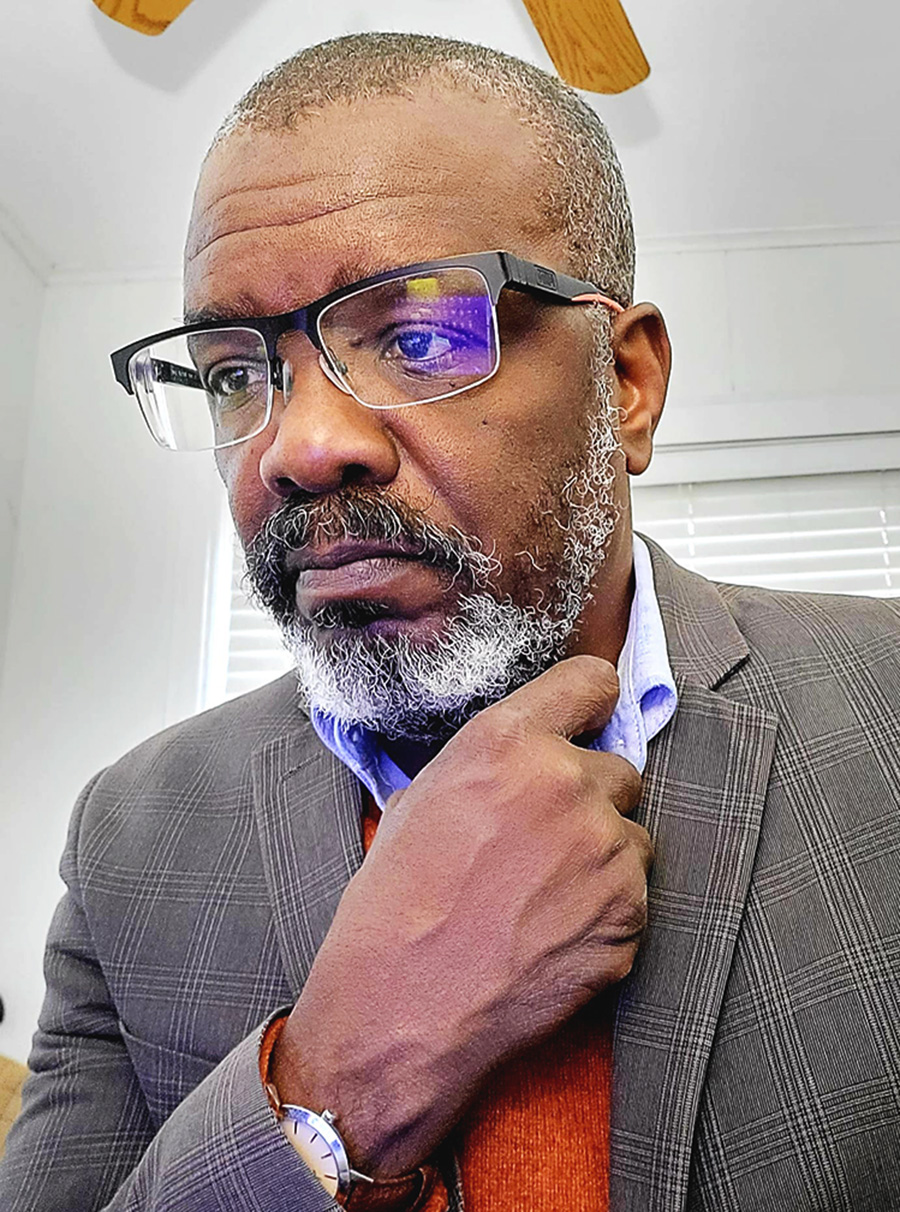

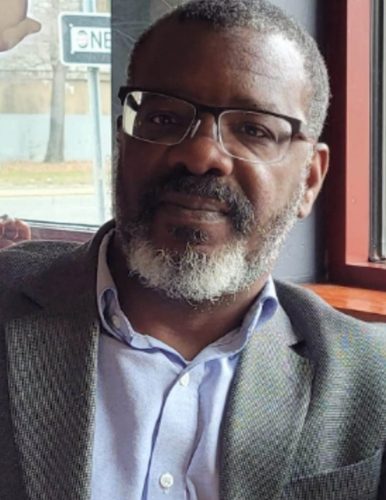

Former educator Berkeley Wendell Semple, 56, a two-time winner of the Guyana Prize for Literature, Poetry category, in 2004 and in 2022, who is now putting together his fifth volume of poems for publication, found inspiration to write during his years of serving the USA in the military during Desert Storm and while stationed at sea.

“Things got a little lonely at sea because we were there for months. In the library on the ship I discovered the poems of St Lucian poet, Derek Walcott, some Guyanese and other Carib-bean writers. Poetry was another life. It intrigued me,” Semple told Stabroek Weekend from his home in Long Island, New York.

Semple, who also writes short stories, said his new book, a historical collection, for which he has finished the first draft, is titled, Imperial Reach.

