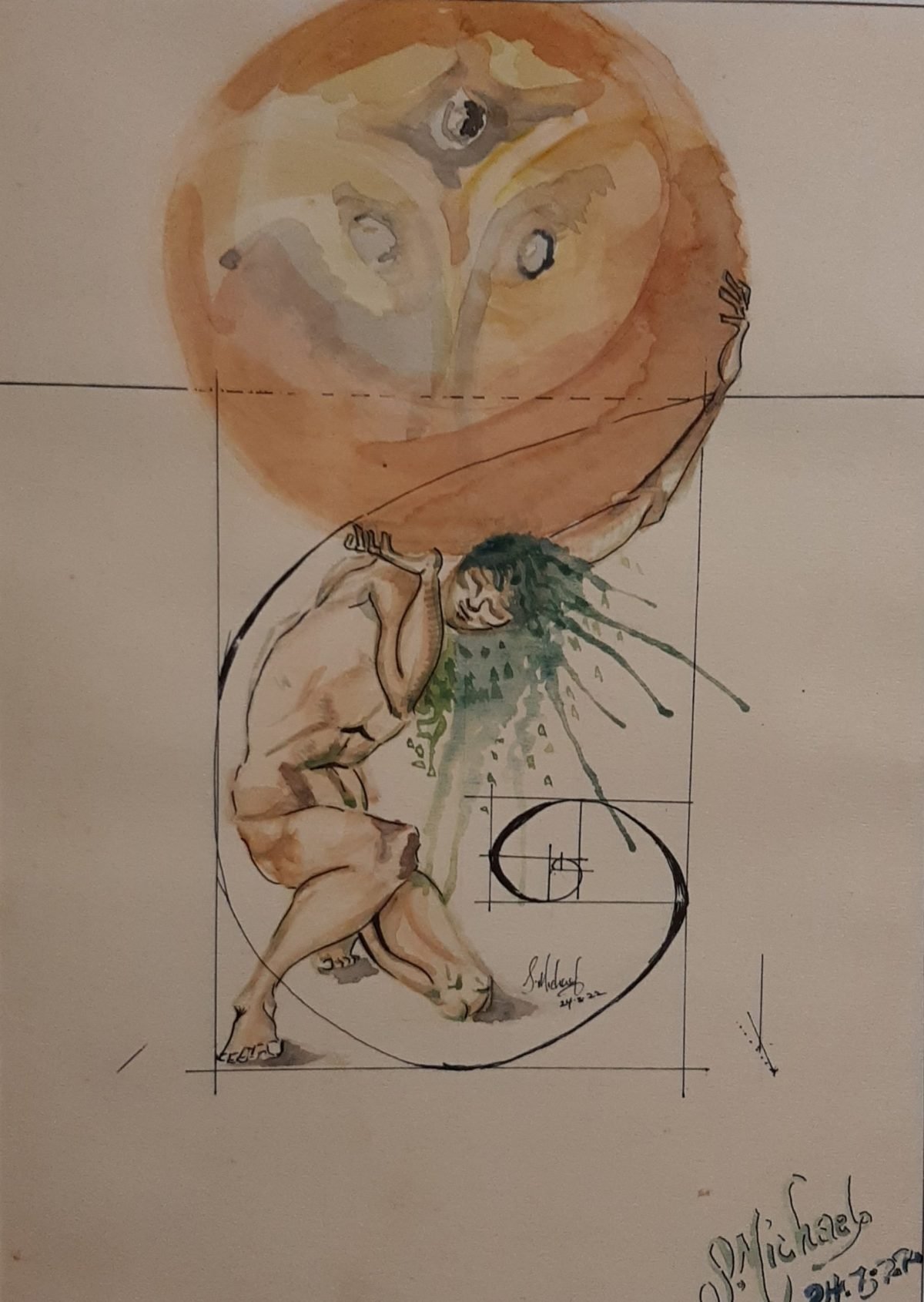

Analysing line in art is as exciting as analysing colour. Not only are lines directional – leading the eye, but they can also communicate movement, emphasis, and value. Shequita Michaels’ Coconut Spiral employs lines subtly and interestingly. The human figure of Coconut Spiral is set within an arrangement of horizontal and vertical lines. These lines converge to create geometric – rectangular – shapes. The man’s body – an organic form – is placed within the large rectangle, partially kneeling as he balances a contrasting geometric shape – a circle – on the back of his shoulders and neck. His hands extend dramatically to hold the object in place. Thus, we realise the enormity of the circular shape he holds. Without actual lines defining the boundaries of this shape, visually it reads as light and balloon-like. However, the man’s heavy-burdened posture and the extension of his left arm and the sharp angle of the right arm communicate to the viewer that appearances can be deceptive. The object is not light and balloon-like. It is not devoid of weight. The figure’s posture is filled with tension.

The tension evoked by the man’s body and the object he carries is further increased by the realisation that should he attempt to stand his body will not fit within the rectangle he crouches within. Nonetheless, the tension created by his body’s confinement in the rectangle, the object he carries, and his posture is sufficiently alleviated by the presence of gently curving lines echoed within the composition. As the eye follows the actual line of the left arm, one follows a downward line through the body that gently curves and stops at the knee on which he balances all weight. Meanwhile, a spiral line begins to unfurl in an arrangement of squares in front of his kneeling body, intersects with the right leg at the ankle, and gracefully follows the curve of his back to a point of intersection with the wrist of his left arm. This curved line gives way to a horizontal line from the point of intersection. This line is broken when it intersects with the circular shape but is otherwise continuous.

While there are other instances of beautiful lines within this work, I will not draw your attention to them. Instead, I will leave you to allow your eyes to meander around the composition to recognise the actual and implied lines and how they interact to communicate form and meaning. Additionally, we discussed colour, balance, and emphasis in the previous articles. What can you say about Michael’s Coconut Spiral in relation to colour and the principles of balance and emphasis? For instance, is the work afocal? If not, where is the focal point?

In the next article, I will return to discussing lines, and introduce shape/form, and texture.

Akima McPherson is a multi-media artist, art historian, and educator.