Marcia Smith was a housewife when her son Jared, who is now 17, was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Today she is a special education educator and the founder of Gifted Hands Learning Centre for Special Needs.

ASD is defined as a developmental disability caused by differences in the brain. People with ASD often have problems with communication and social interaction. Autism Awareness Month is observed in April.

“In 2008, when Jared was three years, the nurse told me he has signs of being autistic. Autistic was a new word to me,” Smith said in an interview with Stabroek Weekend. “My eldest daughter was working at NCN [National Communications Network] at the time so I asked her to research the word for me. When she brought a printout, the first thing I read was there is no cure for autism. After reading that I asked myself, what am I supposed to do here now? I decided I have to help my son the best I could, cost me what it will. When you read your child may never know you, never talk, never ride a bike, I asked myself what did I do wrong? Knowing there was no cure for autism, I focused on Jared living an independent life. I had to re-educate myself.”

Reorienting; Jared

Smith signed up for a child care course at the Adult Education Association (AEA) as she sought help with the issue of raising Jared. However, no one was familiar with the word autism. Instead her lecturer asked her to share with the class what she knew of it.

She took Jared to language and speech therapy sessions at the Georgetown Public Hospital where she met a group of mothers who were told by different doctors their children were autistic. They shared their concerns, tears and laughter about their children and related issues.

“In Guyana at the time there was no full diagnosis. There were just doctors treating your children from signs and symptoms the children exhibited,” she noted.

Jared made no sound except for when he cried. “Then he started to use gestures. He never smiled. Until now he does not smile. Now and again you will hear him laughing,” she said.

Jared walked at 14 months and started saying a few words at seven years old. He attended East Street Nursery School and was then placed at Winfer Gardens Primary where the head teachers always showed interest in his progress.

“However, some days at school he wrote absolutely nothing,” Smith recounted. “Some days I took him out of classes for therapy. In grade two, a child slammed Jared’s head to the blackboard; another child pushed him down the stairs. He was bullied. Other children who knew he couldn’t say exactly what happened, told me as soon as I reached the school gate. Many days my heart ached and I cried but I was determined to help him the best way I could.”

In Grade Two, Smith asked the Ministry of Education (MoE) to consider allowing Jared to repeat. “I went through the chain of command. I met with the then Chief Education Officer (CEdO). That wasn’t a pleasant meeting, he said some of the most hurtful things to me and we exchanged words over the No Child Left Behind policy and automatic promotion. My child was promoted even though he had not learned anything from Grade Two,” she said

When Jared was in Grade Four, the government changed and Smith met with the new minister of education. The new CEdO granted permission for Jared to repeat Grade Four. “I was concerned about Jared going through the system without grasping any concepts,” she noted.

When he repeated Grade Four, one child befriended him. They are still friends. “Even when he did not finish his work, his friend, Kwame, helped him,” she said.

When he was approaching the time to write the National Grade Six Assessment (NGSA) Smith was hesitant but a friend encouraged her to give Jared a chance.

He wrote the NGSA exams. By then he was talking and making sentences. He was given a place at Freeburg Secondary, but Smith asked for him to be placed at St Barnabas Special School where he spent a year. “I knew my child’s ability. I didn’t want him to get lost again,” she said.

During the second term, Jared’s teacher told her the school was recommending that he be placed in a regular secondary school because of his aptitude; they had seen his work improving when challenged. At the end of that school year, he was placed at Kingston Secondary School (KSS).

He is now in Grade Ten at KSS and is no longer a grade C student. From a student who never got even 25 percent in primary school, by last Christmas term at KSS he got 72.3 percent overall. On Wednesday, he received the MoE Improved Academic Performance trophy for 2023.

Jared loves Maths and whenever there is a group assignment at school, Smith usually asks for him to do it alone. “Sometimes the children do not cooperate with him and he is always concerned about his grades,” she said.

When she last met with individual subject teachers on Jared’s performance, the information technology teacher said he was the only student who did the term’s course IT assignment. “He did a powerpoint presentation and she was blown away because the abled children did absolutely nothing,” Smith said.

In another assignment for agriculture, Jared completed it on his cell phone. He voiced the assignment and drew a diagram on his phone. “His teacher called me at 10 the night and asked me if I saw his assignment,” she said.

In the meantime, Jared took swimming as one of his therapies. He also had speech and language therapy and is a second dan black belt karateka.

During the last learn-to-swim exercise the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport held, Jared was an assistant swim instructor for which he earned his first pay cheque. “Jared worked through the two weeks. He was thorough,” Smith said. “One afternoon, when we were leaving the centre, he was so excited to see his former swim instructor he ran to her and gave her a big hug. He said, ‘I must say thank you. You taught me and now I am teaching’.”

With the August holidays approaching, Jared has been interviewed and is set to take part in the ministry’s work study programme. He is also preparing to write several subjects at the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate exams. “I am not sure how many subjects he wants to write. This week he will say what he wants and next week he will say another thing,” his mother said.

Smith took Jared to the US five years ago on vacation. To date he has not said how his vacation was but occasionally he sees some things on television and relate them to his vacation.

Jared also loves to cook and eat. “If push comes to shove he will help himself. He makes a fine sausage stew. He fries eggs and sausages and can cook rice,” Smith said. “Most children on the spectrum do not like to wear shirts. When you find Jared at home he is without a shirt. When he is cooking and there is a spill he says a little burn won’t kill him.”

According to Smith, some parents beat their children because they think they cannot learn. “That is due to not enough awareness or not enough acceptance of children’s disabilities and they cast blame on either parents’ sides of their families. When I had 28 students, if I had five fathers coming with the children, I had a lot,” she added.

She noted Jared has taught her much. Because of Jared, she became a member of the President’s Youth Award Republic of Guyana (PYARG) scheme and is now a PYARG unit leader.