“It explores some historical events that made Guyana, for better or for worse, what it is today. It goes back to Sir Walter Raleigh and his search for El Dorado. Imperial Reach deals with how the colonial times influenced how we operate, our language, how we discuss things and even how we make love,” he related.

He hopes to publish Imperial Reach by next year, and is looking at Peepal Tree Press as the publisher. The advantage of publishing with Peepal Tree, he said, is that it has an international reach. “I’ll get more backing as a writer, and as well, to advertise. However, poetry is poetry. You are not going to see it on a bestsellers’ list,” he stated.

Semple loves classic writers like Wilson Harris, Martin Carter, Roy Heath, Dr David Dabydeen, Sasenarine Persaud and Harold Bascom.

“I’m pretty versed in their work and I enjoy them. I know Fred D’Aguiar. He’s from Mahaicony. I speak highly of Guyanese writers because they are super writers who share their ideas and support other local writers,” he enthused.

A writer who takes pleasure in writing about the Guyanese landscape, Semple noted that the Guyana landscape and the Guyanese Creole language are not often used in other Guyanese writers’ works.

“Perhaps the reason these young guys don’t write about Guyana is that they are embarrassed about certain aspects of it. Maybe they are embarrassed to use Creole or maybe they think that the people and the language are not worthy subjects for poetry. I think they are perfect subjects. Guyanese culture is new and it will inform the world about who is a Guyanese, what is the Guyana culture and how important we are to the world,” he continued.

“In Wilson Harris’ Palace of the Peacock, the landscape is there. In the fiction, in the stories, the landscape is there, but not in poetry. I wonder why. I write about everything: the mango trees, the cows in the field. You can’t write about Guyana if you can’t describe the place. Martin Carter was a gifted poet. His subject was always Guyana but not his landscape. Ian McDonald writes a lot about Guyana’s landscape.”

The country Guyana that Semple knows, is new. “Most people in the rest of the world don’t know about Guyana or where it is. They mistake Guyana for Ghana, Guinea or a whole lot of other places,” he noted.

Origins

Born in Wismar where his father was a mining operator in the bauxite industry, his family, which was originally from Mahaicony moved back there when he was about 11 years old.

Semple moved to the USA at 14 with his parents. He completed high school in New York, after which he was in the US army for six years. While he was stationed on the battleship USS Missouri during Desert Storm, he took an interest in the writings of Guyanese and Caribbean writers.

“When I came off the ship I started writing. I did a bachelor of arts in English/Creative Writing,” he said. He then obtained a master’s degree in English/Creative Writing from Queen’s College, City University of New York, where he had also done his bachelor’s. He followed up with a master’s degree in Philosophy in Information Science from Long Island University, where he is now working on his dissertation for a PhD in Information Science. His dissertation is on conservation in a digital world.

After teaching for 22 years in the public school system in New York, he worked as an administrator in a New York library for a number of years then left. He returned to the library in June this year.

As a side job, he reviews books for journals. He is currently reviewing Sasenarine Persaud’s new book, Mattress Makers. He is an editor of Caribbean Voice magazine and the annual Caribbean Writer magazine and he writes essays on Caribbean literature for journals.

In his writings, his main subject is Guyana. “All my books are about Guyana; its politics, culture, the people, the environment. A lot of it involves life and the interactions of people and anything that affects people on the coast. I write about the diaspora, but not well and not often,” he said.

When he was a teenager, his parents sent him from the US to Mahaicony during the summer holidays.

Now the father of three children, he sends them to spend their summer holidays in Guyana. He also travels to Guyana twice a year.

The Guyana Prize

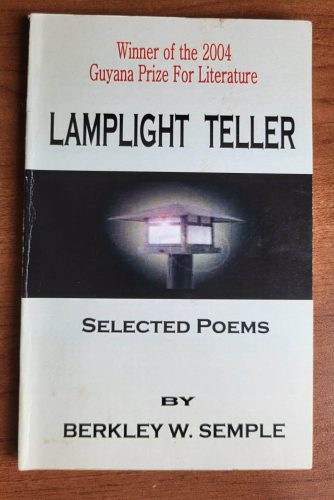

Semple was reading for his master’s degree in English and creative writing, specifically in poetry, when he submitted his first collection of poems for his master’s thesis.

“My professor thought it was really very good. She gave me the names of some publishers and I published,” he recalled. That first book, Lamplight Teller, won the first prize in the poetry category of the Guyana Prize for Literature in 2004. It also won the Caribbean Writers’ Prize, Poetry in 2005. Semple has also won several prizes for individual poems.

“Wherever you live, there is always someone telling a story. On the coast we gathered under the lamplight to listen to someone tell stories, mostly made up tales,” he recalled.

Winning the Guyana Prize for Literature in 2004 encouraged him to continue writing. “It gave me a real sense about how people felt about my poetry,” he said. In 2004 he also met Dr Victor Ramraj, Dr David Dabydeen and Fred D’Aguiar who encouraged him to continue writing.

