In this week’s edition of In Search Of West Indies Cricket Roger Seymour looks at the Test Match which the Barbadians opted not to attend.

West Indies Test cricket history is sprinkled with a potpourri of matches involving rather bizarre circumstances or unusual outcomes. There is the drawn nine-day timeless Test Match versus England, played in Jamaica in 1930; cricket’s first ever tied Test in Brisbane, Australia in 1960/61, and the dramatic one run victory, the narrowest ever at the time, in the Fourth Test at Adelaide, Australia, in 1992/93, to level the series, 1 – 1.

After our Bourda sward was converted into a lake by heavy rains in April 1976, the scheduled Third Test was switched to Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, where the visiting Indian team comfortably surpassed a daunting target of 403, to record the second highest successful run chase in history. To this list one should add the two abandoned Test matches against England; after 10.1 overs, at Sabina Park, Jamaica, in 1998; and after 10 balls at the Sir Vivian Richards Stadium, Antigua, in 2008, as both pitches were deemed unsafe for play. Not to forget the Robin Jackman affair which led to the cancellation of the 1981 Second Test against England at Bourda (The Test that never was, SN, 5 & 12/6/2016), and then there was the Boycotted Test.

In July 1991, the International Cricket Council (ICC) voted to allow South Africa to return to international cricket after 22 years, following its suspension due to the apartheid system of legislated policies of racial discrimination under a white minority government. At the time, South Africa was still negotiating its way to majority rule. Dr Ali Bacher, a former South African Test captain and a shrewd cricket administrator, who had organised the seven ‘Rebel’ tours to South Africa between 1982 and 1990 by unofficial Australian, English, West Indian and Sri Lankan teams, had emerged as the chief executive of the newly merged black and white cricket boards, the United Cricket Board of South Africa (UCBSA). The soft spoken Dr Bacher, a suave operator, had observed that the West Indies Cricket Board representative, Deryck Murray had abstain-ed on the ICC re-admission vote which led to South Africa’s participation in the 1992 World Cup in Australia and New Zealand, and he grasped the importance of having the West Indies, long the fiercest anti-apartheid crusaders, accept South Africa back in the cricketing arena. (Murray cited disagreements on the subject among the WICBC membership as the reason for the abstention.)

Bacher wasted no time in courting the West Indians. In January, WICBC President Clyde Walcott and Executive Secretary Stephen Camacho were invited to Johannesburg for a week, where, taking the bull by the horns, Bacher pressed the case for the two sides to meet. The announcement of the hastily arranged tour coincided with the World Cup clash between the teams on 5th March, in Christ-church, New Zealand, which South Africa won by 64 runs. Nelson Mandela’s written endorsement and the sanction of the relevant Caribbean governments had been secured. Jamai-can Prime Minister Michael Manley initially felt the tour was premature since South Africa still was a long way from democratic government, and only relented when Mandela supported it. (Manley resigned on 30th March, citing health reasons, before the tour began.) The brief series in the Caribbean comprised just four matches; three ODIs, one in Jamaica, two in Trinidad, and one Test match in Barbados.

The offer

Bacher had made the West Indies an offer that they could hardly refuse. The South Africans agreed to cover their own expenses, as well as the production costs of the television coverage. The tour had attracted live ball-by-ball television coverage for South Africa, Britain and throughout the Caribbean. Bacher, fully cognisant of the power of the cheque book, had secured the sponsorship of British Petroleum (BP) for his team. The WICBC, which, since the early 1970s, had losses, some heavy, during home Test series, was now looking at a potential profit.

“We felt it important that we break the ice, so to speak,” Walcott stated. “South Africa already had all the other ICC countries targeted for tours and we thought we should get playing against them providing we had the political support of the ANC which we now have.” The WICBC president also conceded that the initial agreement had been for five or six ODIs, but, “because of the television coverage, it was necessary to have something more substantial, so the Test was scheduled.” Bacher had engineered a cricketing coup, and in so doing, had gotten the WICBC to perform a 180-degree turn on its opinion of South Africa in just eight short months.

