By Roger Seymour A reminder

In 2007, senior citizens in the Caribbean empathized with the younger generations as they anxiously awaited the release of the Patterson Report and the timetable for the implementation of its recommendations. The older folks were justifiably wary of such committees, reports and proposals. In 1938, the British Government had initiated the West India Royal Commission – also known as the Moyne Commission – following labour unrest throughout the Caribbean colonies during the period 1934-1939. The commission was given the broad mandate to “investigate social and economic conditions in Barbados, British Guiana, British Honduras, Jamaica, the Leeward Islands, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Windward Islands, and matters connected therewith, and to make recommendations.” (Moyne Report 1945)

The Moyne Commission arrived in Jamaica on 1st November, 1938, for a tour of the British West Indies, which had to be aborted five months later with the onset of World War II. The findings of the commission were so disturbing that the British Government only released a summary of its recommendations in 1940, and withheld the release of the report in its entirety until July 1945.

The Patterson Report

In mid-July, 2007, the Patterson Committee presented an interim report in the form of an aide-memoire, excerpts of which appeared in newspapers across the Caribbean under the headline, “Patterson Committee slams WICB in interim report.”

The Governance Review Committee stated that they were guided in their approach by the fact that “West Indies Cricket does not belong to the West Indies Cricket Board but to the people of the Caribbean.” It was upon this premise that they based their recommendations on how best cricket in the West Indies should be governed and how the various deficiencies might be rectified.

The Jamaica Observer of 17th July, 2007 quoted the committee thus: “West Indies cricket is in an unacceptable state and despite previous studies and reports yielding an avalanche of documents, the slide has been sharp and is continuing.”

The Observer article stated that in the wide-ranging report, the final version of which was still due, the Commissioners had noted a number of negative perceptions about West Indies, “which, whatever their validity, [they] consider it necessary to address”.

The Commissioners identified the inefficient administration of the WICB, flawed sponsorship deals, shambolic finances, and funding not reaching the territorial boards as the negative perceptions of the regional governing body, the newspaper said.

“We intend to address these concerns in advising how the WICB should be set up and run,” it quoted them as saying. “Changes are essential, and a new departure is great.”

According to the article, two recommendations for restructuring were made. The first was the replacement of the WICB with a West Indies Cricket Commission that would include all the major interest groups including the territorial boards, players, women, Caricom, among others. The second was for the WICB to be floated as a publicly-listed company on regional stock exchanges, with directors accountable to shareholders, and with an annual general meeting.

The Commissioners asserted, the article said, that no matter how the WICB was chosen, there must be a clear delineation between its role as a policy-making and monitoring entity and that of the management and staff as the executing arm.

The Final Report was duly submitted in October, 2007. In the seventh part of the review, Recommendations and Conclusion, in the second section titled, ‘The Next Steps’, the Committee laid out clearly defined steps for the transition to a modern-day governance structure.

The first seven of 12 were: “24.3 The steps [in bold print], which we now propose, are as follows:

The Board should initiate the process by approving the new structure of governance at a special meeting convened for the purpose in November.

Concurrently, we shall suggest to regional governments and other stakeholders involved to do likewise during this period.

The ground can therefore be prepared for a Special General Meeting of the Board, which will be invited to formally approve the new structure and issue drafting instructions to its legal advisors to prepare the requisite amendments to the Constitution and Articles of Association.

The Special General Meeting can agree to reconvene in one month to approve the amended documents.

On the same occasion, or shortly thereafter, the first meeting of the new Council can be held. That meeting will appoint the President, the Vice-President and other directors of the new Board.

If such a timetable can be adhered to, the new structure would have come fully into operation by 1 May 2008. By that time the new board would have met and appointed its sub-committees.

These deadlines can be met if in the months following receipt of our report, informal consultations were to take place within and between the principal stakeholder groups involved so that the ground is prepared for the series of decisions required to bring the entire system into operation by the dates indicated.”