Helping hands

Inspired by Jared, on April 16, 2012, Smith opened Gifted Hands to focus on special needs education. It is registered with the MoE as a private school and was Initially located on Parade Street, Kingston. However, on August 4, 2020, the building that housed Gifted Hands was gutted by fire.

“I lost 95 per cent of everything I accumulated from 2012 to 2020. Now we are at 192 First Street and Stone Avenue, Campbellville where I had to restart. The place is much bigger. However, when I closed in 2020 due to the pandemic, I had 28 students. When I reopened last year on February 7, I restarted with five,” she said. “To date I have 12 on the register. Two are non-verbal, seven are with Down syndrome and three are on the autism spectrum. Students are taught reading, maths and language.”

Smith works with teenagers and young adults, as the ages of those with special needs are not chronological. “Their cognitive development says it all. My eldest student turned 55 on Saturday and she behaves like a child of five or six years,” she said.

Some of her students, like the 55-year-old, have been with the centre since its opening. “It is a safe space and a place where they can socialise. Apart from the academics, we teach them life skills such as doing their own laundry and making simple meals,” she added.

The school is the beneficiary of donors from a few entities including the Mohammed family and Digicel.

For the first time, last year, her students received government’s cash grant given to school children. Smith also bought Jared a laptop with the $100,000 special grant the government gave last year to people with disabilities. “Parents have to invest in their children with special needs. It is not living in denial. It may take time to accept but it is only with acceptance you can move forward,” she noted.

Smith attended South Georgetown Secondary and the Carnegie School of Home Economics then was married. Prior to opening Gifted Hands, Smith was a stay-at-home mom with four children. “After I got married, I felt I didn’t have to work outside of the home. My world changed after hearing that Jared might never know me. I said my child will not sit and drool. My child will develop and learn. Between three and four years he was just sitting and doing nothing. After seven years he was making sentences. I encourage parents, not because your child says nothing at three years that means he or she will never speak. Jared talks so much, sometimes I have to tell him to let he and his imaginary friends be quiet,” she added.

“Jared made me go back to school and enter special education. I take every training opportunity possible to educate myself and staff in education and specifically special needs education. Whenever there is training at the National Centre for Educational Resource Development we take part. Whenever NCERD holds head teachers’ meetings, we are there.”

Children with autism are fully diagnosed by six years old. In Guyana, they are tested at the Regional Diagnostic Centre located at the Cyril Potter College of Education Campus, Turkeyen.

Depending on the children’s progress Smith recommends placements for them at other special needs schools. “It depends on their abilities, levels of development and the parents. If parents are in denial about their children’s abilities there is nothing more I can do,” she noted.

She also makes recommendations to the special needs officers attached to the MoE and also for some to be tested at Regional Diagnostic Centre.

The Ministry of Agriculture is currently assisting Gifted Hands with a shadehouse in which the students grow garden crops. “We got seedlings from NAREI [National Agricultural, Research and Extension Institute]. The first crop perished due to bad weather. Before school closed for the Easter, students took home lettuce, pak choy and mustard callaloo. We’re into a third crop… watering the plants is a part of their daily activity,” Smith said.

Children get to the school as early as 7.30 am but activities begin at 8.30 am. They do physical exercises. Reading, language and maths are done on a one-on-one basis. “I have a non-verbal student who comes for reinforcement. I liaise with the school to get an idea of the work he does. He comes from 1.00 pm to 2.30 pm,” she added.

Gifted Hands also obtained permission to use the Colgrain Pool. Due to the pandemic the pool was closed. When the centre reopened last February, permission was granted to restart.

One of Smith’s past students, Annison Forde, is a Special Olympian who secured gold, silver and bronze medals at the Special Olympics held in Orlando, Florida last year. At the Special Olympics, he was diagnosed with also being deaf and immediately outfitted with hearing aids. Smith said his achievement has to date not been recognised by those in the state’s authority. He is now a member of the Guyana Police Force.

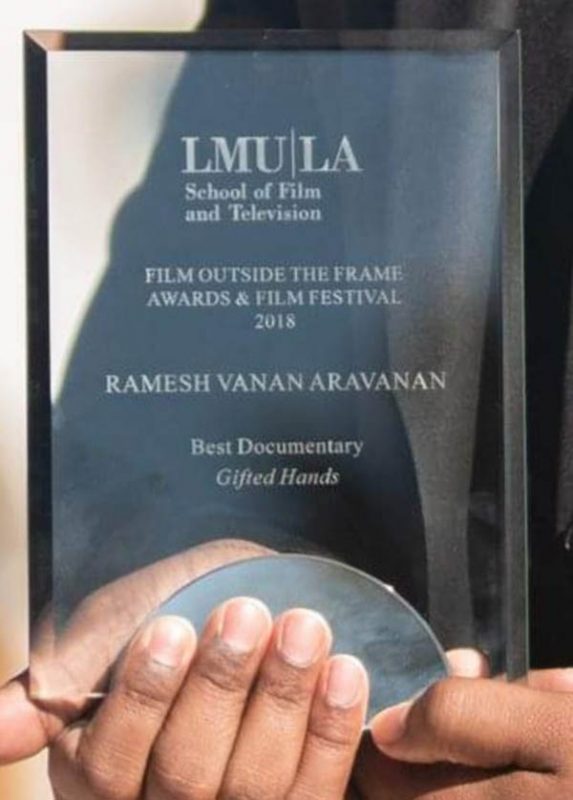

In 2016, Smith said, a Catholic priest, Fr Ramesh Vanan, was in Guyana for a brief period. He did a documentary on her, Jared and the centre, which won the best documentary award at the Loyola Marymount University’s School of Film and Television awards in the promotion of social justice category.