South African cricket was back on the international stage at the highest level. A Test match against the West Indies, undefeated in a Test series since 1980, undefeated at home since 1973, and undefeated at the bastion of Kensington Oval since 1935, their only loss in 28 contests, suffered on a rain-affected wicket. At that point in time the West Indies team was in transition, four sturdy pillars had just been removed; former captain Viv Richards, long-serving opener Gordon Greenidge, fast bowling genius Malcolm Marshall and tireless wicketkeeper/batsman Jeffrey Dujon. Bacher, who had led his country in their last Test series, the 4 – 0 whitewash of the Australians in 1970, must have sensed potential weakness. Whilst inflicting the worst ever thrashing upon Australia, Bacher never let up as the Proteas humiliated the visitors in four successive crushing defeats by 170 runs, an innings and 129 runs, 307 runs, and 323 runs, respectively. Next was the challenge to the West Indies on their own turf.

When the South Africans arrived in the Caribbean on 4th April, they were riding the crest of the honeymoon ‘welcome back’ wave to international cricket having shocked the world by reaching the semi-finals of the World Cup just 13 days earlier. However, Bacher’s troops were reluctant and battle-weary combatants. Their domestic cricket season runs from October to March and several players had been on the tour to India for South Africa’s first ever ODI series in November, and then participated in nine World Cup matches in February/March. The controversial semi-final loss to England, where rain briefly halted play with South Africa requiring 22 off 13 balls with four wickets in hand, later revised to an impossible 22 off one ball, was probably still foremost on their minds.

South Africa’s skipper Kepler Wessels, who had qualified to play for Australia by residency and was a veteran of 24 Tests in the Baggy Green, relayed his misgivings about the tour to Bacher, opining that “they were rushing things.” Wessels’ doubts were quickly realised when the West Indies easily dispatched the visitors in the three ODIs, by margins of 107 runs, 10 wickets and 7 wickets, respectively. Phil Simmons walloped centuries in the first and last matches to garner Man of the Match awards, while his fellow Trinidadian Brian Lara was the match winner in the second game with an unbeaten 86.

Observers expecting protesters to be at hand to question sporting links with South Africa, were instead greeted with packed houses in Jamaica and Trinidad, cheering on the home side. Surprisingly, the new West Indies captain, Richie Richardson, who was leading the team at home for the first time, was the target of hostility from a large section of the Sabina Park crowd. They booed and jeered from the moment he walked out to bat to when he was out nearly an hour later, and every time he touched the ball whilst fielding. Among the theories bandied about for the heckling of Richardson were that he was quoted as having said prior to the encounter with South Africa in the World Cup, the first ever between the two teams, that it was “just another cricket match,”; he was personally responsible for the dropping of Dujon from the World Cup squad, and he had made derogatory comments about Jamaica. Whatever the perceived slight, the heckling must have been a great source of embarrassment to both the Jamaica Cricket Board and the WICBC.

The boycott

Prior to the team’s departure from Trinidad for Barbados, the West Indies selectors announced the names of the 13-man squad for the Test match. Conspicuous by omission was the name Anderson Cummins, the Barbadian fast bowler, who had played in the final six (of eight) World Cup matches and all three ODIs versus South Africa. Cummins’s absence from the team set off a firestorm of emotion in Barbados which raged until after the match was over. All hell broke loose in the four days prior to the start of the match on Easter Saturday, 18th April, as the Barbadians raised the roof in protest. The talk of a boycott had been floated since early February, when Barbadians Carlisle Best and Philo Wallace were omitted from the World Cup squad, but had failed to materialise for the Barbados/Leeward Islands game at the Kensington Oval.

This time around, the hurricane of protest was gathering momentum, as local radio stations and newspapers – the Barbados Advocate and the Nation – focused on the perceived slight. All manner of theories were tossed into the cauldron of dissent; there was a general anti-Barbadian sentiment supported by the dropping of Best, the passing over of the senior member of the team, Desmond Haynes for the captaincy, and the critical remarks from Malcolm Marshall over his treatment during the World Cup which led to his premature retirement. Irate callers to radio call-in programmes focused on nothing else and constantly berated the selectors while the Advocate headline declared Cummins’s omission “totally outrageous.”