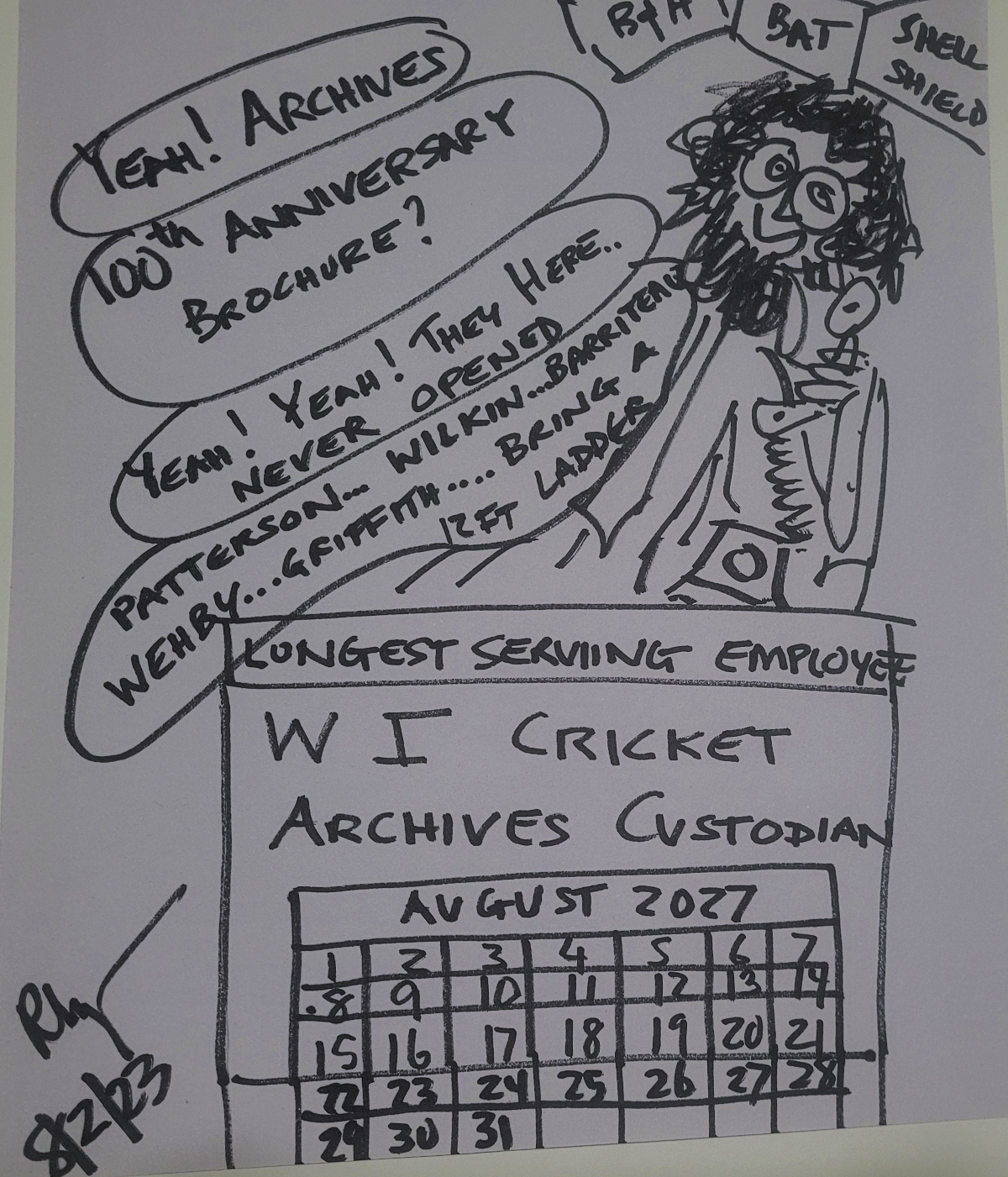

The West Indian cricketing public bubbling with anticipation for a new dawn were totally blown away by the WICB’s inertia to the report, as they continued to function without the slightest degree of urgency for the desperate need to change their way of running the game. It was as if the Governance Committee on West Indies Cricket had never existed, and the Patterson Report to all intents and purposes seemed destined to suffer the same fate as the recently exhumed Griffith Report (1992).