“I really took it seriously after that. It doesn’t pay the bills. It didn’t pay tuition for school for my little ones when they were growing up. It didn’t feed the family and pay the mortgage, but it is something I love and I do it on a daily basis,” he said. “My working life is generally from nine to five. Then it’s family time. I generally write from midnight to 2 am. That I’ve been able to do it, is remarkable to me because there was so much going on. If I don’t make the time for writing, then it can go away entirely in everyday living. I’m glad I’m persistent in doing both. I had to manage myself well but then I learned that discipline from being in the military.”

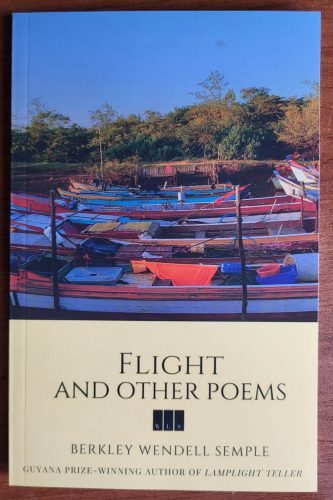

Semple has published four collections of poetry including his most recent, Flight and Other Poems, which won the 2022 Guyana Prize for Literature in Poetry. His second book, the Solo Flyer, and the third, The Central Station, were also shortlisted for the Guyana Prize. His three previous books were published by a small press in California.

“My typical way to get feedback on my poems is to publish most of them in Caribbean journals or magazines before I put them into a collection for a book. Even before I publish, I usually send my work in galley form to writer Petamber Persaud, who I have known for a long time, to review. He usually gives me good pointers and feedback,” he said.

He publishes in the Caribbean Writer, a journal published by the University of the Virgin Islands; Callaloo, the journal of literature, art and culture in the African Diaspora; and Poui, a journal of creative writing published by the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus.

Flight and Other Poems

Flight and Other Poems, his last book which was published by Amazon is 130 pages. “It is big for a poetry book. Over the ten years I collected all of those I’d published in journals and put in one book. I was very happy to win the Guyana Prize with that book because I thought it was my best book. It was much more comprehensive than the others. It sought to encompass all of Guyana, its culture, mythology, politics, the highs and the lows of Guyanese, death and the environment. It is really a kitchen-sink sort of collection to the degree that a great deal of it is wildly varied in discussing the subject matters. I’m very proud of it,” he stated.

Flight in the title is used as a metaphor to mean flights of fantasy, losing a lover or losing someone to death. “So the metaphor is weaved into the poems. I couldn’t omit those personal tragedies that happened during the Covid-19 pandemic. We lost a lot of loved ones. We weren’t allowed to gather, to mourn or to bury our dead properly,” he recalled.

Flight in politics as a metaphor encompassed the intrigue and uncertainty surrounding general elections, he said. “I had some fun with that. Even if a winner is declared, accusations of cheating or stolen elections abound…,” he added. “The kind of animosities between the major ethnic groups or races might be something manufactured and may not be something real or genuine. At Mahaicony, where I am from, I don’t see that kind of rancour between the races as being so obvious or visceral. If you live in a mixed village on the coast it is less so.”

Guyana has a problem with class for sure but Guyana’s politics does not make for good poetry. “The politics make for a kind of sad, sometimes very didactic poetry,” he declared. “I’m not here to teach a lesson but poetry should make people feel, then reflect. Good poetry makes you see familiar things so differently. A really good poem should have a surprise element. I try to do that with Guyana. I try to keep it honest in what I say. I want the reader to feel some of the essential truth. Bad poetry has no surprises. It bores you.

“If you read Coolie Odyssey by David Dabydeen, or Airy Hall by Fred D’Aguiar, you can feel the Guyaneseness and the honesty in the words. Especially Dabydeen in the use of Creole in ‘Slave Song’; you can feel the genuine hurt, pain that the person is going through. You sympathise with the character in the poem. It is important to make the person feel, more than think. Thinking might happen after they feel.”

Semple thinks that Guyana has never been so literary as it is now. He said he was at a reading at Castellani House earlier this year where he met some young writers, “who are incredibly serious. I was shocked at how well read and knowledgeable they are. At their age I didn’t know as much poetry as they know. They are much more schooled and their writing is much more inventive, adventurous and contemporaneous in their approach. The Guyanese poets of my generation were much more formal in their approach to writing. The subject matter of their poetry are things that affect them now. They talk about them in such a forceful way.”

‘Guyaneseness’

Before his family migrated to the USA in April 1982, Semple milked cows with his grandfather in the morning before they drove the cows to the field.

“When I first came here, I dreamt a lot that I was back home with my grandfather. I would wake up heavily disappointed that I was not in Guyana,” he recalled.

There was a time when he was afraid that being away from Guyana he would lose his connection to his ‘Guyaneseness.’

“It is terrifying because if I’m not Guyanese, who am I? Guyanese is my identity even though I have lived here for most of my life. I am not a hamburger eater. I eat what Guyanese cook. So my culture remains intact. I go to Guyana twice a year because it is food for my own thinking and certainly my poetry. The fear of losing contact with my culture, my Creole language, this engagement with Guyana, its people, its essence, its environment, the things I write about, was a terrifying thing. I experienced that when I was much younger. I’m less afraid now. As I grow older the more Guyanese I become,” he said.