Well the Barbadians did ‘walk the talk’ and boycotted the Test match. Media reports on the attendance vary from 6,500 for the five days of the match to 3,000 on the first day and dwindling to 500 for the last day. Even these numbers sound a bit too generous when one peruses photographs from the match which show two or three spectators scattered across the expanse of an entire stand. The Red Stripe Caribbean Cricket Quarterly edition of July/September 1992 (Volume 2, Number 3), stated, “The boycott was almost total, from members of the George Challenor Stand to regulars in the Kensington Stand and on the grounds.” The WICBC reckoned that its losses through the gates totalled Bds$300,000., a figure that speaks for itself.

While the Barbadians stayed home (perhaps they didn’t resist the temptation to view the game on television) television viewers elsewhere were enthralled by a match in which Bacher’s troops held the upper hand for most of the first four days. After Wessels won the toss and invited the hosts to bat, Haynes and Simmons, the opening pair put on 99, at a run a minute as the West Indies looked set for a huge score. Cruising along at 226 for four at tea, the West Indies subsequently crumbled to 262 all out before the close of play. Resuming at 13 without loss, the South Africans consolidated their position on the second day, reaching 254 for four wickets, with Andrew Hudson, 135 not out, becoming the first South African to score a century on Test debut.

Just as they were looking to build a formidable lead on the third day, Richardson called on Test debutante Jimmy Adams, who replaced the injured Carl Hooper. The occasional slow left arm spinner promptly swung the tide with four wickets to restrict the visitors’ lead to 83. At the close of play, heading into the rest day, the West Indies, following a middle order collapse, were teetering on the brink with a precarious 184 for 7, with Adams (23) and fellow newcomer, Kenny

Benjamin (7), the not-out batsmen. The lead was a meagre 101.

On the fourth morning, as Adams played with a maturity belying his experience, the West Indies’ tail wagged and wagged. With the fast bowling duo of fellow Jamaicans, Adams added 25 for the ninth wicket with Courtney Walsh, and then 62 more priceless runs for the last wicket with Patrick Patterson.

Adams was undefeated on 79 as the second innings closed on 283. Bacher’s battalion had two sessions and a day to get 201, on a wicket that was starting to show signs of wear. Although Ambrose quickly removed the openers, Wessels (74) and Peter Kirsten (36) guided South Africa to 122 for 2 at the close, 79 short of victory.

South African Coach Mike Proctor, whose Test career was all of seven matches, his last series being the 1970 Australian thumping, warned his players that the match was not over yet. Proctor, who had played 13 years of county cricket for Gloucestershire was very familiar with the West Indians and knew they would make a game of it.

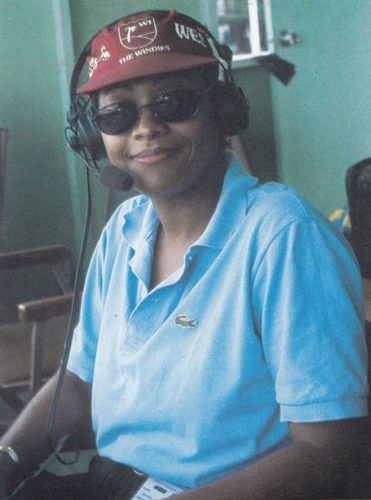

Barbadian Donna Symmonds was in the commentary booth. Here she is recalling the fifth day in an interview in the March/April 2000 edition of Caribbean Beat: “On the last day, South Africa were 122 for two, needing only 201 to win, and there was this feeling, obviously, that the West Indies would lose, and there was nobody there, just a few selectors and barmen and groundsmen and — us. And empty stands: the outside mikes were picking up: phhh. And then, the West Indies started this phenomenal comeback. Ambrose and Walsh bowled unchanged, and the match just took on a whole different aura. And yet there was no atmosphere. So you had to conjure. It was amazing. It was probably the most difficult match I’ve ever done, and yet it then turned into one of the most rewarding, because I think we did a good job of it. But, you know what was really sad at the end? After Ambrose and Walsh took the last eight wickets for 26 runs, bowling South Africa out for 148, and they [the West Indies team] did this victory lap around Kensington: there was nobody to cheer them. It was bizarre.”

Bacher’s coup had been foiled. Most Barbadians would tell you that they were there to witness it; Donna Symmonds would probably laugh.

Trivia question: Can you name the third West Indian Test debutante in this match?