It was the commencement of a vicious ongoing cycle of heated verbal exchanges, more committees, more reports, more inertia, more wars of words.

Notes from the Fallout – 2008 to 2023

Charles Wilkin, a Kittian lawyer, and member of WICB Marketing Committee published an article titled “The governance of WI Cricket” in which he noted that the WICB had met in February, 2008 and considered the report.

“While some recommendations of the Governance Committee have been already implemented and a new draft strategic plan has been published since, the most significant recommendations of the Governance Committee seem to have been ignored by the Board,” the Cambridge graduate stated. Later, the former Leeward Islands captain added, “The board has not announced its response to the Governance Committee restructuring proposals nor an indication as to whether and/ or when it will respond.” (Stabroek News, 17/8/ 2008)

December 8th, 2008, WICB Blasts Patterson Report – WICB press release. WICB President Julian Hunte stated that the Patterson report had failed to address many of the major challenges facing West Indies cricket and its administration, and those addressed are outdated. “Among these issues [not addressed] are the negotiation of players’ rights, intellectual property rights of cricketers, trade negotiation, the financing of international cricket, the issue of technology and the development of players, the issue of television and internet broadcasting rights,” the statement said.

At the time Hunte was responding to a scathing four-page letter from the Patterson Committee, [which had been copied to the media], which “expressed its disappointment with the WICB’s hierarchy for its lack of interest in the report and said that after more than a year, the people of the West Indies were still in the dark as to the outcome of the WICB’s deliberations and the consequent fate of the report.”

“The governing body noted that it had accepted the Patterson Committee Report’s recommendation on the issue of a Stakeholders’ Council as an advisory council, as opposed to an authoritative council over the directors.” (Jamaica Gleaner, December 11th, 2008).

“Wanted: A new governance for West Indies cricket” – screamed the headline of an article penned by Governance Committee Chairman P J Patterson on behalf of his colleagues, published by the Jamaica Gleaner, August 24th, 2009. The battle of words resumed.

“It is erroneous to pretend or attempt to portray the notion that the West Indies Cricket Board (WICB) has accepted and is proceeding in accordance with the report submitted by Sir Alister McIntyre, Dr Ian McDonald and myself. The proper litmus test must measure the qualitative changes which have been approved and not the proportion of recommendations which have been accepted in order to determine whether or not the raison d’etre for commissioning the report has been satisfied,” the edited version of the contribution began.

“I challenge anyone to point out a single iota or even the semblance of change which has been made to the composition and structure of the WICB as a result of our report.”

Patterson later declared, “We were forewarned, in the light of previous reports which lay buried, that our efforts would bear no fruit. Little did we realise that decisions on the most vital aspects would be taken, kept secret for a considerable period and then eventually obscured under the guise that approximately 47 of our 65 recommendations had been approved.

“None of us was so beset with the sin of arrogance to believe that recommendations in our report were “edicts or directives”, but we dared to hope that the “strong suggestions” we made, grounded on a process of full consultation, would have merited careful and serious consideration in charting the path for the early recovery and future growth of West Indian cricket.

“Contrary to our expectations, we were never afforded the courtesy or the opportunity to meet with the full board for a discussion of the report and to clarify, or explain, if necessary, any portion of our report. Indeed, we learnt for the very first time in November last year that the board, without any reference to the acknowledged stakeholders in WI cricket, had decided at its meeting of February 2008 to reject completely our recommendations to alter the composition of the board and the method of its appointment.”

The lengthy challenge to the WICB concluded, “ … the inescapable conclusion that the pith of our report, as to governance, has been totally rejected and leaves untouched the kernel of a structure which even the present board admits to be outdated, unwieldy and inadequate.

“It is nearly two years since we submitted our report. It would be useful not merely to say what has been agreed, but to identify exactly what has been implemented since then.”

Years later, Patterson would publicly lament that he had wasted a year of his life serving on the governance committee.

The carousel has never stopped spinning and history continues to repeat itself. The West Indies appointed another committee in 2012, and the subsequent Charles Wilkin Report which echoed the Patterson Report was, as expected, swept under the carpet. In October 2014, there was the fiasco of the West Indians aborting their tour of India, and the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) threatening to seek compensation from the West Indies board to the tune of US$47.2 million for the losses it suffered in broadcasting rights fees, title and team sponsorship, and ticket sales. In an email to WICB president Dave Cameron, BCCI Secretary Sanjay Patel, as he had done in previous statements, laid the blame for the withdrawal squarely at Cameron’s feet and not the players. “Finally, after the fourth ODI at Dharamshala on October 17, you pulled out your team and communicated your decision to cancel the remainder of the tour,” Patel wrote.

“The adverse financial ramifications and the negative impact of your action to unilaterally cancel the remainder of the tour was well within your understanding, yet you still went ahead and cancelled the tour in complete disregard of your legal commitments.”

This crisis led to pressure for reform from Caricom, and the Barriteau Committee was jointly established by the WICB and Caricom in 2015. The Barriteau Committee’s recommendations in November 2015 echoed the sentiments of the Patterson and Wilkin reports, calling for the “immediate dissolution of the board” and a new governance structure was met once again with the sternest of rebukes by the territorial boards as an “unnecessary and intrusive demand”. Cameron accused the report of making “findings and recommendations … not supported by facts.” He claimed that it was “wrong to blame governance of the WICB for the team’s performances on the field.

At the same time, Cameron announced the formation of a panel of “experts” to assess the proposals not implemented from the earlier reports on governance. Another time wasting tactic to stay entrenched.

Three former WICB presidents – Sir Wes Hall, Patrick Rousseau and Ken Gordon – issued a joint statement on 17th November, 2015, condemning Cameron’s blunt refusal to meet with the Caricom Cricket Governance Committee following the release of the Barriteau Report.

The war of words between the West Indies Board and all comers has never stopped. No one is spared.

“We’re being told in the West Indies – and I was told to my face along with my colleague the Prime Minister of Grenada [Dr Keith Mitchell] that you (Caricom) have no say in this. This is West Indies Cricket Inc. and it is their shareholders they have to please.

“I don’t know who the shareholders are but what I do know is that unless there are drastic changes to the current arrangements, West Indies cricket will never get back where we expect it to be,” said Trinidad and Tobago Prime Minister Dr. Keith Rowley on a morning television show in Trinidad in April, 2017.

“Caribbean cricket has been hijacked by a small clique of people who are hell bent on destroying Caribbean cricket and my position [is], unless the question is answered as to who owns that asset, we’re spinning top in mud,” Rowley noted.

When Ricky Skerritt replaced Cameron as the head of Cricket West Indies (CWI) in March, 2019, he promised fatefully to deliver the long overdue change in governance structure, and immediately appointed another committee. The Wehby Report was presented in August 2020, and was immediately greeted with a vile statement by Conde Riley, Barbados Cricket Association (BCA) President and a CWI Director, that the BCA had assembled a high powered committee to perform urgent surgery on the Wehby Report.

The war of words will never cease. As long as the Camerons and the Rileys of the Caribbean manage to get themselves elected as the territorial representatives on the CWI, there will never be any change in governance. It is as simple as that.

How will this praying mantis cannibalistic copulation ritual cycle end? Wishful thinking would suggest that common sense might prevail one day and the board might opt for dissolution. Hardly likely. Perhaps one territory might develop a core group of highly talented and skilled players and opt to go on its own, as far-fetched as that might seem, eventually leading to the disintegration of the West Indies as a unit. Who knows? A hundred years from now anthropologists and historians trying to figure out whatever became of the game of cricket in the Caribbean can begin with the Patterson Report and the subsequent fallout after its presentation. It’s a sad requiem to West Indies cricket.